THE JOURNEY FROM MAGIC, TO RELIGION AND TO SCIENCE

SYNOPSIS

Throughout history, humanity has grappled with fundamental questions about existence, the purpose of life, and the structure of reality. Human intellectual development has unfolded through four pivotal stages: magic, religion, philosophy, and science.

The first Homo Sapiens evolved in Africa 200,000 years ago during the middle palaeolithic era 300, 000 – 50, 000 BCE. By this time, humans had become incredibly intelligent beings who could not only reflect upon themselves and the world around them but could also reflect upon their existence within the world; in other words, they realised they were the object of their consciousness; they had become self-aware.

To do this, the brain needed to evolve from being a mechanism that experienced sensations and thoughts to becoming the observer of itself. With this level of perception, it was only natural that early man would develop philosophies about the meaning of life and death. The earliest known human burial was in the Middle East c.100, 000 BCE. ‘ but people must have developed philosophical ideas before this date because thinking abstractly and creatively is the outcome of having a sophisticated cerebral cortex.

The topic of exactly when and where philosophy first began to develop is still debated. Still, the most straightforward answer is that it would have started the first time someone asked why they were born and how they were supposed to understand their lives at any time in the distant past.

The term philosophy may apply to a formalised secular or religious system of thought, personal constructs, or communal understanding of beliefs. Still, in each case, the purpose of the system is to develop theories about existence, such as:

What is the purpose in life?

What is the meaning of existence?

Who am I?

What is my nature?

Where do I go when I die?

Picture this: you are one of the human beings living hundreds of thousands of years ago. You're out on the plains of the Serengeti, shooting the breeze with your fellow hunter-gatherers, when one of them asks the group,

“What is death, and where do we go when we die?”

While such questions wouldn’t have gotten definitive answers, their mere existence highlights the extraordinary capacity of humans to seek meaning beyond survival—a trait that continues to define our species

In summary, the roots of philosophical thought trace back to magic—humanity’s earliest attempt to impose order on chaos.

THE THEORY OF MIND (TOM).

The ancestral plains were perilous landscapes where hunters who weren't vigilant faced the constant threat of being taken down by the environment—essentially, it was a matter of “kill or be killed.” In such hostile conditions, survival was only possible because humans developed the ability to recognise that other beings—whether predator or prey —possessed independent existences and had minds of their own. This cognitive capacity, which psychologists call the "Theory of Mind" (TOM), meant humans could see the intentions in others.

TOM allowed humans to recognise that the actions and behaviours of other beings were purposeful, which played a crucial role in making life-saving decisions. Early man had to quickly assess the intentions of potential predators, asking themselves questions like, 'Is that movement in the meadow a snake? Snakes bite—better run.” The capacity to perceive 'agency' in others was vital for survival in various contexts, such as mating—' Does that person want to fornicate with me, kill me, or ambush me?

However, the exact cognitive mechanisms that allowed humans to interpret the intentions and actions of living beings also enabled them to attribute purpose and intentionality to non-living entities, such as geographical features and celestial bodies. Without accumulated understanding or shared explanations to interpret natural phenomena, early humans used these mental shortcuts to make sense of their world. For example, they might assume these forces acted with intention or purpose without knowing why the sun rose or rivers flowed. This approach helped them create a framework for understanding their environment when no other explanations were available.

In addition to helping humans make rational decisions, TOM may have planted the seeds for religious thought. While the Theory of Mind initially evolved as a survival tool, allowing humans to navigate their environment by attributing intentions to the living and the tangible, it also laid the foundation for something far more transcendent: the leap into abstract belief. Animism, with its roots in the physical world, offered a way to see agency in rivers, mountains, and stars. Yet ToM did not stop at the material—it enabled humans to imagine beings untethered from the natural world, capable of shaping existence from realms unseen.

This ability to conceive of entirely abstract forces, such as gods, reflects a profound shift in cognition—one where the boundaries of reality dissolved into limitless possibility. It is this cognitive leap, bridging the physical and the immaterial, a uniquely human capacity to craft meaning in the void and transform the unknowable into narratives of divine purpose.

As a result, some scientists refer to TOM as the "god faculty. “

THE ORIGINS OF COLLECTIVE LEARNING

"If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

Because early man lived in the Paleolithic age, he couldn’t access education and the insight of other people’s wisdom because it didn’t exist yet. The knowledge base of the twenty-first century didn’t happen suddenly; it took a couple of hundred thousand years to accumulate. “Standing on the shoulders of giants” is a metaphor that means using the understanding gained by major thinkers born before you to make intellectual progress. Issac Newton exemplified this perfectly by explaining that his ideas didn’t come from him alone. He said that he relied on the ideas of those who had already made significant contributions to scientific knowledge. As a result, Newton didn’t regard himself as a genius.

In short, collective learning is the uniquely human ability to share, preserve, and build upon knowledge over time. People rely on collective learning when reading a book, attending school, or watching a documentary. The history of science is the story of collective learning. Historians piece evidence across time and continents and show how our collective knowledge developed.

The middle Paleolithic era was the very start of this collective learning journey. At the beginning of man’s existence, there were no social constructs, objective truths about existence, and no scholars to learn from. Therefore, anything was possible, and all early theories were equal. Moreover, living in small, nomadic groups meant little interaction, so the spread of any idea was greatly restricted.

Unsurprisingly, the people who lived during this period would have had primitive and mystical ideas about their existence and the objects that inhabited their world. “….so that enormous ball of yellow in the sky” could have been anything: a god, another world, an “all-seeing eye”, or even an evil force. The people back then would have been perplexed about the behaviour of celestial bodies like the sun.

“Why was it so luminous some days but hid behind fluffy white things on other days, disappeared altogether - taking all light and warmth with it? Was it displeased? Did something happen to make it go away? Did it watch them? Would they go to it when they died?”

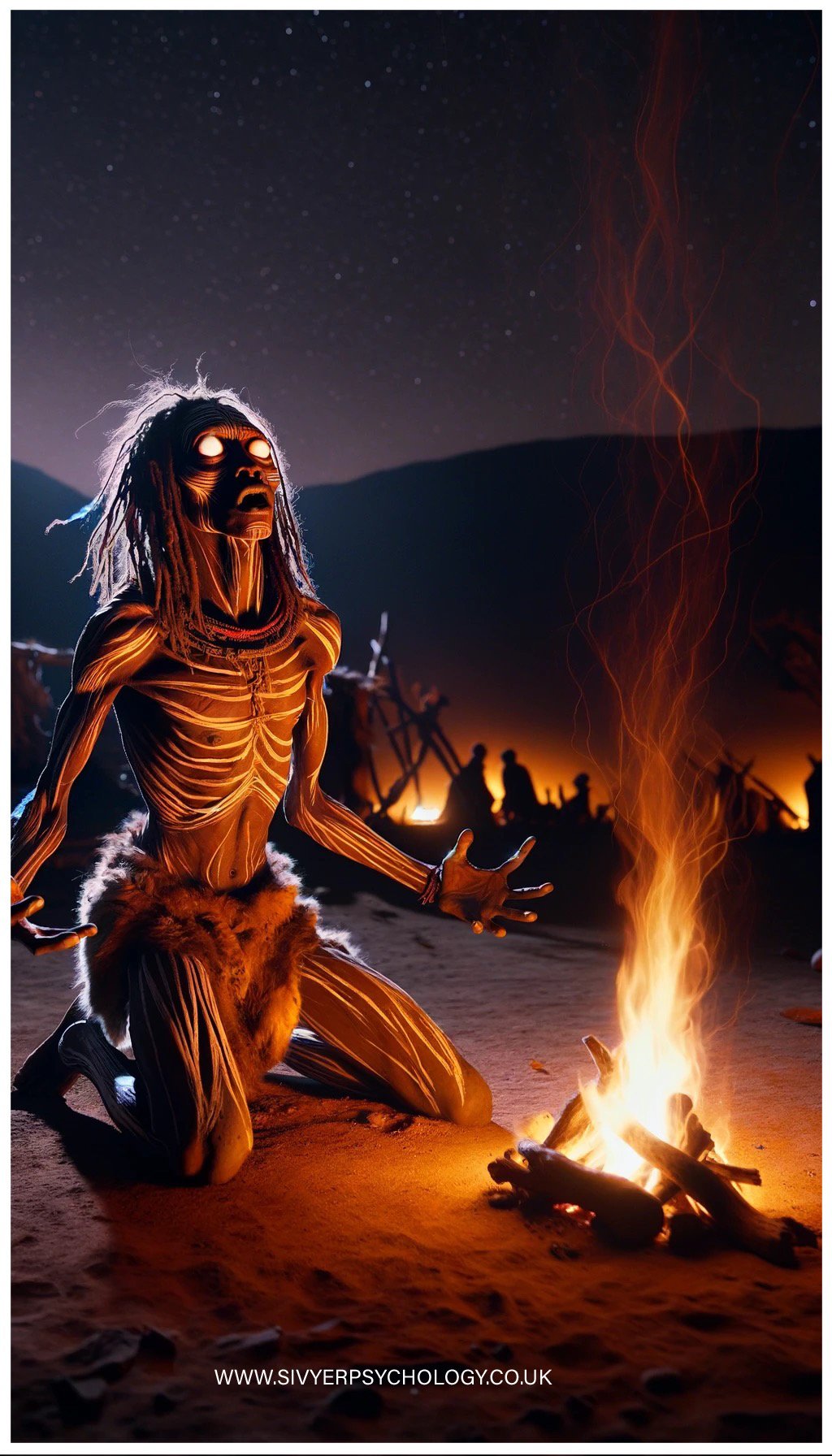

THE BIRTH OF THEORIES BASED ON MAGIC

In the early phases of human evolution, early humans likely harboured a deep fear of natural phenomena such as storms, droughts, and floods, events whose power seemed overwhelming and whose impact was often devastating. Without distinguishing between the living and the inanimate, they projected thoughts, emotions, and intentions onto their surroundings. Rivers flowed with purpose; mountains stood as sentinels, and celestial bodies danced across the heavens with mysterious intent. To them, these forces were not indifferent; they were alive, imbued with spirits or governed by unseen deities. Catastrophes were seen as the wrath of malevolent beings dwelling in the earth, rivers, or sky. At the same time, the movements of the sun and stars were interpreted as the purposeful actions of powerful gods.

In this world, animism emerged—a belief system where everything in nature had a soul, and humans could interact with these spirits to influence their lives.

In this world, animism emerged—a belief system where everything in nature had a soul, and humans could interact with these spirits to influence their lives.

While animism thrived as a collective belief system, it struggled to evolve alongside the increasing complexity of human societies. Its loosely defined rituals and explanations were tied to localised phenomena and lacked the organisational structure needed to address broader societal challenges. As communities expanded and interconnected, animism gradually gave way to more formalised systems, like totemism and shamanism, which offered shared rituals, moral frameworks, and a stronger sense of communal identity. This evolution wasn’t about abandoning animism entirely but adapting belief systems to meet the demands of a growing and more diverse population.

Shamanism answered this call, with shamans serving as intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds, wielding influence through rituals that linked the visible and invisible. But as societies grew and became more complex, humans sought more profound symbols to bind them together—not just to the spirit world, but to one another.

Totemism arose as a natural extension of this desire for connection. It introduced the idea of clans or tribes adopting specific animals or natural symbols as sacred emblems of their collective identity. A totem was more than a symbol; it was a bridge between the human and natural worlds, embodying the qualities and power of the chosen animal or force. This practice aligned communities with the rhythms of nature while reinforcing social bonds through shared reverence for their totems.

EDWARD BURNETT TYLOR (1832–1917) proposed that magic was the earliest form of belief from which all religions evolved. He viewed magic as a framework that introduced the concept of the soul and the animation of inanimate objects, serving as the foundation for subsequent world religions, which adapted and expanded on these basic ideas. Tylor envisioned human development as a progression from magic to religion and ultimately to science, each step representing an increasingly rational and institutionalised approach.

Tylor also theorised that humanity advanced through three distinct stages. The first stage, "savagery," was characterised by hunting and gathering practices. The second stage, "barbarism," was marked by the advent of pastoralism and agriculture. Finally, the "civilisation" stage emerged, distinguished by industrialism. Tylor sought to map all forms of religious worship onto an evolutionary scale, demonstrating how beliefs evolved from simple animistic ideas—where spirits were believed to animate the natural world—to what he considered more complex religious systems, such as Hinduism.

Although these early belief systems might seem primitive from a modern perspective, they were built upon rational frameworks that made sense within their time's cultural and historical contexts. By attributing agency to the forces of nature, early humans created a coherent way to interpret and respond to the unpredictability of their environment.

Over time, rituals became more elaborate, reflecting early societies' cognitive and social advancements. As humans formed more significant and complex communities, the symbolic frameworks of magical ideas, while substantial, began to show their limitations. Rooted in nature and community identity, these systems struggled to address life’s more profound mysteries or provide the unifying structures required for increasingly interconnected societies. This shift paved the way for formalised religion, where intangible forces and moral codes offered a more comprehensive framework for existential and social needs."

THE TRANSITION FROM MAGIC TO RELIGION

Without collective knowledge, magic served as an unformalised framework for explaining existence. While effective for addressing small-scale concerns, such as invoking spirits for hunting success, magic struggled to account for more significant phenomena like droughts or natural disasters. For instance, rituals aimed at summoning rain might fail repeatedly, challenging the credibility of these practices even among early societies. These inconsistencies revealed the limitations of attributing agency to inanimate forces, paving the way for religion, which introduced more structured and enduring belief systems.

Religion succeeded where magic faltered by addressing practical concerns and profound existential questions. By embedding moral codes and shared narratives into collective worship, religion provided a resilient framework that unified communities and sustained their cohesion through times of uncertainty."

THE JOURNEY TO RELIGION

As magical ideas began to fail under scrutiny, they gave rise to formalised religion—a more enduring and structured system of thought. Both magic and religion sought to address life’s uncertainties, but religion diverged by focusing on intangible forces, like sky gods, beyond empirical testing. This shift gave religion a unique resilience; unlike magic, it offered meaning that could withstand direct refutation while providing a unifying framework for early societies. Religion allowed humans to tackle profound existential questions, foster moral codes, and strengthen societal cohesion through shared rituals and collective narratives.

SKY GODS

The celestial bodies—the sun, moon, and stars—fascinated early humans. Unlike stationary objects like rivers or mountains, these bodies moved with deliberate and mysterious rhythms, sparking the belief that they might possess intentionality. The deliberate and mysterious rhythms of celestial bodies led early humans to attribute intentionality to these forces, personifying them as powerful gods.

As these unseen forces took on identities, humans began to anthropomorphise them, assigning human traits such as emotions, desires, and intentions. This cognitive leap made these abstract deities more relatable, transforming them from distant, unknowable forces into figures with whom people could interact. This anthropomorphic transformation allowed humans to engage with these celestial entities through offerings and appeals, shaping rituals that linked the human and divine worlds. Over time, these deities became more than explanations for natural phenomena; they were woven into the fabric of daily life and social systems, reflecting the hopes, fears, and moral frameworks of the communities that worshipped them.

This process also allowed for a more personal and relatable connection between humans and the divine. As societies grew more complex, anthropomorphic deities began reflecting human hierarchies. Kings and rulers often aligned themselves with these gods, claiming divine authority to legitimise their power. This development intertwined religion with governance, using both as tools to maintain social order. Gods were no longer just abstract forces—they became powerful entities, much like human rulers, who could be pleased, angered, or appealed to. For example, Early Mesopotamian and Egyptian gods were depicted as governing the natural world, embodying its forces and serving as moral exemplars.

EVOLUTION OF RELIGIOUS THOUGHT

From a psychological perspective, this shift was rooted in humanity’s evolving cognitive abilities. Without knowledge of biology, early humans likely viewed the mind as something abstract, distinct from the body. The subjective nature of identity, emotions, and thought, which seemed too profound to be physical, encouraged the belief in a soul—a divine essence that animated life. Religion capitalised on this intuitive sense to explain not just individual consciousness but the nature of existence itself.

Philosophically, the transition from magic to religion marked an intellectual leap. Magic, focused on immediate cause-and-effect thinking, led to religion’s exploration of more profound questions: Why do we exist? What happens after death? These existential questions shifted humanity’s focus from practical outcomes to the search for purpose, laying the foundation for future philosophical inquiry. Religion’s shared stories and rituals amplified collective learning, transforming isolated beliefs into expansive cultural frameworks. By unifying communities around shared myths, religion became a cornerstone of societal development, fostering cooperation and trust.

Symbolic thinking was pivotal, allowing humans to link observable phenomena—like storms or celestial movements—with imagined forces. Language amplified this process, enabling them to share and solidify abstract ideas within their communities. For instance, early cave art depicting animals and hunting scenes may have symbolised attempts to invoke spiritual favour or represent proto-religious practices tied to survival and the environment. These symbolic connections formed the basis for early rituals, where humans sought to appease or align with these imagined forces through offerings, ceremonies, or artistic representations. Over time, these imagined forces became central to religious thought, transforming individual interpretations into collective beliefs.

This shift was gradual and shaped by cultural, environmental, and social factors. The movement from attributing intention to the physical world to imagining powerful, unseen beings represented a profound shift in how humans understood themselves and the universe.

THE EMERGENCE OF MORAL FRAMEWORKS

Religion did more than unite societies—it revolutionised the concept of morality by tying it to something eternal, something beyond human control: divine judgment. For the first time, actions were framed as right or wrong and cosmic transactions with eternal consequences. Morality became sacred, turning the everyday decisions of individuals into matters of universal significance. This was a game-changer.

Unlike the pragmatic rituals of magic, which sought immediate results, religious moral frameworks introduced an audacious claim: humans were being watched. Higher powers were passive observers and active judges, rewarding virtue and punishing vice. This idea made morality an omnipresent force. It wasn’t enough to appear suitable; true piety demanded inner discipline. Even thoughts could now be weighed on divine scales—a terrifying prospect for early societies and a powerful tool for maintaining order.

Take the Ten Commandments, for example. These weren’t merely laws but declarations of a higher authority that transcended kings and chiefs. “Thou shalt not kill” didn’t just prevent murder—it reminded individuals that every life belonged to God, not to them. Similarly, Hinduism's Dharma concept demanded adherence to societal roles and alignment with a cosmic order. To fail one’s duty was to disrupt the universe itself—a chilling responsibility.

This shift wasn’t just moral; it was deeply psychological. Religion planted guilt, shame, and redemption in the human psyche by tying ethics to eternal consequences. Individuals weren’t just accountable to their tribes or rulers but to the cosmos. This gave religion unparalleled power: it wasn’t merely regulating behaviour but colonising the inner world of thoughts and emotions. It turned morality into an intimate, inescapable reality.

Leaders quickly saw the potential. If morality was divine, rulers aligned with the gods could claim a terrifying authority: defying them was to defy heaven itself. In ancient Egypt, pharaohs were seen as living gods, embodying ma’at—cosmic balance. To question their rule wasn’t just rebellion; it was blasphemy. Religion’s moral frameworks weren’t just tools for cohesion—they became weapons of control, wielded with divine endorsement.

But this wasn’t all darkness. These frameworks also offered hope. For the first time, individuals were given a reason to act selflessly, to see their small lives as part of something grand. The promise of divine justice meant that even the oppressed could dream of ultimate fairness, that the wrongs of this world might be righted in the next. This duality—fear and hope, judgment and redemption—ensured that religion didn’t just survive but thrived, embedding itself in the fabric of human society and shaping its moral consciousness for millennia.

EARLY FORMALISED RELIGIONS: EXPLORING EXISTENCE AND THE DIVINE

As human societies grew more sophisticated, so did their understanding of existence. Religion evolved from a way to appease unseen forces into a framework for grappling with profound existential questions: Why are we here? What happens after death? What is the nature of the universe? Formalised religions emerged as humanity’s bold attempt to impose order on chaos, offering explanations and meaning.

GREEK POLYTHEISM: HUMANISING THE DIVINE

The Greek pantheon is a testament to the human tendency to see the divine as a reflection of themselves. Gods like Zeus and Athena weren’t paragons of virtue—they were deeply flawed, jealous, and vengeful, embodying the full spectrum of human emotions and behaviours. Yet, these imperfections made them relatable, providing a lens through which mortals could understand their own lives.

Greek mythology didn’t shy away from life’s darker truths. Fate loomed large, often depicted as an inescapable force even the gods couldn’t defy. This paradox—powerful gods subject to even greater cosmic laws—sparked the philosophical inquiry. Thinkers like Socrates and Plato challenged the myths, asking whether morality and justice were divine or if they existed as universal principles independent of the gods. Greek religion thus paved the way for the earliest debates on ethics, free will, and human purpose.

HINDUISM: COSMIC ORDER AND REINCARNATION

Hinduism offered a radically different perspective on existence. Rather than focusing on the whims of anthropomorphic gods, it emphasised cosmic interconnectedness and the eternal cycle of creation and destruction. Concepts like Atman (the self) and Brahman (ultimate reality) invited believers to look inward, seeing themselves as distinct and inseparably linked to the universe.

The doctrine of karma tied every action to a consequence, creating a moral system that extended beyond a single lifetime. Rebirth wasn’t punishment or reward but a reflection of one’s choices, fostering introspection and accountability. Moksha—the ultimate liberation from this cycle—offered a transcendent solution to life’s most significant existential question: how to escape suffering and achieve unity with the divine. In doing so, Hinduism didn’t just explain existence—it offered a roadmap to transcend it.

EGYPTIAN RELIGION: LIFE, DEATH, AND BALANCE

For the ancient Egyptians, life and death were two sides of the same coin, bound by the concept of ma’at—cosmic balance. Deities like Ra and Osiris represented natural forces and the eternal cycles of life, death, and rebirth. This belief wasn’t merely theoretical; it was convenient, shaping everything from governance to burial practices.

The pharaoh, seen as a living god, was the enforcer of ma’at. His rule wasn’t just political but cosmic, maintaining harmony between humans and the divine. Death, far from being an end, was a transition to a carefully constructed afterlife. The Book of the Dead, with its intricate instructions for navigating the underworld, reflected a religion obsessed with moral accountability. The deceased's heart was weighed against the feather of ma’at—a literal measure of their virtue. Egyptian religion fused morality, governance, and metaphysics into a single, all-encompassing worldview.

MONOTHEISM: ONE GOD, ONE TRUTH

The leap to monotheism marked a seismic shift in humanity’s understanding of the divine. Traditions like Judaism, Christianity, and Islam replaced many gods with a single, omnipotent deity—an unchanging source of truth, justice, and moral law. This simplification wasn’t just theological—it was revolutionary. It introduced the idea of universal morality, transcending cultural and geographic boundaries.

Judaism’s covenant with God framed morality as a sacred contract, with divine commandments guiding every aspect of life. Christianity expanded this framework with the promise of salvation and grace, offering hope for this life and eternity. Islam unified spiritual and temporal concerns, presenting a submission to Allah as a personal duty and a foundation for societal order.

Monotheism also reframed existential questions. Free will, justice, and suffering took on new dimensions under the watchful eye of a singular deity. If God was all-powerful and all-loving, why did evil exist? These questions pushed human thought into the realm of philosophy and theology, debates that continue to shape the modern world. Monotheism didn’t just answer questions—it created new ones, driving humanity’s endless quest for understanding.

PHILOSOPHICAL AND EXISTENTIAL INSIGHTS

“Religion was not a passive acceptance of the unknown but an active engagement, a search for coherence in chaos.”

Early religions were not mere attempts to explain the world—they were audacious systems that reshaped how humans understood existence and their place in it. Humanity confronted profound existential questions for the first time: Why are we here? What is the purpose of suffering? What lies beyond death? These religions didn’t just offer answers; they wove individual lives into a larger cosmic narrative, transforming chaos into meaning.

What made these systems transformative wasn’t just their stories but their ability to unify. By linking human experience with divine intention, early religions provided coherence in a world of uncertainty, turning fear into understanding and isolation into community. These frameworks inspired accountability and hope, elevating individual actions to cosmic significance.

Beyond unity, early religions laid the groundwork for more formalised philosophies. They dared to ask questions that transcended mere survival: What is justice? How can flawed humans aspire to divine ideals? These questions spurred intellectual traditions that would echo across centuries, bridging the realms of myth and reason.

In grappling with life’s mysteries, early religions didn’t just reflect human experience—they shaped it. They offered a vision of human existence as purposeful and interconnected, laying the foundation for civilisation. By aligning the mundane with the divine, they forged systems that explained the world and inspired humanity to strive for something greater.

FROM RELIGION TO PHILOSOPHY: THE EVOLUTION OF THOUGHT

As societies became more complex, so did the scrutiny of inherited beliefs. Religion, which had long provided moral guidance and unified communities, faced questions that exposed its vulnerabilities. Epicurus’s Problem of Evil epitomised this shift, challenging the coherence of a benevolent, omnipotent deity in a world rife with suffering. His words were not merely a critique of religion but a rallying cry for reason, inviting humanity to confront its deepest assumptions.

Philosophy emerged as an organised way of examining life’s uncertainties through reason and logic, challenging and complementing religious thought. Unlike religious frameworks, which often relied on divine revelation or tradition, philosophy sought to uncover truths through structured methods such as critical reasoning, debate, and observation. Socrates famously questioned whether something is good because the gods command it, or if the gods command it because it is good—a dilemma that moved morality away from divine fiat toward rational principles.

This shift was not about rejecting religion but broadening its scope. Philosophers sought to refine religion's answers, investigating whether its teachings were universal truths or culturally specific constructs. This interplay between faith and reason laid the groundwork for moral and existential frameworks that transcended the gods.

COLLECTIVE LEARNING AND THE RISE OF CRITICAL THOUGHT

As human societies developed and collective learning advanced, religious narratives came under greater scrutiny. The coherence of divine ideas and their cultural specificity were critically examined, reshaping humanity’s understanding of morality, justice, and existence.

In his epic poem On the Nature of Things, Lucretius dismissed the gods entirely, attributing natural phenomena to physical laws and atomic interactions. His materialist perspective replaced supernatural causality with reason and observation, challenging divine intervention. Meanwhile, Aristotle integrated religious questions into systematic thought, grounding ideas like telos—the intrinsic purpose of all things—in observable truths. By blending empirical inquiry with metaphysical exploration, Aristotle demonstrated how philosophy could refine religious ideas rather than reject them outright.

At the same time, bold challenges to orthodoxy arose. Baruch Spinoza equated God with nature, presenting divinity as an impersonal, universal force. Immanuel Kant argued that morality could exist independently of divine authority, further distancing philosophy from theological roots. These thinkers explored profound religious questions but sought to answer them with reason, critical thought, and universal principles.

FROM RELIGION TO PHILOSOPHY: A SYSTEMATIC TRANSFORMATION

The rise of philosophy marked a disciplined move from reliance on religious authority to logical and systematic inquiry. Philosophers questioned whether morality, justice, and truth could exist without divine oversight. This wasn’t about disproving religion but expanding its scope—challenging assumptions and seeking principles that could withstand critical scrutiny.

Plato’s ideal forms posited that justice and morality were universal truths beyond gods and mortals. Aristotle’s empirical approach argued that the natural world could be understood through observation and logical reasoning. These ideas created a framework for intellectual exploration that transformed human thought and set the stage for science.

CHALLENGING RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS

The systematic nature of philosophy emboldened thinkers to question the coherence of religious narratives. Greek atomists like Democritus introduced the idea of a universe governed by natural laws rather than divine will, proposing that all matter consisted of indivisible particles moving in a void. This materialistic view directly opposed the religious portrayal of an ordered cosmos controlled by gods.

Philosophers like Xenophanes revealed how divine concepts often reflected human needs and cultural biases by critiquing anthropomorphic gods and interventionist narratives. These challenges reshaped religious thought, encouraging it to evolve and integrate reason.

SYSTEMATIC THINKING AND THE QUEST FOR TRUTH

Philosophy’s reliance on reason, logic, and evidence introduced a disciplined approach to existential inquiry. This method allowed thinkers to scrutinise inconsistencies in religious narratives while preserving the depth of their questions. By shifting the focus from divine will to universal principles, philosophy reshaped humanity’s understanding of morality, justice, and truth, transforming faith-based concerns into enduring frameworks of thought.

REIMAGINING EXISTENCE

The transition from religion to philosophy marked a leap in human thought, introducing more structured ways of addressing existential questions. While religion relied on faith, philosophy employed reason to explore existence systematically. However, philosophy’s speculative nature revealed its limits—it could ask profound questions about free will, evil, and the divine but lacked empirical tools to test its ideas.

This limitation paved the way for the scientific revolution. Philosophy’s frameworks bridged the gap between faith and science, transforming humanity’s quest for knowledge into a continuous journey of discovery.

FROM PHILOSOPHY TO SCIENCE: A REVOLUTION OF KNOWLEDGE

Stephen Hawking famously declared that "philosophy is dead," asserting that it "has not kept up with modern scientific developments, particularly physics." According to Hawking, scientists are now the "bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge." This shift from speculative philosophy to empirical science reflects a profound evolution in how humanity understands the universe—a journey driven by observation, experimentation, and ever-advancing tools. Central to this transformation was the accumulation and refinement of collective knowledge, which dismantled ancient assumptions and reshaped the boundaries of human understanding.

THE SHIFT TO EMPIRICISM

The hallmark of scientific thinking lies in empiricism—knowledge derived from observation, measurement, and evidence rather than abstract reasoning alone. Philosophy posed critical questions about existence, but empiricism demanded answers that could be tested and verified. This wasn’t just a theoretical shift; it transformed how humans engaged with reality.

Empiricism was more than a method; it was a revelation. Revolutionary tools like telescopes, microscopes, and particle accelerators did more than extend human senses—they opened windows to previously unimaginable worlds. These instruments dismantled assumptions, revealing truths that reshaped humanity’s understanding of itself and its place in the cosmos. Philosophers-turned-scientists no longer relied on conjecture but ventured into realms where reality could be observed, measured, and tested. The systematic application of empiricism became a cornerstone of collective learning, enabling humanity to build on past discoveries rather than starting anew with each generation.

THE HELIOCENTRIC REVOLUTION AND GALILEO’S TELESCOPE

The heliocentric theory fundamentally reshaped humanity’s perception of the cosmos. Nicolaus Copernicus dared to propose that Earth was not the universe’s centre, but Galileo Galilei’s telescope brought this radical idea into focus. By observing Jupiter’s moons and the imperfections on planetary surfaces, Galileo overturned Aristotelian views of perfect celestial spheres and shattered the comforting notion of humanity’s centrality in the cosmos.

This shift was more than astronomical; it was existential. For the first time, the heavens could be studied as tangible phenomena governed by observable laws. Galileo’s discoveries marked the beginning of a new era where knowledge had to confront evidence to endure. His work inspired a generation of thinkers who extended his methods to explore everything from planetary orbits to the mechanics of life on Earth.

THE BIG BANG: A NEW COSMIC ORIGIN STORY

Few scientific breakthroughs evoke as much wonder as the Big Bang Theory. In the 20th century, Edwin Hubble’s observations of galaxies receding from one another revealed that the universe is expanding—a discovery that fundamentally altered humanity’s understanding of cosmic origins. Supported by the redshift of light and the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation, the Big Bang Theory provided a breathtaking narrative: a universe born from a singular point, expanding and evolving into the galaxies, stars, and planets we see today.

This was not merely a theory but a paradigm shift rooted in evidence that allowed humanity to peer into the universe’s infancy. Tools like space telescopes have since enabled us to look billions of years into the past, mapping the evolution of cosmic structures. Unlike religious origin stories, the Big Bang narrative is continually refined as new evidence emerges, offering a dynamic and awe-inspiring account of the cosmos.

DARWIN, DNA, AND THE CODE OF LIFE

Empiricism revolutionised biology as profoundly as it did cosmology. Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection revealed that life’s diversity was not the result of divine intervention but adaptive processes observable in nature. Darwin’s meticulous study of Galápagos finches and the fossil record provided a naturalistic explanation for life’s complexity, reshaping humanity’s understanding of its origins.

The discovery of DNA in the mid-20th century deepened this revolution, unveiling the molecular code that underpins heredity, development, and evolution. Sequencing the human genome revealed life’s intricate building blocks, while tools like CRISPR now allow us to edit these sequences, opening unprecedented possibilities in medicine and biotechnology. These breakthroughs illuminate the elegance of life’s mechanisms while raising profound ethical questions: How far should humanity go in reshaping its biological destiny?

RELATIVITY, QUANTUM MECHANICS, AND MODERN TOOLS

Physics, too, has expanded the boundaries of human understanding. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity transformed perceptions of time, space, and gravity, showing that they are not absolutes but dynamic entities shaped by massive objects. His famous equation, E=mc2E=mc^2E=mc2, revealed the interchangeability of mass and energy, laying the groundwork for technologies that would reshape the modern world.

At the quantum level, reality grows even stranger. Quantum mechanics revealed a world of probabilities, where particles can exist in multiple states simultaneously and influence one another across vast distances. These discoveries defy classical logic yet offer profound insights into the universe’s underlying structure.

Modern tools like particle accelerators have made these revelations possible. The Higgs boson discovery at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider demonstrated the mechanisms that give particles mass. At the same time, functional imaging technologies like fMRI have unveiled the workings of the human brain, shedding light on consciousness, memory, and decision-making. These tools continue to redefine the limits of what humanity can know and understand.

BENJAMIN LIBET AND THE ILLUSION OF FREE WILL

In neuroscience, Benjamin Libet’s experiments challenged the deeply held belief in free will. His findings that brain activity precedes conscious decision-making suggest that our sense of agency may be an illusion—a product of the brain rationalising actions already initiated subconsciously. These discoveries unsettle traditional notions of morality and responsibility, illustrating how empirical inquiry can upend even the most entrenched philosophical ideas.

MODERN FRONTIERS: ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND THE DIGITAL AGE

The digital revolution has brought humanity to the brink of uncharted territories. Artificial intelligence now performs tasks once thought exclusive to human creativity, from composing music to making complex decisions. But these advancements also raise existential questions: Can machines ever possess consciousness? Could they surpass human intelligence, and if so, what does that mean for human identity and agency?

Equally provocative is simulation theory—the hypothesis that our reality may be an artificial construct created by advanced intelligence. Though speculative, it challenges humanity to reconsider the nature of existence, echoing the age-old search for meaning in a scientifically informed context.

THE LEGACY OF SCIENCE: A NEW DAWN OF UNDERSTANDING

Science has achieved what philosophy and religion could only dream of—it has pierced the veil of the unknown, transforming questions of speculation into evidence-based understanding. Establishing empiricism as the cornerstone of inquiry has shown humanity how to illuminate the darkness of uncertainty with the light of observation and proof.

This legacy is about uncovering answers and redefining how we ask questions. Science has demonstrated the power of objectivity, teaching us to discard biases and test assumptions against the weight of evidence. It has allowed humanity to move beyond dogma, to calculate probabilities, and distinguish between what can be proven and what cannot.

The transition from reason to empiricism represents a monumental leap in human understanding. For centuries, philosophical reasoning was akin to wandering in the dark, crafting theories without seeing the terrain. With the advent of tools that revealed the unseen—telescopes, microscopes, particle accelerators—the landscape of reality emerged.

Science has dismantled humanity’s most cherished illusions, from the heliocentric worldview to the deterministic simplicity of Newtonian physics. It has laid bare the universe’s complexity, from the intricate machinery of life encoded in DNA to the quantum strangeness that governs the subatomic world. It has shown us that understanding the universe is not about affirming ancient stories but about embracing ever-changing truths that challenge what we think we know.

This is the true revolution of science: not its answers but its method. Science has reshaped our conception of existence by revealing the mechanisms underpinning reality. The mysteries that once inspired awe and fear have been replaced by questions that inspire wonder and investigation. Yet even as science progresses, it does not end the human quest for meaning; instead, it equips us with the tools to ask ever-deeper questions, leaving no corner of the cosmos or consciousness unexplored.

THE INESCAPABLE NEED FOR BELIEF

Despite centuries of intellectual progress, science's answers often fail to satisfy humanity’s most profound existential needs. Scientific truths—though powerful—are impersonal, reducing existence to mechanisms and probabilities. This bleak clarity can leave us searching for meaning beyond what science can measure. And so, even in an age of reason, belief persists—not as a failure of intellect but as an inherent part of being human.

Our brains are wired for wonder. Studies reveal that activating regions like the amygdala can evoke spiritual experiences, suggesting that belief in higher powers or a divine order may be biologically ingrained. This neurological inclination doesn’t diminish belief’s significance; it underscores how deeply intertwined it is with our nature. The persistence of religion and magical thinking is not a regression but a testament to the enduring power of these narratives to provide meaning, hope, and emotional sustenance.

Science has illuminated much of the unknown, but it has not eradicated humanity’s need for stories that speak to the soul. Perhaps this is not a failing of science or religion but a reflection of a universal truth: that humans, forever conscious of their mortality, will always seek more than what is visible. The journey through magic, religion, philosophy, and science has not replaced one with the other—it has shown us that the search for meaning is infinite and that answers, no matter how compelling, will never silence the questions that define us.

FROM MAGIC, RELIGION, PHILOSOPHY TO SCIENCE: A COMPREHENSIVE TIMELINE

This timeline traces humanity’s intellectual journey from magical beliefs to philosophical reasoning, organised religions, and the rise of scientific understanding, highlighting key developments and figures that have shaped our worldview.

100,000 - 50,000 YEARS AGO: MAGIC AND SPIRITUALITY

EARLY BELIEF SYSTEMS

Animism: Early humans saw spirits and consciousness in nature. This worldview, often called animistic thinking, was a practical attempt to make sense of life-threatening phenomena, such as storms or predator attacks.

Shamanism: Shamans emerged as intermediaries between humans and the spirit world, performing rituals for healing and guidance.

Totemism: Humans developed symbolic relationships with animals and plants, seeing them as protectors or ancestors.

KEY EVENTS

Ritual burials in places like Qafzeh Cave (c. 100,000 BCE) suggest early concepts of an afterlife.

Art like the Lascaux Cave Paintings (c. 40,000 BCE) points to abstract thinking and the roots of storytelling.

12,000 - 5,000 YEARS AGO: AGRICULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NATURE WORSHIP

THE RISE OF AGRICULTURE

The Neolithic Revolution transformed societies from nomadic to sedentary, giving rise to fertility cults and seasonal rituals.

Göbekli Tepe (c. 9600 BCE) is the earliest temple, showcasing organised spiritual practices.

EARLY GODS

Nature worship evolved into polytheism. Inanna (Mesopotamia), Ra (Egypt), and Marduk (Babylon) were early deities representing fertility, sun, and cosmic order.

3,300 YEARS AGO: MAGIC AND RELIGION MERGE

MAGIC-INFUSED RELIGION

Practices like Egyptian rituals combined magic and religion with spells to protect the dead in the afterlife (e.g., the Book of the Dead).

Judaism (1312 BCE): Introduced monotheism and ethical codes with the covenant between Moses and Yahweh.

2,500 YEARS AGO: THE RISE OF PHILOSOPHY

GREEK NATURAL PHILOSOPHERS

Thales (c. 624-546 BCE): Believed water was the fundamental substance of the universe.

Democritus (c. 460-370 BCE): Proposed atomic theory, challenging supernatural explanations of nature.

BUDDHA AND EXISTENTIAL QUESTIONS

Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) (c. 563–483 BCE): Questioned human suffering and taught the path to enlightenment through the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path.

ZOROASTRIANISM

Zoroaster introduced ideas of cosmic dualism—good versus evil—and a moral afterlife, influencing Abrahamic religions.

THE GREEK CLASSICS

Socrates: Promoted ethics and the examined life (“The unexamined life is not worth living”).

Plato: Explored metaphysical ideals in The Republic, introducing concepts of justice and the soul.

Aristotle: Systematised logic, ethics, and empirical observation in works like Metaphysics.

2,000 - 1,500 YEARS AGO: RELIGIOUS CONSOLIDATION

CHRISTIANITY

Jesus of Nazareth’s teachings on love and redemption became the foundation for Christianity.

The Council of Nicaea (325 CE) formalised Christian doctrine, cementing it as a dominant force in the Roman Empire.

GLOBAL RELIGIONS

Hinduism expanded, developing the Bhagavad Gita, which explored duty and spirituality.

Shintoism in Japan emphasised reverence for kami (spirits) and ancestral worship.

ISLAMIC GOLDEN AGE

Avicenna and Averroes bridged Greek philosophy with Islamic theology, influencing Western thought during the Renaissance.

500 YEARS AGO: THE RENAISSANCE AND REFORMATION

THE REBIRTH OF REASON

The Renaissance (14th–17th centuries) revived Greek and Roman ideas. Thinkers like Leonardo da Vinci explored science and art, challenging medieval dogma.

Copernicus (1543): Proposed heliocentrism, overturning the geocentric worldview.

THE REFORMATION

Martin Luther (1517): Challenged the Catholic Church’s authority, leading to Protestantism.

400 YEARS AGO: SCIENCE EMERGES

SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642): Pioneered empirical observation, confirming heliocentrism and inventing modern telescopic astronomy.

Francis Bacon (1561–1626): Developed the scientific method, emphasising experimentation over speculation.

EARLY MODERN PHILOSOPHY

Descartes: “Cogito, ergo sum” introduced the split between mind and body.

Hobbes Advocated materialism, viewing life as a “nasty, brutish, and short” struggle for survival.

200 YEARS AGO: DARWIN AND THE ENLIGHTENMENT

DARWIN’S CHALLENGE

On the Origin of Species (1859) undermined creationism, showing that life evolved through natural selection.

Darwin’s work sparked debates about humanity’s place in a universe governed by blind processes.

THE ENLIGHTENMENT

Thinkers like Voltaire and Diderot questioned religion’s authority, advocating for reason, liberty, and progress.

150 YEARS AGO: THE RISE OF EXISTENTIALISM

EXISTENTIALISM’S BIG QUESTIONS

Kierkegaard: Explored faith, angst, and the individual’s relationship with God.

Nietzsche Declared, “God is dead,” critiquing organised religion’s moral authority and heralding the rise of individual will.

Dostoevsky: Examined the psychological and moral crises of faith (The Brothers Karamazov).

70-100 YEARS AGO: LOGIC, SCIENCE, AND HUMAN EXISTENCE

FALSIFIABILITY AND PARADIGMS

Karl Popper: Argued science progresses through falsification, not confirmation.

Thomas Kuhn: Highlighted paradigm shifts in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, emphasising science’s non-linear progress.

LOGICAL ANALYSIS

Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein formalised logical analysis, reshaping philosophy.

EXISTENTIALISM’S PEAK

Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus: Explored freedom, absurdity, and the human condition. Sartre’s Being and Nothingness posited that existence precedes essence, while Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus examined life’s meaninglessness.

20 YEARS AGO: THE MODERN DEBATE

THE NEW ATHEISTS

Thinkers like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens criticised religion as outdated and harmful, advocating for science and secular ethics.

SIMULATION THEORY

Philosophers like Nick Bostrom suggested reality might be a simulation, sparking debates about metaphysics and epistemology.

BEYOND SCIENCE: GENDER IDEOLOGY AND MODERN BELIEFS

GENDER IDEOLOGY

Critics argue that modern concepts of gender rely more on metaphysical beliefs than empirical science, blending identity politics with sociocultural constructs.

POST-TRUTH AND CANCEL CULTURE

The digital age has brought misinformation and the rejection of scientific and historical principles, fuelling debates about authority and truth.

REFERENCES

Murdock, G. P. (1932). The science of culture: A study of man and civilization. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Boyer, P. (2001). Religion explained: The evolutionary origins of religious thought. Basic Books.

Guthrie, S. E. (1993). Faces in the clouds: A new theory of religion. Oxford University Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Hawking, S. (1988). A Brief History of Time. Bantam Books.

Dennett, D. C. (2006). Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. Viking.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural Anthropology. Basic Books.

Popper, K. R. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press. ISBN-13: 978-0226578069.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1848). The Communist Manifesto. Verso. ISBN-13: 978-1844670865

Pinker, S. (2002). The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Penguin.

Tylor, E. B. (1871). "Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom". John Murray.

Dawkins, R. (2006). The God Delusion. Bantam Press. ISBN-13: 978-0593058251.

Whitaker, R. (2002). Mad in America: Bad Science, Bad Medicine, and the Enduring Mistreatment of the Mentally Ill. Basic Books.

Joyce, H. (2021). Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality. Oneworld Publications.

Hitchens, C. (2007). God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. Twelve.

ATHEISTS AND AGNOSTICS

The concept of atheism, the lack of belief in gods or the denial of their existence, has a long history. However, pinpointing the "first atheists" is challenging due to the evolution of religious and philosophical thought over millennia. However, some ancient figures and schools of thought are often cited as early examples of atheistic or non-theistic beliefs:

ANCIENT INDIAN PHILOSOPHY: In ancient India, several schools of thought questioned the existence of deities. For instance, the Carvaka or Lokayata school, dating back to around the 6th century BCE, is considered one of the earliest forms of explicit atheism. They rejected the supernatural, advocating for a materialistic view of the world.

CLASSICAL GREEK PHILOSOPHY: Several pre-Socratic Greek philosophers, such as Democritus (c. 460 – c. 370 BCE), who proposed an early form of atomism, are sometimes considered atheistic or agnostic in their views. They did not necessarily deny the existence of gods but often depicted them as unconcerned with human affairs and proposed naturalistic explanations for phenomena traditionally attributed to divine intervention.

EPICUREANISM: Founded by Epicurus in the 3rd century BCE, this school of thought didn't explicitly deny the existence of gods but argued that they were not involved in human affairs. The focus was on seeking happiness by pursuing knowledge and avoiding pain, emphasizing the material world.

DIAGORAS OF MELOS: Often referred to as the "first atheist," Diagoras (c. 5th century BCE) was a Greek poet and sophist. He is known for his scepticism towards religion and the existence of gods, although details about his life and beliefs are sparse and mainly known through later sources.

XENOPHANES OF COLOPHON: A pre-Socratic philosopher (c. 570 – c. 475 BCE), Xenophanes is noted for criticizing anthropomorphic depictions of gods and challenging traditional religious beliefs of his time

These early examples represent a more sceptical or critical approach to traditional theism than atheism in the modern sense. The term "atheist" itself, especially in ancient times, often had negative connotations and was sometimes used to describe people who rejected the traditional gods of their culture rather than denying the existence of any deities whatsoever.

The development of atheistic thought is intertwined with the broader history of religious and philosophical inquiry, and as such, the concept of atheism has evolved significantly over time.

FROM THE 17 CENTURY UNTIL THE PRESENT TIME

BARUCH SPINOZA (1632-1677): A Dutch philosopher of Portuguese Sephardi Jewish origin, Spinoza is often considered an early proponent of atheism or radical pantheism. His philosophical work, particularly "Ethics," challenged traditional religious views, proposing a God synonymous with nature and dismissing divine intervention. His ideas led to his excommunication from the Jewish community.

THOMAS HOBBES (1588-1679): Although not strictly an atheist, Hobbes, a materialist, laid the foundation for modern political philosophy in his work "Leviathan." He promoted a secular and naturalistic view of the world, advocating for a social contract theory based on reason rather than religious authority.

BARON D'HOLBACH (1723-1789): Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach, an 18th-century French philosopher and encyclopaedist, was known for his atheistic and materialistic views. He hosted a renowned salon in Paris for Enlightenment thinkers, becoming a pivotal figure in spreading atheist and freethinker ideologies.

DAVID HUME (1711-1776): Hume, a Scottish philosopher, is recognised for his sceptical approach to religion. His empiricist philosophy and critical analysis of religious claims, especially miracles, have significantly impacted the philosophy of religion and agnostic thought.

JULIEN OFFRAY DE LA METTRIE (1709-1751): A French physician and philosopher, La Mettrie is known for his materialist and atheistic views. His controversial work "Man a Machine" argued for a mechanistic understanding of human nature, challenging the existence of a soul and traditional religious concepts.

THOMAS HUXLEY (1825-1895): Often referred to as "Darwin's Bulldog," Huxley was a prominent agnostic known for his defence of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. He advocated for scientific inquiry over religious belief, coining the term "agnostic" to describe his stance on the unknowability of spiritual matters.

CHARLES DARWIN (1809-1882): Famous for his theory of evolution by natural selection, Darwin's work had profound implications for religious beliefs about creation. While his scientific work challenged traditional religious views, Darwin himself did not explicitly identify as an atheist, preferring to describe himself as an agnostic, especially in his later years.

KARL MARX (1818-1883): Marx, a philosopher, economist, and revolutionary socialist, is known for his atheistic views. He considered religion to be "the opium of the people," a tool of oppression that reflects and perpetuates societal inequalities.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE (1844-1900): Nietzsche's philosophy included a radical critique of religion, particularly Christianity. His famous statement "God is dead" reflects his belief that traditional religious values had become irrelevant in the modern world.

SIGMUND FREUD (1856-1939): The founder of psychoanalysis, Freud viewed religious belief as an illusion, a psychological mechanism to fulfil human emotional desires. He considered religion to be a collective neurosis.

BERTRAND RUSSELL (1872-1970): An influential British philosopher and logician, Russell advocated for atheism and rational inquiry. His essay "Why I Am Not a Christian" outlines his reasons for rejecting Christianity and other religions.

ALBERT EINSTEIN (1879-1955): Einstein's views on religion were complex; he did not believe in a personal God and often expressed agnostic views. He used the term "God" metaphorically, referring to the underlying order of the universe.

VICTOR J. STENGER (1935-2014): An American physicist and philosopher, Stenger was a vocal critic of religion and supernatural claims. His book "God: The Failed Hypothesis" argues that science disproves the existence of God.

CARL SAGAN (1934-1996): An American astronomer and science communicator, Sagan was known for his agnostic views. He promoted scientific scepticism and inquiry, emphasising the vast, unexplained mysteries of the universe.

STEPHEN HAWKING (January 8, 1942 – March 14, 2018): The renowned theoretical physicist, celebrated for his scientific contributions and known for his atheist views.

RICHARD DAWKINS (1941-Present): An evolutionary biologist, Dawkins is a leading figure in the New Atheism movement. His book "The God Delusion" critiques religion and argues against the existence of a deity.

DANIEL DENNETT (Born 1942): A philosopher and cognitive scientist, Dennett is one of the "Four Horsemen" of New Atheism. He views religion as a natural phenomenon that should be studied scientifically.

SAM HARRIS (Born 1967): As a neuroscientist and author, Harris is part of the "Four Horsemen" of New Atheism. He criticises religion and advocates for a secular, rational basis for morality.

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS (1949-2011): A British-American author and journalist, Hitchens was known for his articulate atheism and criticism of religion, notably in his book "God Is Not Great."

MICHAEL SHERMER (Born 1954): Founder of The Skeptics Society, Shermer advocates for scientific scepticism and critiques religious and supernatural claims from a scientific viewpoint.

MICHEL ONFRAY (Born January 1, 1959): A French philosopher, Onfray advocates for atheism and hedonism. He's known for his writings on materialism and atheistic thought.

A.C. GRAYLING (Born 1949): A British philosopher and writer, Grayling is a proponent of humanism and secularism, often engaging in public discourse on religion and ethics.

JERRY COYNE (Born 1949): An American biologist, Coyne is known for his vocal atheism and critiques of creationism and intelligent design, advocating for the acceptance of evolutionary biology.

AYAAN HIRSI ALI (Born 1969): A Somali-born Dutch-American activist and former politician, Hirsi Ali criticises Islam and advocates for atheism and women's rights.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON (Born 1958): An American astrophysicist and science communicator, Tyson describes himself as agnostic, emphasising the importance of scientific literacy and a secular worldview.

LAWRENCE KRAUSS (Born 1954): A theoretical physicist and cosmologist, Krauss advocates for atheism and scientific understanding, often discussing the incompatibility of science and religious dogma.

KATHARINE HAYHOE (Born 1972): A climate scientist, Hayhoe is an agnostic who emphasises the compatibility of science and faith, particularly in environmental stewardship.

STEVEN PINKER (Born 1954): A cognitive psychologist and linguist, Pinker approaches human nature from an agnostic perspective, often discussing the intersection of science, reason, and humanism.

CELEBRITIES THAT DON’T BELIEVE IN GOD

Famous individuals who have identified as atheist or agnostic

CHARLIE CHAPLIN (April 16, 1889 – December 25, 1977): Actor and filmmaker known for his agnostic views.

KATHARINE HEPBURN (May 12, 1907 – June 29, 2003): Legendary actress known for her outspoken atheism.

CARL SAGAN (November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996): Astronomer and cosmologist, identified as agnostic, promoting scientific scepticism and wonder.

BRUCE LEE (November 27, 1940 – July 20, 1973): Martial artist and actor known for his philosophical views, including elements of agnosticism.

JOHN LENNON (October 9, 1940 – December 8, 1980): Musician and member of The Beatles, expressed atheistic views, especially in "Imagine."

KURT VONNEGUT (November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007): American author known for his humanist and atheist beliefs.

WARREN BUFFETT (Born August 30, 1930): Investor, described himself as agnostic.

IAN MCKELLEN (Born May 25, 1939): Renowned British actor, identified as an atheist.

LAWRENCE KRAUSS (Born May 27, 1954): Theoretical physicist and cosmologist, advocate for atheism and scientific understanding.

JAMES CAMERON (Born August 16, 1954): Film director known for his agnostic views.

NEIL PEART (September 12, 1952 – January 7, 2020): Drummer for Rush expressed agnostic and atheist views.

BILLY JOEL (Born May 9, 1949): American singer-songwriter, identified as an atheist.

BILL GATES (Born October 28, 1955): Co-founder of Microsoft, Gates has described himself as agnostic when it comes to discussing religious beliefs

PENN JILLETTE (Born 1955): An American magician and author, Jillette is a vocal atheist, often discussing his views on religion and scepticism.

BILL MAHER (Born 1956): An American comedian and political commentator, Maher is known for his satirical critique of religion and identifies as agnostic.

STEPHEN FRY (Born 1957): An English actor and writer, Fry advocates for humanism and atheism, often addressing religious themes in his work.

JULIA SWEENEY (Born October 10, 1959): Comedian and actress known for her one-woman show "Letting Go of God."

HUGH LAURIE (Born June 11, 1959): British actor known for his atheist views.

SETH MACFARLANE (Born October 26, 1973): Creator of "Family Guy," spoken about his atheism.

KATHY GRIFFIN (Born November 4, 1960): Comedian and actress, self-proclaimed atheist.

GEORGE CLOONEY (Born May 6, 1961): Actor and director, expressed agnostic leanings.

RICKY GERVAIS (Born June 25, 1961): Comedian and actor recognised for his outspoken atheism.

JODIE FOSTER (Born November 19, 1962): Actress and director, expressed agnostic beliefs.

BRAD PITT (Born December 18, 1963): Actor oscillating between atheism and agnosticism.

ANGELINA JOLIE (Born June 4, 1975): Actress and filmmaker, described herself as agnostic.

UMA THURMAN (Born April 29, 1970): Actress known for her agnostic beliefs.

JULIAN ASSANGE (Born July 3, 1971): WikiLeaks founder described himself as an atheist.

LANCE ARMSTRONG (Born September 18, 1971): Former professional cyclist, identified as an atheist.

JOAQUIN PHOENIX (Born October 28, 1974): Actor described his religious views as agnostic.

BJÖRK (Born November 21, 1965): Icelandic singer-songwriter known for her atheist views.

NATALIE PORTMAN (Born June 9, 1981): Academy Award-winning actress, expressed agnostic views.

MARK ZUCKERBERG (Born May 14, 1984): Facebook founder, raised Jewish, described himself as an atheist but recently reconsidering.

ZAC EFRON (Born October 18, 1987): American actor, described himself as agnostic.

KEIRA KNIGHTLEY (Born March 26, 1985): Actress who spoke openly about her atheism.

DANIEL RADCLIFFE (Born July 23, 1989): Actor, identified as an atheist