THE PSYCHODYNAMIC APPROACH

SPECIFICATION: THE PSYCHODYNAMIC APPROACH

The role of the unconscious

The structure of personality, that is Id, Ego and Superego

Defence mechanisms including repression, denial and displacement, Psychosexual stages

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

PSYCHOANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE: This perspective is rooted in the original works of Sigmund Freud and encompasses theories and therapeutic methods that delve into the unconscious mind to understand and address psychological issues.

PSYCHODYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE: In contrast to the emphasis on sexuality in psychoanalysis, the psychodynamic perspective places greater importance on the role of the social environment in shaping one's personality and behaviour.

PSYCHOANALYSIS: This term refers to the therapeutic techniques and methods used within the psychoanalytic perspective. It involves exploring the unconscious mind to gain insights into a person's thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

TRANSFERENCE: Transference occurs when individuals project emotions or feelings for one person onto someone else. In therapy, it can be a valuable tool for therapists to gain a deeper understanding of a patient's experiences and emotions.

CATHARSIS (FREUD)

The emotional release of repressed aggressive or sexual energy, often achieved through expression or symbolic acts, provides psychological relief.

EGO DEFENCE MECHANISM

The ego uses Unconscious strategies to manage conflict between the id and superego, helping reduce anxiety and tension. Examples include repression, displacement, and sublimation.

PSYCHOANALYSIS

In Freud’s psychoanalysis, therapy involves uncovering unconscious conflicts and repressed emotions through techniques like free association and dream analysis, aiming to resolve internal tensions and improve psychological well-being

COUNTER-TRANSFERENCE: Counter-transference refers to the therapist's emotional reactions and attitudes toward the patient. It includes the therapist's responses to the patient's transference, personal experiences that may impact their understanding of the patient and emotional reactions towards the patient.

PARAPRAXIS (FREUDIAN SLIP): Also known as a Freudian slip, a parapraxis is a mistake or error, such as a slip of the tongue or forgetting someone's name, that reveals an unconscious desire, thought, or conflict.

FANTASY: A fantasy is an imagined scenario that expresses an individual's desires or aspirations. It can be conscious, such as daydreaming, or unconscious, referred to as "phantasy."

RESISTANCE: Resistance in psychoanalysis refers to a patient's unconscious opposition to the exploration and revelation of painful memories during therapy. It can manifest through various mental processes, fantasies, memories, character defences, and behaviours. Importantly, it may persist even after the patient becomes consciously aware of it.

CONFRONTATION: Confrontation in therapy involves encouraging patients to face and address experiences or emotions they have been avoiding. It is a therapeutic technique aimed at facilitating personal growth and self-awareness.

GRATIFICATION: Gratification denotes the experience of pleasure or satisfaction, whether it pertains to sexual pleasure, the satisfaction of basic needs like food and warmth, or other sources of contentment.

INSTANT GRATIFICATION: This term describes the inclination to choose immediate pleasure or rewards over waiting for a potentially more substantial but delayed benefit. It often involves the pursuit of immediate pleasure without considering long-term consequences.

OVER-GRATIFICATION: Over-gratification refers to not receiving sufficient pleasure or fulfilment at a particular stage of personality development, potentially leading to psychological issues later in life.

UNDER-GRATIFICATION: Conversely, under-gratification refers to receiving excessive pleasure or satisfaction at a specific stage of personality development, which can also affect psychological development.

PLEASURE PRINCIPLE: The pleasure principle, associated with the id in Freud's model of the mind, represents the innate drive to seek immediate gratification of one's needs to experience pleasure and avoid pain. When basic needs are not met, it can lead to feelings of anxiety.

REALITY PRINCIPLE: In Freudian psychology, the reality principle contrasts with the pleasure principle. It refers to the mind's ability to assess external reality and adapt behaviour accordingly, considering immediate pleasure and the consequences of actions.

EGO IDEAL: Part of the superego, the ego ideal comprises standards, values, and moral ideals that an individual internalizes. Failure to meet these standards can result in guilt, while success can enhance self-esteem.

EROGENOUS ZONES: Erogenous zones are areas of the body that are particularly sensitive to stimulation and can elicit pleasurable sensations. Freud associated specific erogenous zones with different stages of psychosexual development.

FIXATION: Fixation occurs when an individual becomes overly attached or invested in a particular developmental stage due to unresolved conflicts during that stage. This fixation can influence later behaviour and personality traits.

LIBIDO: The term libido encompasses one's sexual desires and, more broadly, the mental energy responsible for one's sex drive. According to Freud, this concept suggests that sexual interest persists throughout life and plays a role in various activities involving sexual desire or affection.

THANATOS: In Freudian theory, Thanatos represents the death drive, highlighting the inherent tendency toward entropy and the dissolution of life forces. It counterbalances the life drive, known as Eros, which strives to sustain life.

EROS: Eros, the life force, represents the drive to sustain and propagate life. It encompasses the desires and attractions that promote life and connection.

THE OEDIPUS COMPLEX: Freud used the Oedipus complex to describe a developmental stage in childhood, typically occurring between ages three and six. It involves a child's desire to have a parent of the opposite sex exclusively, excluding the other parent. This concept is drawn from the Greek myth of Oedipus.

THE ELEKTRA COMPLEX: Coined by Jung as the female counterpart to the Oedipus complex, the Elektra complex describes a young girl's desire to have her father to herself while excluding her mother. Freud continued to use the term Oedipus complex for both genders but acknowledged the existence of a similar phenomenon in girls.

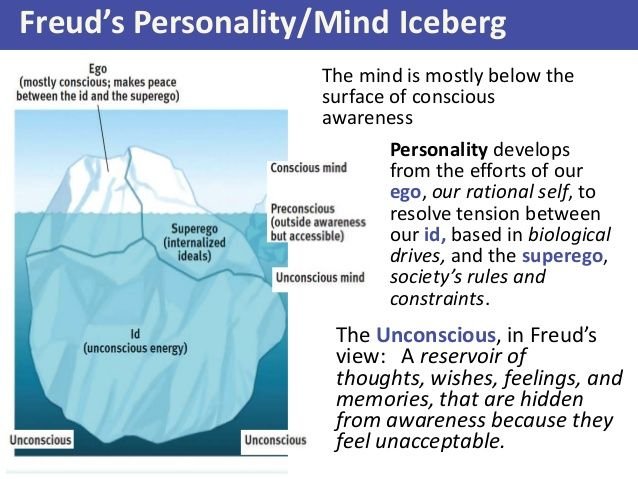

THE ICEBERG ANALOGY OF THE PSYCHE

FREUD’S CONCEPT OF THE PSYCHE

Freud introduced the term psyche to describe the entirety of the human mind, encompassing thoughts, feelings, and unconscious processes. He viewed the psyche as dynamic, constantly shaped by internal conflicts between instinctual desires, morality, and reality.

Freud proposed that the psyche operates on three levels of awareness:

Conscious – The part of the psyche that contains thoughts and feelings we are actively aware of.

Preconscious – The "bridge" between the conscious and unconscious, containing memories and information that can be accessed with effort.

Unconscious – The largest, most hidden part of the psyche, housing repressed memories, desires, and instincts that influence behaviour without our awareness.

To explain this, Freud compared the psyche to an iceberg. Only a small portion—about one-tenth—is visible above the surface, representing the conscious mind. The vast majority of the iceberg, hidden beneath the water, represents the preconscious and unconscious, where powerful and unseen mental processes reside.

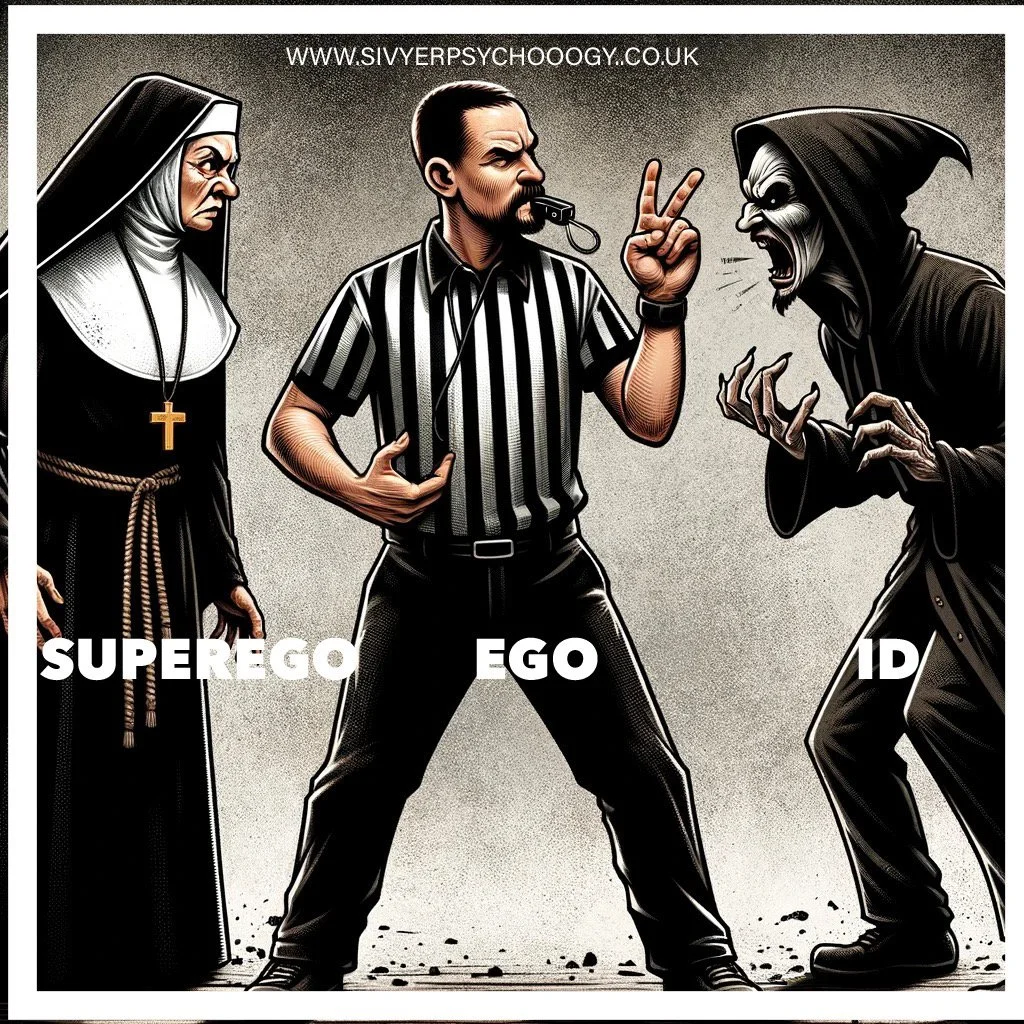

THE TRIPARTITE STRUCTURE OF THE PSYCHE

Freud further divided the psyche into three interacting components, which he referred to as the tripartite personality:

Id:

The most primitive part of the psyche, present from birth.

Operates on the pleasure principle, seeking immediate gratification of basic drives such as hunger, libido, and aggression.

Entirely unconscious, the id is the source of instinctual energy.

Ego:

The rational, decision-making component that operates on the reality principle.

Mediates between the demands of the id, the moral constraints of the superego, and the reality of the external world.

Spans the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious realms.

Superego:

The moral conscience, formed during early childhood through internalisation of societal and parental values.

Operates on the morality principle, creating feelings of guilt when behaviour conflicts with internalised standards.

Exerts influence across the preconscious and unconscious.

INTERACTION OF THE PSYCHE’S LEVELS AND STRUCTURE

The three levels of awareness and the tripartite structure of the psyche work together dynamically:

The conscious mind primarily involves the ego, which manages real-time decisions.

The preconscious mind is accessed by both the ego and superego for memories, strategies, and moral reasoning.

The unconscious mind is dominated by the id, with repressed material kept hidden by the superego.

Conflicts between these components—such as the id’s desires clashing with the superego’s moral standards—are managed by the ego through defence mechanisms like repression, displacement, and sublimation.

A NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY

Freud deliberately used the term "unconscious" instead of "subconscious" to emphasise its active and dynamic nature. The unconscious is not simply below awareness but repressed and inaccessible, influencing behaviour in profound, unseen ways.

SUMMARY

Freud’s concept of the psyche integrates the three levels of awareness and the tripartite personality, offering a framework to understand how internal conflicts and hidden processes shape human behaviour. His iceberg analogy vividly illustrates how much of the mind operates beneath the surface, beyond our conscious awareness, and highlights the complex interplay between instinct, morality, and reality.

THREE PARTS OF THE PSYCHE: THE TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY

According to Freud, the three parts develop over the first five years of early life. Thus, for Freud, early childhood is the most critical stage in human life as it is when the psyche forms and shapes behaviour for the entire life span.

THE ID = THE DEVIL

THE iD IS PRESENT FROM BIRTH

THE iD = THE DEVIL

The id is present from birth. It is the most fundamental aspect of the psyche, first developing in babies. The id is comprised of urges and desires. It lacks rationality and reflection, consisting entirely of feelings. It resides wholly in the unconscious mind. Many of us share similar id-driven desires: food, drink, sex, sleep, and fun. The id operates on the "pleasure principle" without comprehending logic, time, or the external world. It demands immediate gratification; it wants what it wants and wants it NOW. Denying the id its pleasure can lead to frustration. The id itself is not evil; most of its desires are essential for our well-being – without eating or sleeping, we would perish, and the continuation of our species relies on sexual reproduction. The challenge lies in the id's inability to impose restraint, delay gratification, or acknowledge others. It lives solely for the moment and is entirely self-centred. However, immediately satisfying these needs isn't always practical or feasible. If the pleasure principle entirely governed us, we might grab desired items from others to fulfil our cravings. Such behaviour would be disruptive and socially unacceptable. According to Freud, the id attempts to resolve the tension arising from the pleasure principle through the primary process involving the creation of a mental image of the desired object to satisfy the need.

It's important to note that the “id” is distinct from "ID" as in an identification card or identity.

IN SHORT

The ID = The Devil: This analogy suggests that the id can be viewed metaphorically as the "devil" within us, representing our most basic, impulsive, and often selfish desires.

Present from Birth: According to Freud, the id is present from birth and represents the most primitive part of the psyche.

Urges and Desires: The id is primarily driven by urges and desires, operating to fulfil immediate needs.

Unconscious: The id operates entirely within the unconscious mind, meaning its processes and desires are not readily accessible to conscious awareness.

Feelings over Logic: Unlike the ego and superego, the id is not rational or reflective. It is primarily composed of raw emotions and desires.

Pleasure Principle: The id operates based on the pleasure principle, seeking immediate gratification of its desires without considering logic, time, or external constraints.

Immediate Gratification: The id seeks what it wants immediately and lacks patience for delay or postponement. It operates on a "want it now" basis.

THE EGO =THE REFEREE

THE EGO DEVELOPS IN THE FIRST THREE YEARS OF LIFE

The ego is the second part of the psyche, typically developing in toddlers. It serves as the thinking and decision-making component of the mind. Unlike the id, the ego operates within the conscious mind and adheres to the "reality principle." This means it comprehends the outside world, the consequences of actions, and the passage of time. Notably, the ego does not possess its desires; instead, it is to find ways to fulfil the desires emanating from the id. This is possible because the ego understands the real world and can formulate plans and strategies.

The ego plays a crucial role in managing the id's impulses in a socially acceptable manner, ensuring that desires can be expressed in ways suitable for the real world. It functions in the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious mind. Based on the reality principle, the ego seeks to satisfy the id's desires realistically and socially appropriately. It carefully assesses the costs and benefits of actions before deciding to act upon or suppress impulses. In many instances, the ego allows the satisfaction of id impulses through delayed gratification, permitting the behaviour at the appropriate time and place. The ego also relieves tension from unmet impulses through the secondary process, which involves searching for real-world objects that match the mental images created by the id's primary process.

TWO PRINCIPLES TO CONSIDER

Freud contrasted the pleasure principle with its counterpart, the reality principle. The pleasure principle drives the need for immediate gratification, while the reality principle reflects the ability to defer gratification when external circumstances prevent immediate satisfaction.

In infancy and early childhood, behaviour is governed by the id, which operates entirely under the pleasure principle. At this stage, individuals seek instant gratification to satisfy basic cravings like hunger and thirst. As development progresses, the id also begins to pursue desires linked to sex and aggression.

Maturity involves learning to endure the discomfort of deferred gratification. This is one of the ego's most powerful tools for managing the id. Deferred gratification means postponing immediate pleasure or opting for a more minor, less satisfying pleasure now in exchange for a greater reward later. The ego achieves this by "persuading" the id. For example, the ego might convince the id to complete an unpleasant task, like household chores, by promising a more enjoyable reward later, such as eating pizza.

It's worth noting that while the ego understands punishment and tries to avoid it, it does not experience guilt—that is the domain of the superego.

Freud argued:

"An ego thus educated has become 'reasonable'; it no longer lets itself be governed by the pleasure principle but obeys the reality principle, which also, at the bottom, seeks to obtain pleasure, but pleasure which is assured through taking account of reality, even though it is pleasure postponed and diminished.”

Freud’s statement can be summarised as:

"A well-developed ego becomes rational and mature. It no longer blindly follows the immediate demands of the pleasure principle but adapts to the reality principle. While it still seeks pleasure, it does so in a way that takes real-world constraints into account. The pleasure may be delayed or less intense, but it is more sustainable and realistic."

THE SUPER-EGO = THE ANGEL

THE SUPEREGO DEVELOPS ABOUT THE AGE OF FIVE.

THE SUPER-EGO: MORALITY AND CONSCIENCE

Development and Role: The final component of the psyche to develop is the super-ego, which typically forms between the ages of 4 and 6. This aspect of personality holds our internalised moral standards and ideals acquired from parents and society, shaping our sense of right and wrong. The super-ego operates at the intersection of the conscious and unconscious mind, with partial awareness. It operates based on the "morality principle" and serves as the "voice of conscience," evaluating the moral acceptability of the ego's thoughts and actions.

Guilt and Shame: When the super-ego objects to the ego's thoughts or actions, it triggers feelings of guilt and shame. These emotions can be challenging for the ego to endure, leading it to generate thoughts and plans that align with the super-ego's moral standards. This can be a complex process, as the id continues to generate needs and desires that may conflict with the super-ego's moral restrictions.

Understanding the Super-Ego: It's important to clarify that the super-ego isn't inherently "good," nor is the id "evil." The super-ego represents the desire for self-punishment, feelings of unworthiness, and a sense of failure. A powerful super-ego doesn't necessarily make an individual a morally upright person. In fact, Freud suggests that individuals with powerful super-egos may commit crimes due to an unconscious desire for punishment.

TWO COMPONENTS OF THE SUPER-EGO

Ego Ideal: This aspect includes rules and standards for good behaviour, reflecting the behaviours approved of by parental and authority figures. Adhering to these rules generates feelings of pride, value, and accomplishment.

Conscience: The conscience contains information about behaviours viewed as bad by parents and society. These behaviours are often forbidden and lead to negative consequences, punishments, or feelings of guilt and remorse.

Role Across Consciousness Levels: The super-ego operates in the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious mind, striving to refine and civilize human behaviour. It aims to suppress unacceptable id impulses and guide the ego toward idealistic standards rather than purely realistic principles.

THE EGO'S DEFENCE MECHANISMS AND THE UNCONSCIOUS

CONFLICT RESOLUTION

VARIATIONS IN THE TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY

Freud’s theory of the TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY highlights the dynamic interplay and potential conflict between the id, ego, and superego. These three components represent competing forces within the psyche: the id demands immediate gratification, the superego enforces moral standards, and the ego mediates between them while considering reality.

Freud introduced the concept of EGO STRENGTH to describe the ego’s ability to manage these duelling forces. A person with strong ego strength can effectively balance the demands of the id, superego, and reality, resulting in adaptive behaviour. However, individuals with too much or too little ego strength may become overly rigid or impulsive, leading to maladaptive behaviours.

Freud compared the id and superego to a horse and the ego to the horse’s rider. The HORSE (the id) provides power and motion, driven by instinctual desires, while the RIDER (the ego) offers direction and guidance. Without the rider’s control, the horse would wander aimlessly, acting solely on impulse. The rider, however, guides the horse towards a purposeful path. According to Freud, a healthy personality requires the rider to maintain balance and control over the horse, reflecting harmony between the id, ego, and superego.

The ego is tasked with mediating the id's demands, the constraints of reality, and the moral expectations of the superego. To navigate these conflicts, the ego employs defence mechanisms. These unconscious strategies help protect the psyche by:

Restricting or modifying the id’s impulses into acceptable forms.

Mitigating guilt or anxiety imposed by the superego.

Blocking aspects of reality that overwhelm the ego, frighten the id, or conflict with the superego’s moral standards.

PROTECTING THE PSYCHE

Defence mechanisms act as safeguards against unpleasant or threatening thoughts and emotions, such as those involving sex, aggression, or hate. They also help mitigate maladaptive behaviours like addiction, overeating, revenge, or anxiety. Defence mechanisms transform unconscious desires into disguised forms, allowing the ego to maintain psychological balance without confronting these impulses' raw and often uncomfortable nature.

FREUD’S VIEW ON DEFENCE MECHANISMS

Freud believed that defence mechanisms are universal; everyone uses them to preserve emotional and psychological well-being. However, when defence mechanisms dominate as the primary way of coping with stress, they can become maladaptive. While they serve to protect the mind, they often involve self-deception or distortions of reality, which can prevent individuals from addressing the root causes of their distress.

Freud also noted that these mechanisms are typically learned during early childhood and develop in response to feelings of hurt, pain, anger, anxiety, sadness, or low self-worth. Over time, they become automatic and habitual, operating unconsciously in daily life.

IMPLICATIONS OF DEFENCE MECHANISMS

Understanding defence mechanisms provides insight into how the psyche maintains balance in internal and external challenges. While they are necessary for coping, excessive reliance on them can hinder emotional growth and problem-solving, leading to unresolved psychological issues.

EGO DEFENCE MECHANISMS.

ACCUSING: Blaming someone or something else for one's behaviour, such as accusing others of causing one's drinking or drug use.

ANALYSING: Engaging in rationalisation by justifying increased substance use due to a specific reason, often with the belief that it will decrease over time.

ARGUING: Denying an addiction problem by pointing out that no severe consequences, such as fines or legal issues, have occurred.

ATTENTION-GETTING: Creating situations that make oneself appear necessary or the victim to divert attention from underlying feelings of failure and insecurity.

BLAMING: Holding others responsible for one's substance abuse, like attributing it to job stress or external factors.

COCKINESS: Overcompensating for insecurities by adopting an arrogant or overly confident attitude, viewing oneself as superior to others.

COMPENSATION: Masking personal weaknesses by highlighting desirable qualities or attempting to compensate for frustrations in one area of life with excessive gratification in another.

COMPLIANCE: Conforming to others' expectations and demands to avoid facing personal issues or conflicts.

CONVERSION: Transforming emotional struggles into physical symptoms or ailments, effectively transferring psychological distress into bodily complaints.

DEFIANCE: Challenging others to prove one's addiction is often used as a defence mechanism to deny the problem.

DENIAL OF REALITY: Refusing to acknowledge or face an unpleasant reality or situation to protect oneself from its emotional impact.

DISPLACEMENT: Redirecting intense emotions, typically hostility, from their initial source to less threatening objects or individuals.

EMOTIONAL INSULATION: Reducing emotional engagement and adopting a passive demeanour to shield oneself from emotional hurt.

EXPLAINING: Offering justifications or explanations for one's substance abuse, attempting to rationalise or excuse the behaviour.

FANTASY: Escaping into imaginary achievements or idealised scenarios to fulfil unmet desires or cope with reality, often used as an excuse by individuals struggling with addiction.

HUMOUR: Using humour to downplay the seriousness of an issue, including addiction, as a way to avoid confronting it.

IDEALISATION: Extensively admiring oneself or others, often to an unrealistic and exaggerated degree.

IDENTIFICATION: Aligning oneself with another person, group, or profession to overcome feelings of inferiority or insecurity.

INTELLECTUALISING: Attempting to analyse and intellectualise the problem by citing research or data that suggests the absence of an addiction issue.

JUDGING: Blaming others for their problems or challenges, suggesting that things would improve if they behaved differently.

JUSTIFYING: Providing reasons or excuses to rationalise substance abuse, often by shifting blame to external factors or circumstances.

LYING: Misrepresenting the extent of substance use, minimising it to appear less problematic.

MANIPULATION: Using manipulative tactics, such as making deals or promises, to divert attention from one's addiction or to avoid confrontation.

MINIMISING: Downplaying one's substance use by comparing it to others, making it seem less severe than it is.

PROJECTING: Attributing one's manipulative behaviours or desires to others, deflecting attention from one's actions.

PROJECTION: Placing blame on others for difficulties or projecting one's unethical desires onto them.

RATIONALISING: Justifying one's actions to ease guilt or discomfort, often by emphasising the absence of a daily or constant problem.

REACTION FORMATION: Preventing the expression of undesirable desires by adopting exaggerated opposing attitudes or behaviours as a defence mechanism, for example, being homophobic while secretly harbouring same-sex attractions.

REGRESSION: Seeking to return to a state of childhood and escape adult responsibilities or stressors.

REPRESSION: Keeping distressing or dangerous thoughts and memories out of conscious awareness to avoid confronting them.

SELF-PITY: Attributing personal failures or difficulties to fate or bad luck, adopting a defeatist attitude.

SUBLIMATION: Redirecting one's drives or impulses toward a socially acceptable and productive goal when the original goal becomes unattainable.

THREATENING: Using threats to intimidate or discourage others from confronting or intervening in one's addiction.

WITHDRAWING: Responding to stressors or confrontations by withdrawing from social interactions or emotional engagement. This can manifest as shouting, silence, nervousness, or physical withdrawal.

FREUD’S MODEL OF PSYCHO-SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT

But how does the Tripartite personality develop? In other words, how does somebody become iDd dominant or superego dominant, and if they are lucky, are they balanced? According to Freud, these variations are due to the experiences a person has during their psychosexual development, which takes place during childhood.

Freud observed that children's behaviour often orients around certain body parts like the mouth during breastfeeding, the anus during toilet training, and later the genitals at around the age of four. Because of his work previous work with hysterical patients, Freud also believed that adult neurosis often has roots in childhood sexuality,

Freud proposed that these abnormal behaviours were childhood expressions of sexual fantasy and desire. He suggested that humans are born "polymorphously perverse", meaning that infants can derive sexual pleasure from any part of the body. And that it is only through socialisation that sexual drives are focused on adult heterosexuality.

Freud developed a model for what he considered to be the "normal" sexual development of the child, which he called "libido development". According to this theory, each child passes through five psychosexual stages. During each stage, the libido has a different erogenous zone as the source of its drives. The libido refers to various kinds of sensual pleasures and gratifications.

However, in the pursuit of satisfying these sexual urges, the child may experience failure or reprimands from his parents or society and may thus come to associate anxiety with this erogenous zone. To avoid this anxiety, the child becomes preoccupied with themes related to this zone, a phenomenon Freud termed fixation. Freud believed the fixation persists into adulthood and underlies the personality structure and psychopathology, including neurosis, hysteria and personality disorders. Freud called this psychosexual infantilism.

The psychosexual stages are as follows:

ORAL STAGE

AGE RANGE: 0 - 1/2 years

EROGENOUS ZONE(S): Mouth

PART OF TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT: Ego development. Problems at the oral stage can result in a weak Ego or disintegrated Ego.

The oral stage encompasses the initial phase of a child's psychosexual development, extending from birth to roughly 21 months of age. During this period, the infant's primary source of pleasure and exploration is centred on their mouth and lips. These oral activities mainly revolve around sucking and feeding, which are essential for their survival and nourishment.

Infants in the oral stage display a characteristic behaviour of putting various objects into their mouths, including hands, fingers, toys, pacifiers, and even items of clothing, to explore and understand the world around them. This oral exploration is a fundamental way for infants to interact with and learn about their environment.

One of the central elements of the oral stage is breastfeeding, particularly from the mother's breast. This act of nursing fulfils the infant's critical need for sustenance and nourishment. It is a dependent act, crucial for the infant's survival, and it plays a defining role during this stage.

In terms of psychological development, the oral stage is characterized by the dominance of the Id, the most primitive aspect of the psyche. Neither the Ego nor the Superego is fully formed at this early stage of life. Consequently, the infant lacks a well-defined sense of self, and the pleasure principle primarily drives their actions. In simple terms, the infant seeks immediate gratification of their desires and needs, guided solely by instinctual impulses.

While the Id holds sway during the oral stage, the formation of the Ego begins to take shape. Two critical factors influence the development of the Ego:

Body Image: Infants begin to differentiate their bodily boundaries from the external world. They gradually learn that sensations such as pain occur when external force is applied to their body. This process contributes to the emerging sense of self or ego.

Delayed Gratification: Experiences involving delayed gratification become significant during this stage. The infant gradually realizes that immediate gratification is not always possible and that specific behaviours can lead to satisfying their needs. For instance, crying, which initially appears purposeless, becomes a productive way to communicate needs.

A significant event in the oral stage is weaning, which involves the gradual withdrawal of the infant from their primary source of nourishment, whether it be the mother's milk, a bottle, or a pacifier. This experience introduces the infant to the first sense of loss and limitation they have ever encountered. It is crucial in developing self-awareness, independence, and trust.

According to Freud, how an individual experiences weaning during this stage can have lasting effects on their adult personality. Fixation during the oral stage can manifest in two primary ways:

Orally Passive Fixation occurs when an infant is overindulged during nursing or weaning. Constantly having their feeding needs met can lead to the development of a dependent, helpless, and entitled adult. Signs of an orally passive fixation may include behaviours such as smoking, drug use, overeating, and obsessions with activities involving the mouth.

Orally Aggressive Fixation: Conversely, when infants face neglect during this stage, experiencing premature termination of nursing or insufficient attention to their needs, they can develop an orally aggressive fixation. This can result in the development of an envious, suspicious, and pessimistic adult personality. Signs may include behaviours like excessive gum-chewing or pen-chewing.

In summary, the oral stage represents a crucial phase in psychosexual development where the infant's interactions with feeding, weaning, and oral exploration significantly shape their early experiences and have lasting implications for their adult personality and behaviours. The stage represents the dominance of the Id and the beginning of Ego formation, along with crucial lessons about delayed gratification and self-awareness. The consequences of fixation during this stage can lead to either passive or aggressive behaviours in adulthood. Cultural variations may influence the duration of breastfeeding during this stage, but the act of sucking and eating remains universal early memory for infants across societies.

ANAL STAGE

AGE RANGE: 2-3 years

EROGENOUS ZONE(S): Bowel and bladder elimination

PART OF TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT: EGO Obsession with organisation or excessive neatness

When parents adopt an authoritarian approach to a child's toilet training, involving scolding, punishments, or disappointment, it can have a profound impact on the child's emerging sense of self-expression. In such situations, emotional suppression, fear, and embarrassment related to emotions may ensue. These emotional consequences can manifest in various ways, ranging from an obsession with maintaining an excessively orderly environment to sexual repression, anxiety, or social phobia.

In cases where parents react strongly to the child's behaviour, compliance might indeed occur, but this often comes at the cost of a weakened sense of self. In such instances, parents assume control of the situation, overshadowing the development of the child's ego. On the contrary, when a child prioritises id-driven desires and parents acquiesce to these demands, it can develop a messy and self-indulgent personality.

The resolution of this conflict can be gradual and non-traumatic or intense and stormy, depending on the methods the parents will use to handle the situation.

PHALLIC STAGE

AGE RANGE: 4-6 years

EROGENOUS ZONE(S): Genitals

PART OF TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT: SUPEREGO

During the phallic stage of psychosexual development, which typically spans from three to five years of age, the primary erogenous zone is the genital area. It's important to note that gratification in this stage does not resemble adult sexuality due to the physical immaturity of children. Nevertheless, genital stimulation is considered pleasurable during this period. Children, particularly boys, may experience erections during sleep, akin to adult males.

Children in this stage become increasingly aware of their bodies and begin to exhibit curiosity about the bodies of their peers and parents. Freud observed common behaviours during this stage, such as children undressing and engaging in "doctor" play or asking their mothers about genital differences. These observations led Freud to conclude that gratification is predominantly focused on and around the genital region during the phallic stage.

The central conflict in this stage is the Oedipal conflict, named after the mythological figure Oedipus, who unintentionally killed his father and entered into a relationship with his mother. Freud applied the term "Oedipal" to both boys and girls, although later analysts introduced the "Electra complex" as a counterpart for females. Initially, the primary caregiver and source of gratification for children of both sexes is typically the mother. However, as children develop, their sexual identity formation leads to shifts in dynamics.

MALES

For boys, the mother becomes an object of desire, while the father becomes a source of jealousy and rivalry. The id seeks to unite with the mother and eliminate the father, but the ego, guided by the reality principle, recognises the father's physical strength. The child also harbours affectionate feelings for the father, one of the primary caregivers. The id's fear that the father will disapprove of these emotions is expressed as castration anxiety, which is irrational and unconscious.

FEMALES

Freud argued that girls undergo a similar psychosexual development as boys. While boys develop castration anxiety, girls experience penis envy—a feeling of envy toward males due to their possession of a penis. This envy arises from the belief that without a penis, females cannot sexually possess the mother as the id desires. Consequently, girls are driven to seek sexual union with their fathers. Girls go through an additional stage where they must relinquish the clitoris's sensitivity and importance to the vagina. This transition marks the girl's movement toward heterosexual femininity and the eventual capacity to give birth, with her child symbolically taking the place of the penis.

In general, Freud believed that the Oedipal conflict experienced by girls was more intense than that experienced by boys, potentially resulting in a more submissive and less confident personality.

RESOLUTION

In both cases, the conflict between id drives and ego is resolved through two primary ego defence mechanisms. One is repression, which blocks memories, impulses, and ideas from conscious awareness but does not resolve the conflict. The second mechanism is identification, where the child incorporates characteristics of the same-sex parent into their ego. In the case of boys, this mechanism is employed to reduce castration fears by making them more similar to their fathers. Girls tend to find identification with their mothers easier, as neither they nor their mothers possess a penis.

Freud's theories regarding feminine sexuality, including penis envy, have faced criticism from gender theory and feminist theory.

FIXATIONS

Failure to resolve the Oedipal conflict can lead to fixation in this stage, resulting in various adult behaviours. Women may strive for superiority over men, exhibit seductive or flirtatious behaviour, or demonstrate excessive submissiveness and low self-esteem. In contrast, men may display excessive ambition and vanity. Overall, the Oedipal conflict plays a crucial role in super-ego development, as it involves internalizing morality through identification with one of the parents. A weak identification with the opposite-sex parent may lead to recklessness or immorality.

HOMOSEXUALITY AND UNRESOLVED CONFLICTS

Sigmund Freud's interpretation of homosexuality, as outlined in his early psychoanalytic theories, posited that homosexuality resulted from unresolved conflicts in psychosexual development. Specifically, Freud suggested that homosexuality could be linked to disturbances during the Oedipal complex or Electra complex stages, depending on an individual's gender.

For male homosexuality, Freud proposed that a boy's unresolved Oedipal complex, where he develops strong feelings of love and attachment to his mother and rivalry with his father, could contribute to homosexual tendencies. According to Freud, if a boy did not successfully resolve this complex by identifying with his father and internalizing societal norms, he might retain his attachment to his mother and develop homosexual inclinations.

THE ELECTRA COMPLEX

For female homosexuality, Freud's theory involved the Electra complex. Freud suggested that a girl's development of penis envy (the envy of the male's perceived anatomical advantage) could lead to unresolved conflicts. If these conflicts persisted, they might contribute to homosexual tendencies in women, as they could seek to compensate for the perceived lack of a penis through relationships with other women.

In later revisions of Freud's theories, particularly by other psychoanalysts, the concept of the Electra complex underwent refinements and extensions. One notable revision was introduced by Carl Jung, who emphasized the importance of the Electra complex in the development of female sexuality. Jung expanded upon Freud's ideas and explored the concept of the "Electra archetype," which encompassed a broader range of experiences and symbols related to female development and individuation.

LATENCY STAGE

AGE RANGE: 7-10 years (until puberty)

EROGENOUS ZONE(S): Dormant sexual feelings

PART OF TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT: None, as all the parts of the tripartite personality are formed in the first five years of life.

The latency stage in psychosexual development represents a period characterized by the consolidation of the habits and behaviours that the child developed in earlier stages. Regardless of whether the Oedipal conflict was successfully resolved during the previous stage, the id's drives do not influence the ego during this latency stage. These drives are considered dormant and concealed (latent), and the gratification experienced by the child is not as immediate as it was in the earlier stages. Instead, pleasure is primarily related to secondary process thinking.

During this stage, the energy previously focused on psychosexual drives is redirected towards new activities, primarily related to education, hobbies, and forming friendships. However, challenges may arise during this stage. Inadequate repression of the Oedipal conflict or the ego's inability to redirect drive energy toward socially acceptable activities can lead to problems in this latency stage of development. These issues may manifest as behavioural or emotional difficulties, potentially impacting the child's overall development.

GENITAL STAGE

AGE RANGE: 11+ years(Puberty and beyond)

EROGENOUS ZONE(S): Sexual interests mature

PART OF TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT: None as all the parts of the tripartite personality are formed in the first five years of life.

The final stage of psychosexual development, known as the genital stage, begins during puberty, typically around the age of twelve, and continues into adulthood, ideally concluding around the age of eighteen when adulthood officially commences. This stage encompasses a significant portion of an individual's life and involves several key developmental tasks.

One primary task during the genital stage is achieving detachment from one's parents. It marks a period where individuals strive to reconcile and come to terms with any unresolved issues or conflicts from their early childhood experiences. Unlike previous stages, the genital stage renews the focus on the genitals, similar to the phallic stage. However, there are crucial differences.

In the genital stage, sexual energy is expressed in the context of adult sexuality. Unlike the phallic stage, where gratification is primarily linked to the satisfaction of primary drives, the ego in the genital stage has matured and employs secondary process thinking. This allows for symbolic gratification, which may involve forming love relationships, starting families, or embracing the responsibilities associated with adulthood. It represents a period of psychological maturation and the development of more complex, adult-oriented relationships and behaviours.

POST-NATAL DEVELOPMENT

Freud emphasised that early childhood is a crucial period for development, as four of the five psychosexual stages occur during this time. He viewed this phase as critical for shaping the psyche and influencing behaviour throughout life.

Freud’s idea of the oral stage aligns with observations of newborns, whose needs are basic and instinctual. Only the brain's right hemisphere is fully active at this stage, which corresponds to Freud’s belief that the id dominates infants. While his suggestion that infants derive sexual pleasure from activities like sucking the teat or putting objects in their mouths remains controversial, it reflects his broader theory that early experiences leave lasting psychological imprints.

As children enter the anal stage in their second year, Freud’s theory begins to align with key developmental milestones. During this time, children significantly advance in language, motor skills, and self-control, with the left hemisphere catching up with the right. Freud linked this stage to the emergence of the ego, as children mediate between their instincts and external demands. However, his assertion that the anus serves as a source of sexual pleasure remains unproven and divisive.

Unlike physical development, Freud argued that challenges often mark transitions between psychosexual stages. Children can become fixated at certain stages, carrying unresolved behaviours into later life. Fixation is akin to jelly setting—it becomes permanent and cannot be undone. Freud believed these fixations shape personality and influence behaviour throughout adulthood.

Somewhere around the age of five, Freud proposed that children enter the phallic stage, marked by increasing social awareness. At this age, children begin to develop skills such as keeping secrets and expressing shame. Gender preferences also become more apparent, with boys and girls gravitating towards different types of play. Freud observed that children begin to show interest in their genitals at this stage, although his suggestion that this interest involves sexual pleasure remains highly contentious.

Freud’s theory also introduces the Oedipus Complex, which he saw as a defining moment in childhood development. Resolving this psychological conflict determines whether a child transitions into adulthood with a healthy, balanced personality. For Freud, early childhood is not simply a series of stages but a pivotal period where unresolved conflicts become fixations that persist and influence later life.

After this stage, children enter the latency stage, where sexual and instinctual drives become dormant, and the child focuses on hobbies, school, and friendships. Freud believed this apparent calm concealed the unconscious workings of unresolved issues, which would later emerge during adolescence.

ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT

Freud described adolescence as the culmination of psychosexual development. With the onset of puberty, the genital stage begins, marked by a renewed focus on the body and sexual pleasure. Adolescents who successfully resolve earlier conflicts will transition into healthy relationships marked by mature and balanced sexual interests. However, unresolved fixations or poorly developed defence mechanisms can lead to maladaptive behaviours, ranging from anxiety and obsession to troubled or exaggerated sexual relationships.

For Freud, adolescent development is the result of earlier experiences. The "cake," as he described it, has already been "baked," with the final stage merely revealing the results of childhood experiences and conflicts.

VARIATIONS IN THE TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY

The dominance of one component of Freud’s tripartite personality—id, ego, or superego—is shaped by early childhood experiences and the resolution of psychosexual stages:

Id Dominance: Overindulgence or lack of discipline in early childhood strengthens the id, leaving immediate gratification unchecked. A child accustomed to having all their desires fulfilled quickly may struggle with impulse control later in life.

Ego Dominance: Balanced and supportive parenting fosters a strong ego. When a child is guided to navigate their desires while understanding social and moral boundaries, they develop a rational and adaptive approach to decision-making.

Superego Dominance: Harsh or overly strict parenting can lead to an overdeveloped superego, as the child internalises rigid moral standards. This may cause excessive guilt, anxiety, or self-repression in adulthood.

APPLICATION OF THE TRIPARTITE PERSONALITY THEORY

SCENARIO: GWENDOLINE AND THE CHOCOLATE CAKE

Gwendoline enters the kitchen and sees her favourite chocolate cake on the table. No one else is home. Her response depends on which component of her personality—id, ego, or superego—is dominant.

ID DOMINANT

Gwendoline devours the entire cake without hesitation, ignoring that it belongs to someone else or the potential consequences for her health. The id drives her to seek immediate gratification from her craving, disregarding social or moral constraints.

POSSIBLE MANIFESTATIONS OF ID DOMINANCE

Anti-social personality disorder

Addiction (e.g., alcohol, drugs, gambling, shopping)

Obesity or binge eating

Violence or sexual crimes

Narcissistic personality disorder

Reckless behaviour (e.g., drunk driving or delinquency)

Psychopathy (anti-social traits)

Slothfulness

Delinquency

ABH (Actual Bodily Harm)

GBH (Grievous Bodily Harm)

Manslaughter

Drunk/drug driving

Gambling addiction

Promiscuity

Shopping addiction

Surgery addiction

EGO DOMINANT

Gwendoline eats a small slice of the cake and leaves a note apologising for taking it. Her ego mediates her craving for the cake with her understanding of the social and moral implications, allowing her to act in a balanced and ethical way.

POSSIBLE MANIFESTATIONS OF EGO DOMINANCE

Responsible decision-making

Ethical and balanced behaviour

SUPER EGO DOMINANT:

Gwendoline refrains entirely from eating the cake, as her superego considers it immoral to take what isn’t hers or indulge in unhealthy food. While this demonstrates restraint, excessive superego dominance can lead to unnecessary guilt or self-denial.

POSSIBLE MANIFESTATIONS OF SUPEREGO DOMINANCE

Anorexia Nervosa or obsessive dieting

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Hoarding

Anxiety

Phobias

Depression

PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder)

Body dysmorphia

Gender dysmorphia

Sexual dysfunction problems or inhibition

Inhibited self-harm

Social anxiety

Excessive focus on physical health and appearance (e.g., gym fanaticism or extreme dieting)

IMPLICATIONS

This scenario demonstrates how the dominance of one component in the tripartite personality influences decisions and behaviour. A balanced personality, where the ego mediates effectively between the id and superego, is essential for healthy functioning:

Id dominance results in impulsive and often destructive behaviours.

Superego dominance results in excessive rigidity, guilt, and self-criticism.

Ego dominance allows for balanced decisions but may lead to overcalculation, limiting spontaneity.

FACTUAL NOTE

While these applications align with Freud’s psychoanalytic framework, Freud does not explicitly identify the specific behavioural manifestations listed as speculative. Modern psychology critiques Freud’s lack of empirical evidence for direct links between the id, ego, superego dominance and specific personality traits.

EVALUATION OF THE PSYCHODYNAMIC APPROACH

ADVANTAGES

ADVANTAGES OF FREUDIAN THEORY

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory revolutionised psychology and psychiatry at a time when understanding the mind was still in its infancy. His ideas emerged during an era when psychiatry was often inhumane, with mental health treatments either non-existent or restricted to asylums with cruel and ineffective practices. Freud introduced a more compassionate and innovative approach, focusing on understanding the individual's psyche rather than dismissing or ostracising them.

BIZARRE CORRESPONDENCES WITH MODERN NEUROSCIENCE

While Freud’s theories are not strictly supported by modern neuroscience, intriguing parallels exist between his ideas and certain neurological findings. Libet’s 1980s research on unconscious decision-making revealed that decisions are initiated unconsciously before becoming conscious, aligning with Freud’s assertion that the unconscious mind is a driving force behind behaviour. Similarly, Freud’s tripartite model of the psyche—id, ego, and superego—loosely correlates with specific brain functions. The id resembles the amygdala, which is responsible for instinctual drives like aggression and fear. The ego aligns with the central executive functions of the prefrontal cortex, which mediate decision-making and balance reality. The superego reflects elements of the limbic system, which governs emotional regulation and internalised moral reasoning.

Freud’s emphasis on early childhood development also corresponds with experience-expectant plasticity in neuroscience, where early environmental input profoundly shapes brain organisation and development. While these correspondences do not validate Freud’s theories, they highlight how his ideas captured the essence of specific psychological and neurological principles.

RELEVANCE TO THE ZEITGEIST

Freud's theories resonated with the zeitgeist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries when direct examination of brain activity was impossible. Without neuroimaging or other advanced scientific tools, Freud’s focus on the unconscious mind, dreams, and early experiences provided a plausible framework for understanding behaviour. His approach aligned with the limitations of scientific knowledge at the time, offering a groundbreaking explanation for mental processes and disorders.

CONCEPTUAL AND CULTURAL LEGACY

Freud’s ideas have left an enduring influence that extends beyond psychology, shaping various fields and becoming part of everyday life. His defence mechanisms, such as repression and denial, remain cornerstones of psychological understanding. For instance, repression often appears in trauma cases like sexual abuse, where distressing memories are pushed into the unconscious to protect individuals from emotional overload. Denial, frequently observed in addiction, involves refusing to acknowledge the seriousness of one’s behaviour or its consequences.

Freudian theory has profoundly influenced literature, where critics explore unconscious motives in texts, and art, where symbolism and hidden drives inspire creativity. Terms like "Freudian slip," "ego," and "repression" are now ingrained in everyday language, demonstrating the widespread cultural impact of Freud’s ideas. Furthermore, Freud humanised psychiatry, replacing punitive treatments with psychoanalytic techniques that allowed individuals to explore their inner lives. These innovations laid the foundation for modern mental health therapy.

ENDURING RELEVANCE

Despite criticisms and occasional obsolescence, Freud’s ideas provide valuable insights into human behaviour. His recognition of the unconscious mind, defence mechanisms, and the interplay between instinct, morality, and rationality remains a cornerstone of psychological thought. His concepts' ongoing application and discussion in clinical and cultural contexts underscore their lasting significance.

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory bridged the gap between science, art, theory, and practice. While not without limitations, his work shaped modern psychology, psychiatry, and broader cultural understanding, leaving an enduring legacy that remains relevant today.

Critics of psychoanalysis have argued that it tends to cater to the affluent due to its high cost and time-consuming nature. Notably, it is typically not covered by publicly-funded healthcare systems like the NHS. Furthermore, many individuals undergoing psychoanalysis are not severely mentally ill, particularly in terms of psychotic conditions. Instead, they often seek treatment for the challenges posed by modern Western life, such as depression, anxiety, and contemporary existential concerns related to fidelity, inhibition, and other issues.

DISADVANTAGES

NOT A COMPREHENSIVE THEORY

A significant limitation of Freud’s psychodynamic theories is that they fail to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding human behaviours and mental processes. While the theories offer profound insights into mental illnesses and deviant behaviours, they neglect higher cognitive functions such as memory, attention, problem-solving, and intelligence. These areas are central to understanding the neurotypical brain, yet they remain largely unexplored in Freud’s work.

Freud focused heavily on the unconscious mind and early childhood experiences, so his theories often prioritise pathology over normal functioning. For example, while Freud’s concept of defence mechanisms explains how individuals cope with anxiety and stress, it does not address how people achieve growth, creativity, or cognitive mastery—critical elements of human development.

THE ROLE OF GENETICS

Another significant critique comes from behavioural geneticists like Robert Plomin, who argue that Freud sent society searching in the wrong direction for explanations of personality and behaviour. Freud’s theories heavily emphasised parenting and early environmental influences, suggesting that the treatment received during childhood determines adult behaviour. However, Plomin and other geneticists assert that heredity influences personality traits more than Freud acknowledged. The genes inherited from biological parents play a substantial role in shaping personality, intelligence, and temperament, overshadowing the deterministic influence of parenting styles proposed by Freud.

Modern research has provided strong evidence for the role of genetics in personality traits, such as extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, suggesting that the psychodynamic perspective undervalues the biological foundation of behaviour.

NARROW FOCUS ON DEVIANCE

One of the main appeals of psychodynamic theories is their ability to explain deviant behaviours and emotions. Freud’s theories delve into the unconscious processes and repressed conflicts that drive abnormal behaviour, offering valuable insights for understanding mental illnesses like neuroses, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. However, this narrow focus limits their applicability to explaining normative behaviour. While psychodynamic theories excel at describing why some behaviours deviate from the norm, they offer less insight into how people learn, adapt, and thrive in everyday life.

BALANCE OF CRITICISMS AND CONTRIBUTIONS

While Freud’s psychodynamic theories are undoubtedly foundational and influential, their lack of comprehensiveness poses a challenge to the modern understanding of psychology. Contemporary approaches, such as cognitive-behavioural theories and neuropsychology, have filled many of the gaps left by Freud by exploring areas like memory, executive functioning, and the biological basis of behaviour. However, Freud’s emphasis on the unconscious mind and early experiences remains an essential part of the conversation in psychology, especially in understanding deviance and mental health challenges.

CULTURAL AND TEMPORAL BOUNDARIES:

Critics argue that psychodynamic theory is constrained by the cultural and historical context in which it was developed, reducing its relevance in modern and diverse cultural settings. Freud's work emerged in an era of repressive attitudes toward emotions and sexuality, particularly in Europe and the USA, where his ideas gained significant traction. Many of the theory’s concepts and interpretations were shaped by the cultural norms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Freud’s research predominantly focused on middle-aged Viennese women, a demographic characterised by emotional repression and conservative views on sexuality. This limited sample raises questions about the applicability of his theories to broader, more diverse populations. By centring his case studies on this narrow group, Freud may have created a less relevant framework for individuals outside this specific cultural and social milieu.

Since Freud's time, cultural and social norms have evolved significantly, particularly regarding openness about emotions and sexuality. These shifts challenge the universality of Freud's assumptions and interpretations, rendering some of his work less relevant in contemporary society. Psychodynamic theory's historical and cultural specificity highlights its limitations when applied to modern, global, and culturally diverse contexts.

ADAPTATION CHALLENGES:

The psychodynamic approach’s rigidity in adhering to its foundational principles can make it challenging to adapt to individuals' changing needs, values, and beliefs across diverse cultural backgrounds and periods. For instance, Freud’s emphasis on the Oedipus Complex, rooted in early 20th-century European family structures, may not resonate with cultures prioritising collectivism or having different familial dynamics. In such contexts, the theory's focus on individualistic nuclear family models can feel out of place, reducing its relevance and effectiveness. This highlights the need for more flexible and culturally sensitive adaptations of psychodynamic principles.

FREUD'S OEDIPUS COMPLEX AND SINGLE-MOTHER HOUSEHOLDS

Freud’s theory of the Oedipus Complex emphasises the presence of both a same-sex and opposite-sex parent during psychosexual development. According to Freud, a boy resolves unconscious feelings of desire for his mother and rivalry with his father by identifying with the father, which helps develop the superego and manage internal conflicts. However, Freud’s framework presumes this traditional dynamic, making it challenging to apply in non-traditional family settings, such as single-mother households.

In single-mother households, the absence of a father figure complicates Freud’s model. Critics argue that this absence challenges the universality of Freud’s theory, as it assumes the necessity of both parental roles for healthy psychosexual development. Some psychoanalysts have proposed that boys in these households may transfer their rivalrous feelings to other male figures, such as uncles, teachers, or community role models. However, this adaptation deviates from Freud’s original theory and raises questions about its applicability in diverse family structures.

MISOGYNISTIC

The psychodynamic approach has faced criticism for its historical bias towards females. Freud's belief in concepts like penis envy and the resulting idea of female inferiority have been contentious points of contention. According to Freud, females were considered inferior to males because of their supposed penis envy. He also suggested that females tended to develop weaker superegos and were more prone to anxiety due to their inability to go through the Oedipus complex, which was seen as a male-oriented concept.

Psychologist Karen Horney challenged Freud's theories, labelling them as inaccurate and demeaning to women. Horney proposed an alternative perspective, suggesting that men experience feelings of inferiority because they cannot give birth to children, a concept she termed "womb envy."

Supporters of Freud argue that he was not necessarily misogynistic but rather reflected the prevailing societal norms and attitudes of his time. During the 19th century, women were indeed treated as second-class citizens. Men enjoyed legal, social, educational, and economic advantages over women. In this context, the penis symbolized not just physical attributes but also the power and freedom that men possessed.

In the 1800s, women faced severe limitations in terms of rights and opportunities. They could not vote, work in many professions, own property, or inherit titles. Financial independence was challenging unless they received an inheritance from a wealthy father or became widows. Women needed to secure advantageous marriages for financial security because there was no welfare state to provide support. The limited options available to women during this era help explain why they might have envied the social and economic advantages men enjoyed.

SOCIALLY SENSITIVE RESEARCH

Freud's theory has been criticised for its social sensitivity, particularly for the potential harm it may cause by blaming parents, especially mothers, for their child's deviant behaviour. Such blame could lead to these parents being stigmatised and marginalised in society. It raises the question of why mothers are consistently singled out for blame. Research has proved that mothers are not solely responsible for shaping their children's personalities (Neill, 1990).

The idea that mothers are to blame for their children's mental health issues, as suggested by the schizophrenogenic mother theory, may be rooted in the fact that females traditionally take on the bulk of child-rearing responsibilities. However, this assumption doesn't hold up under scrutiny. Psychoanalytic theories often carry misogynistic assumptions, as most mothers of schizophrenic individuals do not fit the stereotype of being harsh and withholding, as assumed by Fromme-Reichman.

Research by Waring and Rick (1965) found that mothers of mentally fragile children tended to exhibit traits such as anxiety, shyness, and withdrawal. These traits might be reflective of the tremendous stress and challenges associated with raising a child with a severe mental disorder. Therefore, it is essential to recognise that blaming mothers or parents in general for their child's mental health issues is an oversimplification that can lead to unjust blame and ignores the complex interplay of various factors in a child's development.

NEO FREUDIANS (PSYCHODYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE:

In contrast to the emphasis on sexuality in psychoanalysis, the psychodynamic)

This perspective places greater importance on the role of the social environment in shaping one's personality and behaviour.

Critics of Freud's theory argue that his work is more applicable to men and that it places excessive emphasis on early childhood and sexuality. Neo-Freudians represent a group of thinkers who diverge from Freud's perspective. They reject the notion that personality development is completed by age six and instead propose that it continues throughout the lifespan. Neo-Freudians have expanded upon Freud's ideas, incorporating a more significant influence from the environment and emphasising the significance of conscious thought alongside the unconscious. They have also downplayed the centrality of sexuality and the Oedipus complex in their theories.

Key figures in this neo-Freudian movement include Erik Erikson, known for his work on psychosocial development, Anna Freud, Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, Karen Horney, and proponents of the object relations school of thought. These thinkers have enriched and evolved Freudian ideas to create a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of human development and personality.

A notable critique of Freud's theory is its heavy focus on early childhood, neglecting later stages of development, such as the Latency Stage and significant growth during adulthood. Erik Erikson, a follower who revised Freud’s ideas, proposed a broader developmental framework. Erikson argued that humans experience more than Freud's five stages, extending into old age. According to Erikson, each stage is characterised by a specific crisis that individuals must resolve. For instance, Erikson suggested that newborns face a conflict between developing trust in caregivers and feeling fear or mistrust toward them.

A more significant criticism comes from American author Jeffrey Masson (1984), who examined Freud's files and diaries. Masson contends that Freud's patients were victims of childhood sexual abuse, a fact Freud allegedly recognised but chose to obscure. Masson theorised that Freud introduced the Oedipus Complex as a less disturbing alternative, suggesting that children harbour sexual fantasies about their parents rather than having endured actual abuse. While Masson’s claims are highly controversial, if true, they undermine the credibility of Freud's theory of the Oedipus Complex.

DETERMINISTIC

Determinism in psychodynamic theories is evident in the sense that individuals are seen as having no control over the development of fixations, which are shaped by early family experiences. According to Freud, all thoughts, behaviours, and emotions are determined by these childhood experiences. While this perspective does not attribute these determinants to an individual's biology or free will, it still reflects a form of determinism.

The deterministic nature of psychodynamic theories can be seen as both positive and negative. On the positive side, it highlights the importance of understanding how expressed emotions can influence the exacerbation of symptoms of conditions like psychosis. However, on the negative side, it can lead to blame and guilt, particularly towards parents, as individuals may feel responsible for their fixations. Furthermore, this deterministic view may suggest limited personal agency or free will over one's behaviour, which can be seen as disheartening.

REDUCTIONIST

Psychodynamic explanations tend to be reductionist as they simplify the complex process of personality formation, primarily attributing it to early childhood trauma and personality issues. However, evidence from studies involving both identical (MZ) and non-identical (DZ) twins suggests that biology also plays a significant role in shaping an individual's character and personality.

Adopting an eclectic approach that considers a broad range of factors, including biological and environmental influences, is crucial to gain a more comprehensive understanding of personality development. Such an approach recognizes that personality is a complex interplay of various elements, and no single explanation can fully account for its complexity. By incorporating multiple perspectives, we can better understand how personality is formed and how it develops over time.

IS PSYCHOLOGY A SCIENCE?

Psychodynamic theories heavily rely on evidence from Freud's case studies, such as those of Little Hans and Anna O. However, the case study method has its limitations, one of which is susceptibility to researcher bias. In some instances, re-examinations of Freud's clinical work have indicated that he may have distorted his patients' case histories to make them align more closely with his theoretical framework (Sulloway, 1991).

Additionally, case studies are typically focused on in-depth examinations of individual cases. This narrow focus can make it challenging to generalize findings to the broader population, as one person's experiences and behaviours may not represent the entire world. Consequently, while case studies provide valuable insights, they should be complemented by other research methods to establish more robust and widely applicable conclusions in psychology.

NOMOTHETIC, IDIOGRAPHIC OR BOTH?

Freud's theory is nomothetic, as it aims to establish general principles and explanations that apply to all individuals. However, it's important to note that the research methods often used to explore and validate Freud's theory, such as case studies, tend to be more idiographic in practice.

Case studies involve the in-depth examination of individual cases to gain a comprehensive understanding of specific phenomena. While this method is idiographic, focusing on unique cases, it is used to gather evidence and support broader nomothetic claims or theories.

So, while there may appear to be a paradox in the research approach, it's common in psychology to use idiographic methods to contribute to our understanding of nomothetic principles. These different research approaches can complement each other, providing a more comprehensive view of psychological phenomena.

OPERATIONALISING FREUD’S KEY TERMS

One of the significant challenges with Freud's psychodynamic theories is the difficulty in operationalizing and measuring many of the concepts he introduced. Concepts like the id, ego, superego, unconscious processes, and ego defence mechanisms are abstract and not easily quantifiable. This lack of measurability makes it challenging to subject these concepts to empirical testing using the scientific methods typically employed in psychology.

In modern psychology, there is an emphasis on operationalising variables and using quantitative methods to test hypotheses and theories rigorously. While influential in shaping psychology, Freud's theories do not always align with these empirical and measurable standards. This has led to criticism and debate within the field regarding the scientific validity of his work.

FALSIFICATION ISSUES

Karl Popper's critique of Freud's theories, particularly in scientific falsifiability, is a significant aspect of the psychoanalysis debate. Popper argued that for a theory to be considered scientific, it must be falsifiable, meaning there should be a way to test it rigorously and potentially prove it wrong. According to Popper, Freud's psychoanalytic theories lacked this essential criterion because they could be interpreted so that they would always appear to be confirmed, regardless of the data.

HERE IS A SCENARIO TO ILLUSTRATE THIS POINT

Pete has battled depression for two decades, seeking the assistance of a psychoanalytic therapist without improvement. He feels worse than ever and accuses his therapist of deception, asserting that there is nothing hidden in his unconscious. Pete dismisses the theory as psychobabble, citing his happy childhood as evidence.

The therapist, in contrast, disagrees and contends that the root cause of Pete's depression is so deeply buried in his unconscious mind that it eludes conscious awareness. Pete dismisses this notion as nonsense, and a debate ensues. The question arises: can Pete provide evidence to disprove the therapist's claim?

According to Popper's criterion, for a theory to be considered scientific, it must have the potential to be proven wrong or falsified. In this scenario, Pete challenges the therapist to produce evidence that substantiates the existence of these deeply buried, painful experiences within his unconscious mind. If Pete can demonstrate the absence of such evidence, he would argue that psychoanalysis lacks falsifiability and does not meet the criteria for scientific status.

Popper drew a sharp distinction between theories like Einstein's theory of relativity, which could make precise predictions that could be empirically tested and either verified or refuted through experimentation and Freud's psychoanalysis, which relied on interpreting past experiences. Popper's critique centred on psychoanalysis's retrospective and subjective nature, where past events and experiences could be reinterpreted to fit the theory.

To illustrate this issue further, consider the following example: Freud's psychoanalytic framework could offer explanations for an individual's sexual inhibition based on two contradictory scenarios. On one hand, it could attribute the inhibition to insufficient affection during childhood, while on the other hand, it could attribute it to excessive affection during childhood. This apparent flexibility within Freud's framework made it exceedingly challenging to subject his theories to empirical testing in a manner that could potentially disprove them. This adaptability allowed Freud to interpret data in ways that supported his theories rather than subjecting them to rigorous empirical scrutiny.

RECENT ADVANCES IN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Cognitive psychology has made significant strides in identifying unconscious processes, including procedural memory (Tulving, 1972), automatic processing (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999; Stroop, 1935), and social psychology has highlighted the importance of implicit processing (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). These empirical findings have underscored the significance of unconscious processes in shaping human behaviour.

Kline (1989) has argued that psychodynamic theory consists of a series of hypotheses, some of which are more amenable to testing than others and some with more robust supporting evidence than others. While it is true that certain aspects of psychodynamic theories may not lend themselves easily to empirical testing, this does not diminish their explanatory power or preclude the possibility of testing them in the future. The evolving landscape of psychology may provide opportunities for further exploration and verification of psychodynamic concepts as our methodologies and understanding continue to advance.

HOMOPHOBIA?

Freud's theories, particularly the phallic stage and the Oedipus conflict, have faced criticism for their potential to perpetuate homophobic ideas. It was theorised that males who could not successfully identify with their fathers might develop homosexual orientations, implying that homosexuality could be attributed to a fixation. However, this perspective has been widely discredited, as it does not align with contemporary understandings of human sexuality.

Furthermore, Freud's assertion on this matter has been proven incorrect by the countless heterosexual adult males raised by single-parent mothers. Modern understandings of sexual orientation recognize that it is not determined by early childhood experiences or the gender of one's primary caregiver. Sexual orientation is a complex and multifaceted aspect of human identity that cannot be reduced to simplistic explanations like those proposed by Freud. It's essential to approach the topic of sexual orientation with sensitivity, respect for diversity, and an understanding of the complexities involved.

PSYCHOANALYSIS

Psychoanalysis, commonly known as the talking cure, is a psychological theory and therapeutic approach developed by Sigmund Freud. The fundamental premise of this theory is to bring unconscious elements into conscious awareness. According to Freud, this process enables individuals to overcome psychological issues rooted in their unconscious mind, ultimately leading to the cessation of maladaptive behaviour.

Psychoanalysts undergo extensive training, including their own experience with psychoanalysis, to develop the necessary skills to decode the symbolic meanings embedded within patients' language, dreams, fantasies, wishes, and desires.