Are Stereotypes Inevitable?

INTRODUCTION

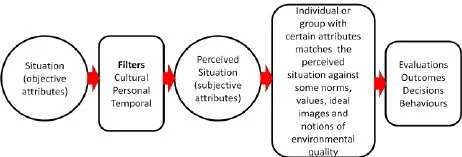

During every moment of a human's life, huge volumes of sensory information, continually bombard the brain. But only a fraction of this sensory information can be taken in by sensory receptors and processed by the nervous system, as there is limited space.

Exercise 2 Let’s take part in a brief exercise:?Just for a few moments, try to be mindful of the place you are in. Contemplate all your senses one by one and pause for a minute and think about what you hear, feel, etc.?

When you were focused on paying attention, you might have picked up on parts of your environment that you did not pay any consideration to before. I don’t know what, but maybe, for example, you could have noticed a conversation or sound you had blocked out.

I bet your extended focus never included how your bottom felt on the chair you are sitting on right now. I guess this is because monitoring how your bottom feels is not a priority, as another input is more important (unless the chair had a pin on it). You can’t be cognisant of all the sensory input that infiltrates your brain every nanosecond of your every conscious moment; something has to give; your brain can only pay attention to the highlights of its environment, it will blank the rest out.

Thus, we can pick out a juicy conversation in a loud room, we can spot a mate in a crowd and we can swerve the fox that darted across the road. Somehow, even with vast sums of data submerging our senses, we’re able to focus on what’s important and act on it but exclude a lot of maybe (ir)relevant stuff. Attentional processes are the brain’s way of directing a spotlight on significant events and filtering out anything in the periphery. Perception serves the present because we need to have a representation of the world so we can engage with it.

Exercise 2 Let’s do another quick exercise to see how much you focus. For example, you use money all the time, right but can you draw a five-pound note/dollar bill; try it?

I bet the majority of people that tried this failed abysmally.

THE BRAIN IS A COGNITIVE MISER This failure to replicate the £5 note reveals that you have never, focused on its detail as it was only processed in outline. This exercise demonstrates that your brain doesn’t even deeply process things you use every day, like currency

The brain needs to speculate on its feet because by the moment you have worked out whether the “slippery” looking character who appears to be pursuing you in the park is a coincidence or dodgy you might die or get mugged. You might too feel like a complete git for forming such assumptions when you realise this individual is a park keeper doing litter duty. We are all guilty of “jumping the gun”, maybe these blunders get noted and the stereotype gets weakened or altered, maybe it doesn’t; continuing to be “street-wise” can’t be a bad thing but sticking to the idea that all French people wear a string of onions around their neck when you have encountered otherwise is plainly cognitive dissonance.

By the way, the above point reminds me of a quote by Martin Vagner in the film “The girl with the dragon”,

“Let me ask you something? Why don’t people trust their instincts? They sense something is wrong, someone is walking too close behind them... You knew something was wrong, but you came back into the house. Did I force you, did I drag you in? No. All I had to do was offer you a drink. It’s hard to believe that the fear of offending can be stronger than the fear of pain. “

But you cannot over analyse everything you perceive, as present perceptions will very quickly become the past. And if you stayed too long analysing past perceptions, you wouldn’t be able to process your ever-changing new present. Your perceptions would soon have a backlog and no continuity.

SCHEMATA AND STEREOTYPES

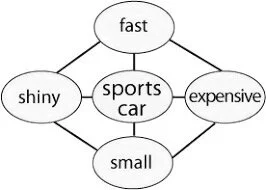

Our brain needs to organise information into meaningful patterns so it doesn’t become bewildered. To do this, the brain uses biases or more specifically schemata and stereotypes to navigate this sensory data. In psychology, a schema describes a pattern of thought or behaviour that organises categories of information and the relationships among them so we don’t have to continually assess a person, place or thing etc. in other words, it organises this data into mental shortcuts so that our world is simplified.

Mental shortcuts make it faster and easier for the brain to sort through the overwhelming and relentless data it encounters. Recording only a sketch version for most of what it greets, is just good housekeeping, or conservation; this is why you have never known a £5 beyond a basic representation and why you almost certainly use stereotypes. The brain creates only a few rules for unimportant or rarely encountered stimuli and moves on.

HOW SCHEMATA DEVELOP

The easiest way to understand how schemata develop is to get you to imagine that you are an infant engaging with the outside world for the first time. Let’s pretend you are in the back garden (yard) with your parents. Your understanding of the world will be limited. You won’t be able to understand where one object begins and another ends. You don’t know the names of anything, how they smell, what they do, how they would feel if you grasped them etc.

This is because infants are born without any knowledge and they initially interact with their world by seeing, touching and mouthing then they start to form basic schemata (categories) of these experiences. For example, assumptions about what soft things look like, or the etics of their language, will be based on their cultural experience, parenting, and media influences.

The first six months of a baby’s brain development are crucial, they will literally wire up neural connections to everything they encounter and look for patterns and associations in order to make sense of their complicated world. As infants grow, they begin to modify their schemata and further divide objects into the more complex schema. An example is below:

ACCOMMODATION AND ASSIMILATION

Let's say that Mary is a toddler who has a golden retriever, named Frank. One day, Mary stays at her uncle’s house who has just bought a new Dachshund. Even though this new dog looks quite unlike Frank, Mary still sees that the Dachshund is also a dog. Mary put the new object – her uncle’s Dachshund -- into an already established category -- 'dog.' Piaget called this assimilation. Let's say Mary now visits her grandma, who has a rabbit. Mary points at the rabbit and says 'dog!' Her concept of dog, which successfully included both Frank and her uncle’s Dachshund, is too wide; she calls anything that has four legs and whiskers a 'dog.' Her mother explains that this is a 'rabbit,' and Mary alters her schema of 'dog' correspondingly

CAN WE EXIST WITHOUT SCHEMATA AND STEREOTYPES? But stereotypes rightly have very bad press, Years of research have shown that stereotypes can accelerate intergroup antagonism and cause discrimination around, race, gender and numerous other social differences. Stereotypes are often used to validate injustice and oppression.

The fact that stereotypes are often detrimental does not mean that they are purely processing malfunctions—malware in our processors and therefore untrue. The impulse to stereotype is not a cultural innovation, like fashion, but a species-wide adaptation, like language. Everyone does it.

It's irrational to say the use of stereotypes could be suppressed as we would be incapacitated by their loss. We couldn’t function because we would be lost in a confusing world where categories of people and objects didn’t exist. We’d end up ignoring situations like a lone toddler wandering the streets at night because there’d be no generalisation applicable to their age and capabilities!

If I told you my parent’s friend was visiting from Jamaica, you might be surprised if they introduced you to a 21-year-old, Chinese-looking, goth. You were expecting, an elderly black person who liked reggae based on your experience, history and geographical knowledge.

Similarly, if I asked you what type of person a kolpat was, you would have no idea (as they don’t exist) but your brain would search for matches so something could represent this category. If I then told you Kolpats came from western Europe you’d probably assume they had dark hair and tanned skin because of the law of averages.

ARE ALL STEREOTYPES BAD? Some stereotypes are clearly more harmless and helpful than others but why shouldn’t we disapprove of religions if we are atheists or prefer some ideology over another? Why shouldn’t we justify our preferences or openly rate some belief over another? We should be able to disagree courteously, and most importantly, we should be able to change our minds?

Moreover, the fact that many stereotyped group differences exist and that biology (age, IQ, disability, gender) plays a role in their existence does not determine how society should treat them. Society can increase, help or hinder a group difference this is why groups often form groups based on their identity (identity-politics) so their observed differences can be attended to justly.

But some stereotypes are more insidious, for example, people can reveal some very crass assumptions, “You don’t dance very well for a Jamaican person, you don’t drink a lot for a Scottish person, or worse of all, you are not like other - delete as appropriate - black people, girls, boys, lesbians, old people, Muslims.

What people are usually communicating when they make such vacuous assumptions, is that they have lived a sheltered life and their schemata are based on hearsay and COD science. So when they meet a *German person who doesn’t like sausages or steal towels, they think it’s because the person is an exception to their stereotype and not the other way around.

ARE GENERALISATIONS UNAVOIDABLE But unfortunately, we have made horrible miscalculations, at one time or another about somebody based on a variable we didn’t consider. We can’t be expected to know the customs, mores and norms of every culture. But hopefully, most of us can have the best of intentions and know that there is a difference between admitting you are ignorant and acting on those assumptions.

I only recently changed the schema I had of Ethiopia (which was ruined by “Band-Aid” in the 1980s) from a land of starving people to what a groovy place to visit, this was only made possible after watching The Misadventures of Romesh Ranganathan., where they discussed how annoying people like myself. were If I’d met an Ethiopian person before watching Romesh, my brain wouldn’t have been able to resist the urge to rely on some of my outdated information - if only because there has to be some level of representation for a concept to exist.

What do you do if you meet someone you think might be categorisable to some extent, for example, a Jewish or Muslim person, should you be allowed to assume some basics, e.g., they probably won’t eat pork and ask away or should you talk cagily, until clues are revealed to avoid offence?

WHAT IS OFFENSIVE? The trouble with assuming a moral perspective is that it can also be based on a stereotype, so if you decide to refer to what appears to be a female, as non-binary, you might find she is enraged because this particular female deplores the eradication of binary labels. What constitutes an offence is subjective after all and nobody has the right to decide what the consensus on offence is.

IN GROUPS, OUTGROUPS, EVOLUTION AND STEREOTYPING The mechanics of prejudice are incredibly complicated but some would argue that some form of negative bias is inevitable. For example, some researchers suggest “the mere existence of group categories (identity-politics, cultures and subcultures basically) creates prejudice”. Proponents of this view might draw on many arguments. In terms of securing resources and safety they’d say it’s rational for people to act selfishly or in their family’s interests? Some people would argue that, from an evolutionary standpoint, stereotyping has been naturally selected so that people can defend their genetic heritage as preferring their own groups, be that their culture, religion, family, or nationality would be a priority.

The suffocating stereotypes around racial categories, have no defensible biological basis. Children learn racial bias because they are passed down or learnt vicariously not because they are biologically relevant. But humans are programmed from their ancestral environments to be xenophobic especially in times of economic uncertainty, and they will narrow the parameters of who can be in their group as the resources get more scarce or they look for a scapegoat that is not part of their in-group, which is the story behind all genocide. Appearance and customs are obvious markers that someone is not your clan.

STEREOTYPES BASED ON BIOLOGY? It is short-sighted to totally refute our DNA, the fact that males and females are to some extent wired up differently suggests behaviour and capabilities might be predictable, up to a point., men have slight advantages in spatial processing for example and strength. Old people are generally physically and cognitively less robust etc. Can we really keep pretending, for example, that criminal behaviour, from petty theft to violent sexual attacks, are not overwhelmingly and universally committed by men!

HOW DO YOU MEASURE STEREOTYPES? But then although some stereotypes may be statistically more likely such as old people have a poorer memory recall, they will never all be universally valid because there will be old people that have superior working memory. Some would argue that unless stereotype is universally valid, we shouldn't make decisions affecting an individual based on a stereotype. So, for example, if a person wants to write an article that relies on the generalisation that males are at a higher risk of suicide in middle age, a rebuttal could be, “What about the men who don't fit this stereotype?”

But it's one thing to question a generalisation as wrong or to suggest a different generalisation for use in a particular context. It's quite another to say we should ignore all generalisations because there are exceptions to them.

Measuring stereotype accuracy in the real world is not easy. First, we have to agree on what percentage represents accuracy. Moreover, we also need to agree on what represents a "stereotype." In other words, when does something become factual, like most men are taller than women

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN APPROPRIATE AND NON-APPROPRIATE STEREOTYPES?

Age requirements. Most accept that a person should be a certain age to do certain things: vote, drive a car, get married etc. Neither is based on universally valid generalisations: Some 30-year-olds shouldn't get live alone and some 14-year-olds would be mature enough to do so. Some 12-year-olds could drive a car well.

Our brain’s architecture makes it inevitable that we will use stereotypes of social groups in order to navigate our social world because the values, mores, and beliefs that are entrenched in culture allow us to understand the world. We simply cannot exist without making assumptions. To forsake stereotypes would be like attempting to reject language and speak instead in Morse code, would you really have no objections to say your daughter dating a man in his 90s, would you offer a child a spliff?

REDUCING PREJUDICE

Many scientists who might agree with any of the arguments above would also agree that, nevertheless, we should do all we can to reduce inequality, and eliminate racism based on group membership. But isn’t this like saying ‘all people’s hearts eventually stop beating, but we really wished they didn’t? If research findings are leading us toward the view that prejudice is inevitable, should we really try to work against human nature?

Stereotypes are an integrated and reciprocally determined mix of both nature and nurture. For example, biological, views on stereotypes can only be appreciated in social frameworks, using socially created concepts, such as the notion of “stereotype.” To the extent that stereotypes are created by social constructions, we need to look to the environment, culture, identity politics, customs, mores, norms, values, beliefs, and media representations.

In summary, the harm caused by stereotypes is due to an increasingly difficult fit between age-old adaptations and the present social climate.

When this logic is applied to stereotypes, you can see that such generalisations evolved in a time when a clan was the defining unit of uniqueness. Today, in the zeitgeist of the individual, group, similarities, however valid may not always provide suitable cues for the modern world as we are experiencing swift social change that is making some group and gender stereotypes redundant and outdated.

For example, in our ancestral past, physical strength was a social asset as it increased survival chances. But this then slowly evolved to support a social system of male dominance But, in modern individualistic countries, many of these gender stereotypes are no longer relevant, the strongest don’t always become the most successful. The old stereotype that women are physically weaker is still accurate, but the right question in our new social times might be: Who cares?

MOVING FORWARD Paradoxical as it may appear, in order to counter racism, we need to recognise that the answer is not to quash our biology, but to use it more successfully and to better appreciate how people's interactions and culture create frameworks for their behaviour towards their own and other groups.

We also need to teach people about how their minds work from an early age. When people are taught about how their brains organise information, they are able to be more flexible with their allegiance to a stereotype because they know it may be an unreliable assumption! In other words, they are more likely to be accommodating and assimilate their schemata in line with new information because they are open to the idea their schemata and stereotypes are faulty.