LABORATORY EXPERIMENTS

TYPES OF EXPERIMENT

LABORATORY, FIELD EXPERIMENTS, NATURAL AND QUASI-EXPERIMENTS

Laboratory, field, natural and quasi-experiments all investigate relationships between variables by comparing groups of scores. Still, there are also significant differences between different types of experiments, such as how respected they are.

Laboratory experiments fulfil all the criteria of an actual experiment but have problems with external validity.

Field experiments are true but don't occur in a controlled environment or have random allocation of participants.

Natural and quasi-experiments cannot prove or disprove causation with the same confidence as a lab experiment.

Natural experiments don't manipulate the IV; they observe changes in a naturally occurring IV.

Quasi-experiments don't randomly allocate participants to conditions.

LABORATORY EXPERIMENTS

DEFINITION: "A lab experiment is the 'classic' experiment with all four features of a true experiment. Its strength comes from its "lab setting" which is a controlled environment. A laboratory setting doesn't have to be a laboratory with test tubes and scientific gizmos; it could be conducted in a field. However, any experiment in a special, tightly controlled environment is a laboratory. A laboratory setting is an environment where the researcher controls everything that happens. So if you close your classroom door with a sign outside saying "DO NOT ENTER: EXPERIMENT IN PROGRESS", you've turned your classroom into a psychology lab. Of course, there might still be a fire alarm or another interruption. However, many extraneous variables are ruled out in a lab setting. The hallmark of a lab experiment is that participants are aware of their involvement in the experiment.

In summary, the Solomon Asch study exemplifies a lab experiment where participants are aware of being part of an experiment. In contrast, the weapon focus study represents a field experiment where participants' behaviour is observed in a more naturalistic setting without their explicit awareness of being studied.

Laboratory experiments can include animals as they offer greater experimental control opportunities than research with humans.

ADVANTAGES: Lab experiments offer precise control over variables, minimizing extraneous influences and facilitating the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships, which is particularly advantageous in psychology research. For example, in a lab experiment investigating the effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive function, researchers can carefully manipulate the duration and quality of sleep participants receive, allowing for a clear understanding of how sleep affects various aspects of cognition without confounding variables from the external environment—facilitating the establishment of causal relationships. Researchers can meticulously manage all variables, enhancing the ease of replication and bolstering the reliability of study findings. Replication allows researchers to verify the results of a study. When multiple independent studies produce similar results, it increases confidence in the reliability and validity of the findings.

DISADVANTAGES:

THREATS TO THE EXTERNAL VALIDITY OF LABORATORY EXPERIMENTS:

Lab experiments may lack mundane realism, as the controlled environment may not faithfully replicate real-world conditions, potentially compromising ecological validity.

It's essential to recognize the difference between mundane realism and ecological validity in psychological research:

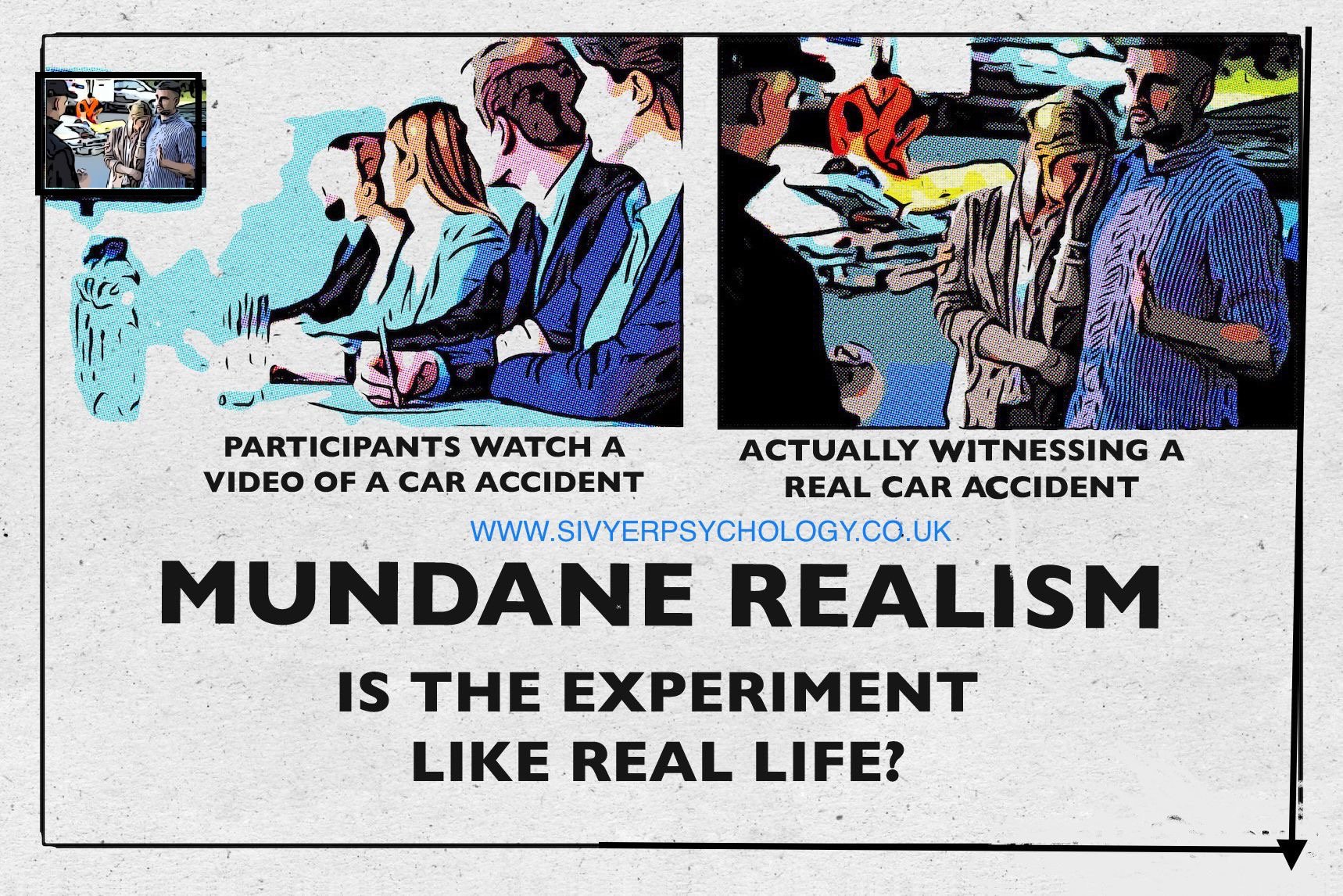

Mundane Realism: This term refers to the extent to which the conditions in a study resemble real-life situations. An example where mundane realism is questioned is Stanley Milgram's obedience study, as a teacher would never be asked to administer electric shocks to a student in real life, especially for minor errors. Another example is memory research, such as studies on digit span. Remembering random, nonsensical sequences of digits isn't a common real-life task.

Although researchers designing laboratory experiments try to create situations applicable to real life, they are often artificial to how the behaviour occurs. Take, for example, the Loftus study on eyewitness testimony. The participants in this experiment were shown videos of a car crash and then asked to make decisions based on what they saw. But there is a lot of difference between seeing a video of a car crash and seeing an actual car crash; the experimental version has the participants seated comfortably and with full attention intact. But seeing a real-life car crash will likely provoke a full fight/flight response and fractured attention.

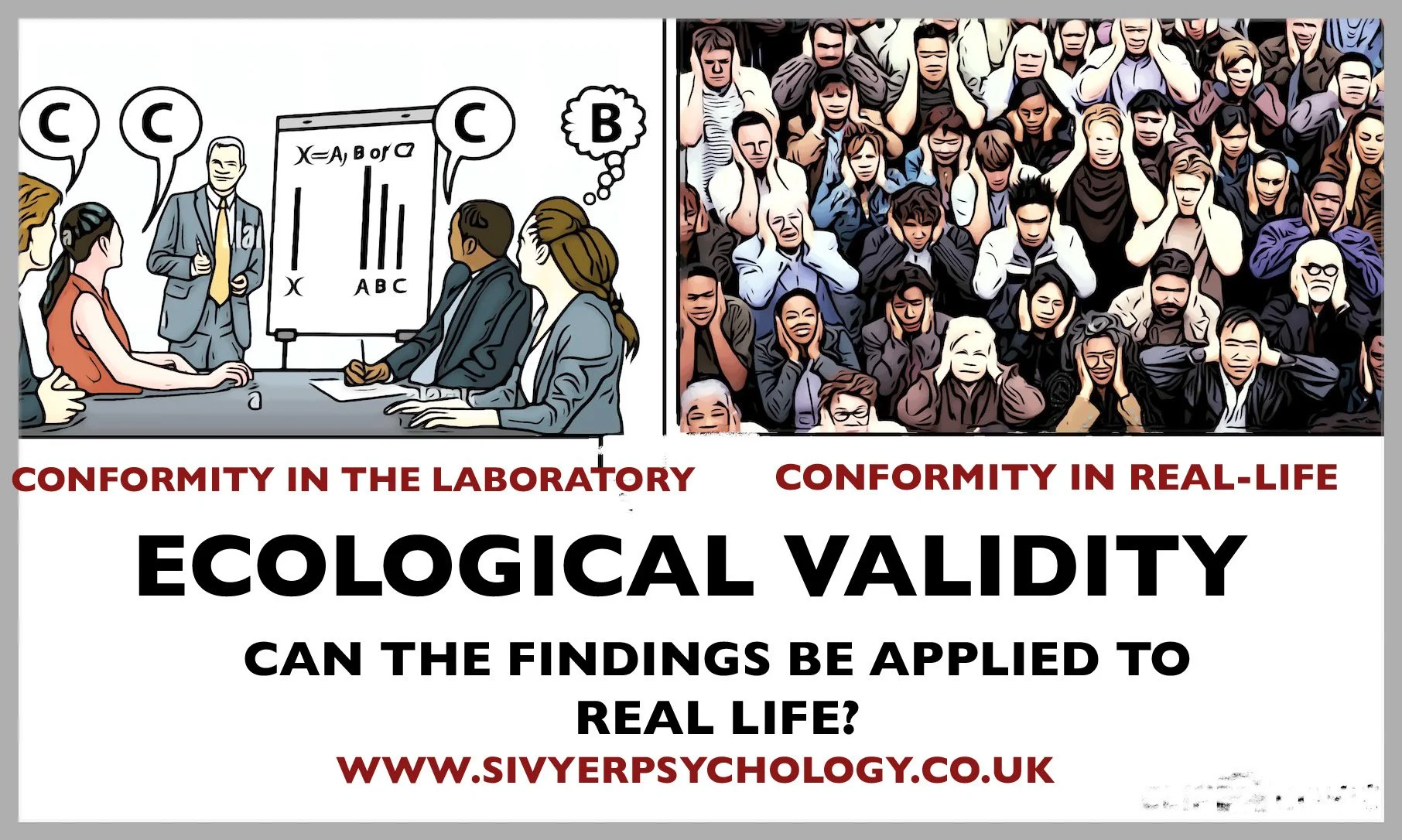

Ecological Validity: This concept involves the applicability of a study's results across different environments and settings. Just because a study does not have mundane realism does not mean it can't be applied to real life; it might still have ecological validity. In the case of the digit span example, most people struggle to remember long cell phone numbers, typically exceeding the 7±2 digit span limit identified in the research. This demonstrates the ecological validity of the findings despite the lack of mundane realism in the experimental task.

Ecological validity can be challenging in lab experiments when researchers cannot manipulate the variables they want to investigate. For instance, Stanley Milgram initially sought to explore the dynamics of atrocities like those seen in the Holocaust. However, he couldn't ethically manipulate participants to engage in actual violence. Consequently, he devised the electric shock experiment as a substitute, aiming for its findings to reflect real-world behaviour. Despite the controlled lab environment, Milgram believed his study could provide insights applicable to real-life situations, showcasing ecological validity.

However, Milgram's study lacked both mundane realism and ecological validity. While one of Milgram's variations showed how obedience levels dropped when the learner and the teacher were in the same room, the case of Milgram's study lacked both mundane realism and ecological validity. While one of Milgram's variations showed how obedience levels dropped when the learner and the teacher were in the same room, it did not accurately reflect real-life dynamics. Additionally, the study's applicability to events like the Holocaust was questioned. In real-life scenarios, SS soldiers often shot their victims even when they were nearby, and their obedience to authority persisted even in dire circumstances, which was not adequately captured in Milgram's study.

In conclusion, while a study may lack mundane realism, it can still possess ecological validity and vice versa. Both concepts are integral to understanding the external validity of research, allowing us to apply findings to broader contexts, such as different cultures, locations, populations, and settings.

THREATS TO THE INTERNAL VALIDITY OF LABORATORY EXPERIMENTS: Participant awareness of being in an experiment can trigger demand characteristics, social desirability bias, and the Hawthorne effect, influencing participant behaviour and threatening internal validity.

DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS: These are cues or hints within the experimental context that suggest to participants how they are expected to behave. When participants become aware of these cues, they may alter their behaviour to align with what they believe the experimenter wants or expects rather than behaving naturally. For example, in a lab study investigating the effects of caffeine on cognitive performance, participants who know they are receiving caffeine might consciously try to perform better to confirm the hypothesis.

Demand characteristics might include the following behaviour:

Acting nervous or out of character because they feel they are being evaluated in some way because they are in an experiment.

Sometimes, if participants are in both conditions, they can guess what the experiment is about and, as a result, behave differently.

Or it could be that they guess what the researcher wants to happen in the experiment and try to please the experimenter, or vice versa!

SOCIAL DESIRABILITY BIAS bias occurs when participants respond in a way they perceive as socially acceptable or desirable rather than providing honest responses. In lab experiments, participants may modify their behaviour or responses to avoid judgment or to present themselves in a favourable light. For instance, in a lab study examining attitudes towards recycling, participants might overstate their commitment to recycling if they believe it is socially desirable, even if their behaviour differs.

THE HAWTHORNE EFFECT: This phenomenon refers to changes in behaviour that occur simply because of being observed or participating in an experiment rather than the experimental manipulation itself. When participants are aware of being studied, they may alter their behaviour, consciously or unconsciously, to conform to what they believe is expected by the experimenter. For example, workers in a factory may increase their productivity during a lab study simply because they know they are being observed, regardless of any changes in their working conditions.

INVESTIGATOR EFFECTS refer to the unintentional influence that experimenters or researchers may have on the behaviour or responses of participants in a study. This influence can occur through various means, such as subtle cues, body language, or unintentional biases conveyed by the experimenter during the experiment. For example, suppose an experimenter inadvertently expresses enthusiasm or approval when participants provide certain responses or behaviours. In that case, it may subtly encourage participants to continue or repeat those behaviours, basing the study's results. In a lab experiment investigating the effects of praise on task performance, an investigator effect may occur if the experimenter's tone of voice or facial expressions unintentionally conveys approval or encouragement to participants who receive praise, leading them to perform better on the task. Similarly, if an experimenter shows disinterest or scepticism when participants provide certain responses, it may inadvertently discourage those responses, affecting the overall outcomes of the study.

EXPERIMENTER BIAS

When the researcher’s expectations about the study affect the result, they may indirectly or unconsciously indicate how they want the results.

They may give leading behaviour or questions.

They also may be biased in assessing someone’s behaviour—seeing what they want to see as it supports their hypothesis.

ETHICS: Ethical considerations in lab experiments encompass standard principles such as participant confidentiality, informed consent, and minimizing psychological or physical harm. Unlike field experiments, ethical concerns are typically less pronounced in lab settings since participants are aware of their participation, making obtaining informed consent and managing deception less problematic.

EXAMPLES:

Milgram's Obedience Study: Milgram's experiment occurred in a Yale University laboratory. The controlled environment allowed Milgram to manipulate variables systematically, such as the proximity of the authority figure and the presence of peers, to observe their effects on participant behaviour. The tightly controlled conditions facilitated the replication of the study, enhancing its reliability.

Asch Conformity Experiment: Asch's experiment was conducted in a laboratory environment where participants were seated around a table, with the experimenter and confederates also present. The controlled setting of the lab enabled Asch to manipulate the independent variable (the presence of social pressure) precisely and measure participants' responses to it. This controlled environment allowed for the systematic investigation of conformity under varying conditions.

Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment: Although Zimbardo's study is often called a "field experiment," it occurred in a simulated prison environment within the confines of Stanford University's psychology department. The laboratory-like setting allowed Zimbardo to control various aspects of the experiment, such as selecting and assigning participants to roles, establishing rules and procedures within the simulated prison, and monitoring participant behaviour. While the setting resembled a real-world scenario, the experiment maintained the characteristics of a controlled laboratory study, albeit with ethical concerns regarding participant well-being.