THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

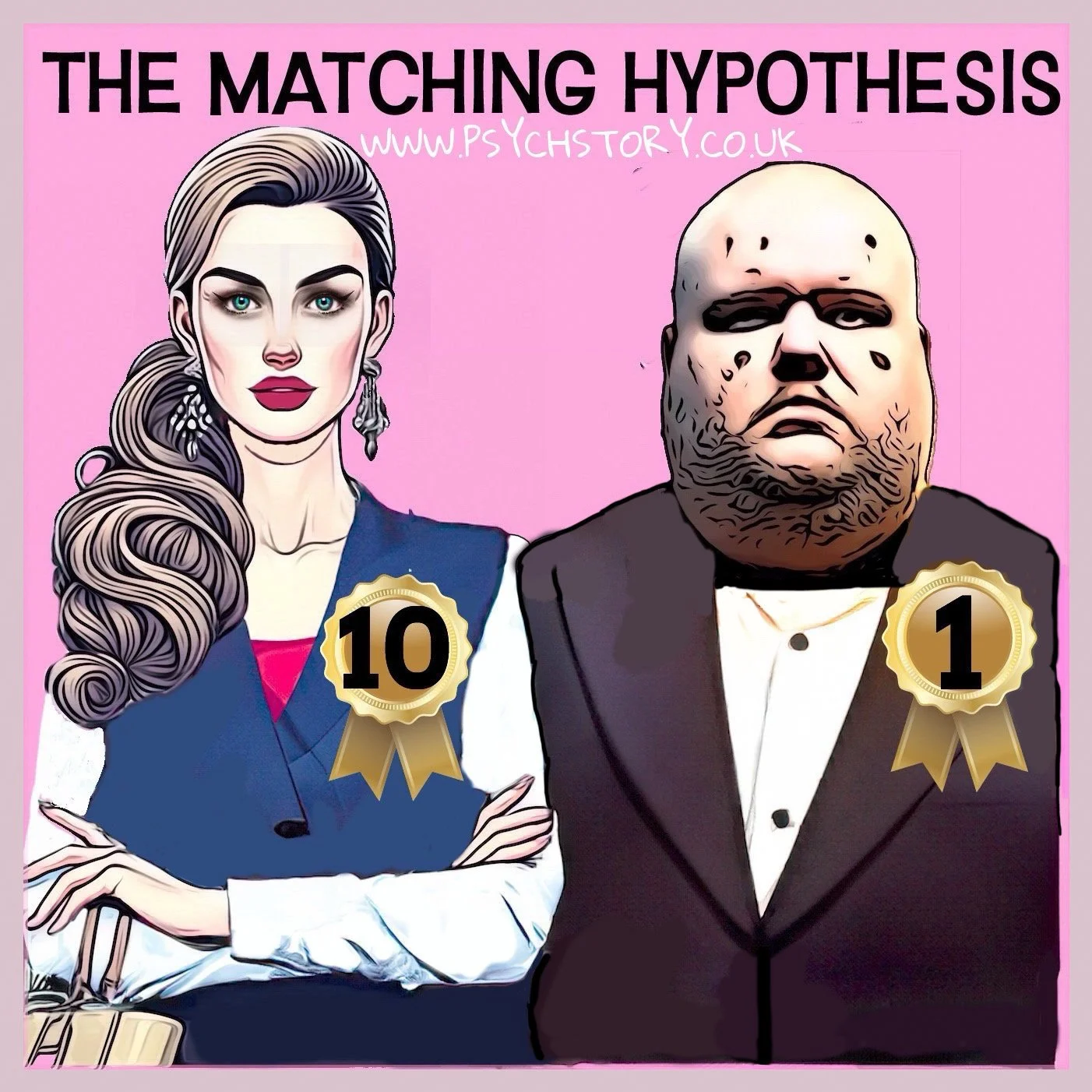

The matching hypothesis, also referred to as the matching phenomenon, suggests that individuals are more likely to enter and maintain committed relationships with partners who are of similar social desirability, particularly in terms of physical attractiveness.

Rather than always aiming for the most attractive person, individuals pursue partners within their attractiveness range, often to reduce the likelihood of rejection and ensure a more stable, reciprocal relationship.

HOW IT WORKS

The core idea is that people make realistic choices when selecting a romantic partner. While initial attraction may lead individuals to seek the most desirable partners, long-term relationships usually balance desirability and attainability. If someone continually aims for a partner who is much more beautiful than they are, they are more likely to experience rejection, leading them to adjust their preferences over time.

In simple terms, if everyone were rated on a scale from one to ten in terms of attractiveness, the theory suggests that:

A person who is a one is more likely to date another person who is a one.

A person who is a five is likelier to date another person who is a five.

A person who is a ten is likelier to date another person who is a ten.

People aim for the most attractive partner but also consider the likelihood of rejection. A person who is a five might be attracted to someone who is a ten, but if they consistently get rejected by people at that level, they will eventually focus on partners within their range. This idea originates from social psychology and was introduced by Elaine Hatfield and colleagues in 1966.

However, while physical appearance plays a central role in attraction, relationships where partners differ significantly in attractiveness may still be successful due to other compensatory factors. For example, individuals with higher social status, wealth, or influence may attract physically attractive partners despite an imbalance in looks. This is often observed in relationships where older, affluent men pair with younger, conventionally attractive women or where physical attractiveness is deprioritised in favour of financial security and social prestige.

RESEARCH STUDIES

WALSTER ET AL. (1966) – THE COMPUTER MATCH DANCE STUDY

Walster et al. (1966) conducted the famous Computer Match Dance study to test the matching hypothesis. They recruited 752 student participants, rated on physical attractiveness by four independent judges, to measure their social desirability. Participants were then told they would be matched with a partner based on a questionnaire assessing similarity. However, the pairings were random (except that no man was paired with a taller woman).

During the dance, participants interacted with their assigned partners, and at an intermission, they were asked to evaluate their date. Findings revealed that physical attractiveness was the primary factor influencing enjoyment of the date, regardless of similarity in personality or intelligence. More physically attractive individuals judged their dates more harshly, and those with higher attractiveness levels reported lower satisfaction with their partners—even when they were similarly attractive. The results suggested that people prefer more handsome partners rather than automatically selecting someone of equal attractiveness, contradicting the matching hypothesis.

However, a follow-up study by Walster et al. found that couples were more likely to continue interacting if they were similarly attractive, offering some support for the hypothesis. One limitation noted by Walster was that the four judges only had brief interactions with participants, and longer exposure could have influenced ratings of attractiveness.

WALSTER AND WALSTER (1971) – FOLLOW-UP STUDY

Walster and Walster (1971) conducted a second study to improve ecological validity. This time, participants were allowed to meet beforehand and interact before deciding on a potential partner. The results differed from the original study, as participants expressed the most liking for partners who were similar in physical attractiveness, supporting the matching hypothesis.

MURSTEIN (1972) – PHOTOGRAPH RATING STUDY

Murstein (1972) provided strong empirical support for the matching hypothesis. He collected photographs of 197 real-life couples at various relationship stages (from casual dating to marriage) and had eight independent judges rate the attractiveness of each individual. The judges were unaware of which people were in a relationship together.

Findings showed that partners tended to be similar in attractiveness, supporting the idea that individuals are more likely to choose partners of comparable physical appeal. Murstein also found that self-perceptions and partner perceptions in the first round of the study were unrealistically high, with individuals rating themselves and their partners more positively. These measures were removed in later rounds to avoid biased results.

HUSTON (1973) – FEAR OF REJECTION

Huston (1973) argued that the matching hypothesis is not based on a preference for similarity but rather on a fear of rejection. In his study, participants were shown photographs of potential partners who had already indicated an interest in them. Participants chose the most attractive partner available, suggesting that people prioritise attractiveness over similarity when rejection is not a risk. However, this study lacked ecological validity, as real-life dating does not provide certainty about a partner’s interest in advance.

WHITE (1980) – REAL-LIFE DATING COUPLES

White (1980) conducted a study on 123 dating couples at UCLA, investigating the relationship between attractiveness and relationship satisfaction. The findings showed that partners with similar attractiveness levels reported higher satisfaction and stronger feelings of love, supporting the matching hypothesis.

The study also suggested that relationships function like a marketplace. If an individual has multiple attractive alternatives, they may devalue their current partner if they believe they can do better. However, if a relationship is strong, individuals may remain loyal, valuing their commitment over potential new options.

GARCIA AND KHERSONSKY (1996) – PERCEPTIONS OF COUPLES

Garcia and Khersonsky (1996) examined how others perceive matching and non-matching couples. Participants viewed photos of couples who were either similar or different in attractiveness and completed a questionnaire rating their satisfaction, likelihood of breakup, and future marital success.

Findings indicated that:

Couples who were both highly attractive were perceived as more satisfied and more likely to have a successful marriage.

In mismatched couples, the less attractive male was rated more satisfied than the more attractive female.

The more attractive female was seen as less satisfied in non-matching couples.

These results suggest that people perceive equal attractiveness as a positive relationship factor.

SHAW TAYLOR ET AL. (2011) – ONLINE DATING STUDY

Shaw Taylor et al. (2011) investigated the matching hypothesis in online dating interactions. The study measured the attractiveness of 60 males and 60 females and tracked their messaging behaviour.

Results showed that people initially reached out to partners who were significantly more attractive than themselves. However, they were more likely to receive a response if they contacted someone closer to their attractiveness level, suggesting that matching occurs as a result of social dynamics rather than conscious preference.

BERSCHEID AND DION (1974) – EXPECTATIONS OF RELATIONSHIP OUTCOMES

Berscheid and Dion (1974) investigated how people perceive the relationships of couples with different levels of physical attractiveness. They hypothesised that individuals would expect relationships between partners of similar attractiveness to have better long-term outcomes than mismatched couples.

METHODOLOGY

Participants were shown photographs of couples who were either well-matched or discrepant (where one partner was significantly more attractive than the other).

They were then asked to rate the couples on several factors, including:

Relationship satisfaction (how happy they seemed)

Marital stability (how likely they were to stay together)

Parental quality (how good they would be as parents)

FINDINGS:

Equally attractive couples were perceived as happier and more likely to have stable, successful relationships.

Mismatched couples (where one partner was more attractive) were seen as less stable, and participants predicted a higher likelihood of breakup.

The study reinforced the matching hypothesis, suggesting that people assume that similarity in attractiveness leads to better relationship outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS:

These findings suggest that societal expectations about relationships favour equity in attractiveness, which may influence dating choices and partner selection. People may unconsciously seek similarly attractive partners due to social norms and a desire for stability.

BERSCHEID AND WALSTER ET AL. (1974) – REPLICATION OF MATCHING EFFECT

Berscheid and Walster et al. (1974) aimed to replicate and expand on previous findings, further investigating how physical attractiveness influences romantic selection.

METHODOLOGY:

Participants were presented with photographs of individuals of varying attractiveness.

They were asked to select a preferred partner for a romantic relationship.

The study also measured how attractiveness influenced expectations of personality traits, relationship satisfaction, and overall desirability.

FINDINGS

Attractiveness was the most influential factor in partner selection. Participants overwhelmingly chose the most physically attractive individuals as their ideal partners.

However, when asked to predict long-term relationship satisfaction, participants expected similarly attractive couples to have more successful relationships.

More attractive individuals were perceived to have better personalities, reinforcing the "halo effect"—the cognitive bias where people assume that physically attractive individuals have more positive traits.

CONCLUSIONS

This study further reinforced the importance of physical attractiveness in romantic selection, supporting both the matching hypothesis and the social desirability bias in relationships. It suggested that:

People are drawn to the most attractive partners but expect similarly attractive couples to have stronger relationships.

Attractiveness influences perceptions of personality, meaning physical appearance affects more than just romantic desirability.

These findings helped cement the role of physical attractiveness in relationship psychology, highlighting its influence on both partner choice and societal expectations of romantic success.

COYE CHESHIRE ET AL. (2011) – ONLINE DATING AND THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

BACKGROUND

Coye Cheshire and his team at UC Berkeley conducted a large-scale study on online dating to test the validity of the matching hypothesis in a modern digital context. Traditionally, the matching hypothesis suggests that individuals select romantic partners based on similar levels of social worth, which has often been equated with physical attractiveness. However, this research explored whether the hypothesis still holds when tested with real-world online dating data.

METHODOLOGY

The study used large-scale online dating data to examine whether people actively select partners of similar attractiveness or aim for more attractive partners. The research was divided into four key experiments:

EXPERIMENT ONE: Investigated whether an individual's feelings of self-worth correlated with the social desirability of the partners they sought.

EXPERIMENT TWO: Examined whether a person’s physical attractiveness correlated with the attractiveness of the people they contacted.

EXPERIMENT THREE: Looked at the popularity of online dating users (measured by unsolicited messages received) and whether it correlated with their perceptions of their partners’ desirability and popularity.

EXPERIMENT FOUR: Assessed whether more popular users chose and were chosen by partners of similar popularity.

FINDINGS

People frequently aimed higher than their level of attractiveness when initiating contact. Users generally reached out to people more attractive than themselves, challenging the idea that individuals instinctively seek partners of equal attractiveness.

Despite this tendency, responses were more likely from partners of similar attractiveness. This suggests that while people may try to date "out of their league," mutual attraction and reciprocation are still influenced by matching in social desirability.

Different measures of social worth led to varying conclusions. While some findings suggested people sought more attractive partners, the study also found that individuals voluntarily selected partners with similar desirability in other areas, such as intelligence or personality.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

The study challenged the traditional view of the matching hypothesis by showing that people often attempt to date more attractive partners rather than instinctively selecting those of similar attractiveness.

However, the findings partially supported the hypothesis, as individuals were ultimately more likely to match with partners of similar desirability once mutual selection was considered.

This research highlights how modern online dating offers a broader selection of potential partners. This may encourage aspirational dating behaviour, where individuals attempt to connect with those they perceive as more attractive.

CONCLUSION

Coye Cheshire’s study demonstrated that while people initially reach out to more attractive partners, they are more likely to form relationships with those of similar social desirability in the long run. This supports a revised version of the matching hypothesis, where individuals may aim higher but match based on mutual interest and compatibility. The study also underscores the complexity of attraction, showing that factors beyond physical attractiveness—such as personality and self-worth—play a significant role in partner selection.

SUMMARY OF RESEARCH FINDINGS

Early studies (Walster et al., 1966) challenged the matching hypothesis, showing that people prefer the most attractive partner possible.

Later studies (Walster & Walster, 1971; Murstein, 1972; White, 1980) supported the hypothesis, demonstrating that real-life couples tend to be similarly attractive.

Alternative explanations (Huston, 1973; Brown, 1986) suggest that fear of rejection or learned expectations contribute to matching rather than deliberate selection.

Recent studies (Shaw Taylor et al., 2011) indicate that people aim high but match based on realistic social interactions.

These findings highlight the complexity of attraction, with social, psychological, and evolutionary factors all playing a role in relationship formation.

EVALUATION OF THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

LIMITATIONS OF PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS AS THE MAIN FACTOR

One of the main criticisms of the Matching Hypothesis is that it places too much emphasis on physical attractiveness as the foundation for relationship formation. In reality, relationships are influenced by multiple factors, including personality, intelligence, shared values, and social background. While physical attractiveness may play a role in initial attraction, long-term compatibility often depends on other qualities.

There are many examples of relationships where partners do not appear to be evenly matched in attractiveness. It is common to see one partner significantly more attractive than the other, suggesting that factors such as wealth, social status, humour, or emotional connection can compensate for differences in physical appeal. Some argue that the Matching Hypothesis oversimplifies relationship dynamics by assuming that attractiveness is the main criterion for partner selection.

POWER IMBALANCES IN RELATIONSHIPS

However, the original Matching Hypothesis does not claim that partners have equal agency in choosing a mate, as social and economic power dynamics often influence real-world relationships. For example, a less attractive partner may compensate with other resources, such as financial stability or social connections. This suggests that, although criticism of this theory is common, it is not entirely valid.

Indeed, the Matching Hypothesis suggests that relationships are formed based on a cost-benefit analysis, where individuals weigh the rewards and drawbacks of a potential partner. In this context, women may be more likely to choose less physically attractive men if those men offer higher social status, financial security, or resources that contribute to long-term stability. This aligns with evolutionary theory, which argues that men and women have different reproductive strategies. Since women have a higher biological investment in offspring, they are more likely to prioritise resource acquisition over physical attractiveness when selecting a partner.

Thus, when compensation for looks occurs, women are more likely to trade physical attractiveness for wealth and status than men. This suggests two key points:

If a couple has the same social status, attractiveness tends to be more evenly matched, as no bargaining power is involved. In such cases, partners of equal economic and social standing may only be able to trade looks rather than other attributes.

The Matching Hypothesis is beta-biased, assuming that relationship formation works similarly for both sexes without fully considering gender-specific preferences. However, in reality, the Matching Hypothesis is alpha-biased, as evidence suggests that women are more likely than men to accept less attractive partners if they are from higher income or social classes.

This highlights an essential difference between the sexes that the theory does not fully account for. Again, evolutionary theory suggests that these patterns may be more relevant to men, as they have historically competed for high-status positions to attract mates. This reinforces the idea that attractiveness and status function differently for each gender in mate selection.

BROWN (1986) – LEARNED EXPECTATIONS AND THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

KEY ARGUMENT

Brown (1986) supported the matching hypothesis but provided an alternative explanation for why individuals form relationships with partners of similar attractiveness. Rather than choosing partners based on a fear of rejection, he argued that people develop a learned sense of what is "fitting" for them in relationships.

Individuals adjust their expectations based on what they can offer in a relationship. This self-assessment is shaped over time by social experiences, interactions, and feedback from others. Instead of aiming for the most attractive partner possible and fearing rejection, people naturally select partners they believe are realistic choices based on their perceived attractiveness and desirability.

Brown suggested that people internalise social feedback about their attractiveness, influencing their perception of their romantic value. Those who receive consistent validation of their attractiveness tend to have higher expectations for partners. Conversely, individuals who receive less positive social reinforcement may adjust their expectations downward and seek partners they believe they can realistically attract.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

Brown’s theory shifts the explanation away from a simple fear of rejection and towards self-perception and social learning. This explanation aligns with social exchange theory, as individuals subconsciously evaluate their value and seek equitable relationships where they feel desirable and secure. It also accounts for individual differences, as some people may overestimate or underestimate their attractiveness based on subjective self-perception rather than objective reality.

However, self-perception alone does not fully explain why some relationships are unequal, particularly those between wealthy men and beautiful women. According to Brown, these men are likely aware of the imbalance in attractiveness between themselves and their partners. Still, they may not fear rejection because their financial resources compensate for their lower physical appeal. This suggests that self-perception is only relevant when rejection is a concern—if an individual has other desirable attributes, they may feel secure despite an attractiveness disparity.

An imbalance in attractiveness may lead to feelings of inadequacy for men or women who lack alternative bargaining power. They might fear their partner will eventually leave them for someone of equal attractiveness, reinforcing that relationship stability depends on perceived equity.

Despite this, most people still desire the most attractive partner possible. However, self-perception, a lack of bargaining power, and fear of rejection prevent most individuals from actively pursuing the most beautiful people. Instead, people settle for more realistically attainable partners, making strategic choices based on what they can offer in return.

This is reflected in celebrity culture and parasocial relationships. The most admired public figures are rarely average-looking, as people consistently idolise the most conventionally attractive stars. The billions spent on plastic surgery and the beauty industry further illustrate that while people aspire to the most physically desirable partners, they ultimately negotiate based on what they can realistically achieve, whether through their looks, status, or other compensatory factors.

For this reason, the matching hypothesis shares key similarities with social exchange theory, as both suggest that relationships involve an assessment of personal value and strategic partner selection.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL INFLUENCES

The Matching Hypothesis assumes that attraction operates universally, but cultural and societal norms significantly shape relationship choices. In some cultures, family influence, arranged marriages and economic considerations may take precedence over physical attractiveness, leading to partner selection based on factors beyond romantic attraction alone.

Additionally, one common criticism of the theory is that standards of attractiveness vary across cultures and historical periods, making the concept of matching seem subjective and fluid rather than a fixed rule. However, this criticism misinterprets the hypothesis. The Matching Hypothesis does not dictate what is considered attractive; rather, it states that individuals match with others based on the prevailing standards of attractiveness within their culture and social context.

Regardless of cultural differences in beauty ideals, many societies prioritise what they consider attractive as a bargaining tool in mate selection. Even in cultures where wealth, status, or family expectations dominate partner choice, physical attractiveness remains an important factor within the parameters of those cultural norms. This suggests that while the specific traits deemed attractive may vary, the tendency to use attractiveness as a social currency in mate selection is a consistent pattern across cultures.

This reinforces the idea that, rather than being invalidated by cultural differences, the Matching Hypothesis can be adapted to different social contexts, as it primarily describes a pattern of relationship formation rather than prescribing a fixed standard of beauty.

THE ROLE OF INDIVIDUAL PREFERENCES

Not everyone values attractiveness to the same extent. Some people prioritise emotional compatibility, intelligence, or shared interests overlooks. The hypothesis assumes people will naturally settle for someone at their attractiveness level, but individual preferences can lead to pairings that do not fit the expected pattern.

CHALLENGES FROM ONLINE DATING

The rise of online dating and social media presents significant challenges to the Matching Hypothesis, as it disrupts traditional mechanisms of partner selection. The hypothesis suggests that people choose partners based on realistic expectations of attainability, but modern dating platforms encourage idealised choices over practical ones.

IDEALISED ATTRACTION AND CURATED IDENTITIES

Dating apps and social media enable users to present highly curated versions of themselves, often through edited photos, carefully crafted profiles, and selective self-disclosure. This can distort perceived attractiveness, making individuals more likely to pursue partners outside their realistic attractiveness range. Rather than basing choices on real-world interactions, where rejection acts as a natural filter, online dating removes immediate feedback, allowing people to aim for more attractive partners than they might in face-to-face settings.

EXPANDED SOCIAL POOLS AND BROKEN BARRIERS

Traditional relationship formation was primarily restricted to immediate social circles, such as workplaces, universities, and community networks, where individuals were more likely to encounter people of similar social desirability. Online dating removes these geographic and social constraints, allowing people to connect with partners far beyond their usual environment. This increases opportunities for asymmetrical pairings, where partners may not align in attractiveness, status, or background.

DECOUPLING PHYSICAL APPEARANCE FROM RELATIONSHIP SUCCESS

While physical attractiveness still plays a role in initial attraction, online dating emphasises other factors, such as personality descriptions, shared interests, and communication skills. Long-distance relationships, which are far more common due to online interactions, often begin with text-based exchanges rather than visual attraction alone. This means that people may form emotional bonds before meeting in person, potentially leading to relationships where traditional matching based on looks is less relevant.

INCREASED REJECTION AND UNREALISTIC EXPECTATIONS

Despite the illusion of choice and limitless options, research suggests that online dating increases rejection rates as people compete for the most attractive users. This creates a paradox where individuals pursue partners well above their attractiveness level, only to experience frequent rejection, reinforcing self-perception biases. At the same time, the accessibility of lovely individuals online may discourage people from settling for realistic matches, leading to prolonged singleness or dissatisfaction with attainable partners.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

While online dating does not invalidate the Matching Hypothesis entirely, it introduces new variables that complicate its traditional application. People may still seek partners within their attractiveness range, but expanded options, curated identities, and delayed face-to-face interaction allow more flexibility in mate selection. This suggests that while the Matching Hypothesis remains relevant, modern dating requires a more nuanced approach, incorporating social and technological influences into relationship formation.

LACK OF CONSISTENT EVIDENCE

While some studies support the Matching Hypothesis, research findings have been inconsistent, raising questions about its reliability. One major issue is that much of the data supporting the theory is correlational and non-experimental, making it difficult to establish cause and effect. Just because partners often appear to be matched in attractiveness does not mean that this is the reason they formed a relationship—other factors, such as shared social circles, mutual interests, or cultural norms, could influence partner selection. Without experimental manipulation, it is impossible to determine whether people actively seek partners of similar attractiveness or whether other forces naturally lead to such pairings.

Another common misconception about the Matching Hypothesis is that it only applies to physical attractiveness. However, the original theory does not state that looking alone determines romantic pairings. Instead, it suggests that people match based on overall social desirability, including personality, intelligence, wealth, status, or shared values. Studies that claim to contradict the hypothesis by showing that people pair based on other traits rather than looks may be misrepresenting the theory rather than disproving it. This misconstrual leads to confusion, as some researchers attempt to falsify the hypothesis based on an oversimplified, appearance-based interpretation rather than testing it in its intended, broader form.

Furthermore, findings on mate selection vary depending on context. Some studies suggest that attractiveness is more dominant in short-term dating scenarios. At the same time, factors such as personality, emotional compatibility, and financial stability become more influential in long-term relationships. This suggests that matching may operate differently across relationship types, further complicating efforts to test the hypothesis consistently.

Ultimately, the lack of experimental control, variability in findings, and frequent misinterpretation of the theory make it challenging to assess the actual validity of the Matching Hypothesis, leaving room for debate on its applicability in different relationship contexts.

THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS AND SAME-SEX RELATIONSHIPS

The Matching Hypothesis is often applied to heterosexual relationships, but its relevance to same-sex relationships is less frequently explored. While the theory should, in principle, apply to all romantic partnerships, research suggests that gay and lesbian individuals may prioritise different factors in mate selection, which complicates how matching occurs in non-heterosexual relationships.

Gay men tend to place greater emphasis on physical attractiveness, similar to heterosexual men. Studies suggest that appearance-based matching is more prevalent in gay male dating culture, particularly in casual relationships. Physical traits such as youth, body shape, and facial symmetry often play a key role in attraction. This is reflected in online dating patterns, where gay men frequently assess potential partners based on looks before considering other factors. While long-term relationships involve more than just physical appeal, initial matching based on attractiveness appears stronger among gay men than lesbians.

In contrast, lesbians are generally less focused on physical attractiveness than both gay and straight men. Research suggests that emotional compatibility, personality, and shared life goals are more influential in lesbian relationships. This aligns with evidence that lesbian couples tend to engage in fewer short-term or casual relationships and prioritise long-term commitment more often. As a result, the matching process in lesbian dating may be based more on emotional bonding and shared interests rather than social desirability alone.

These differences challenge the Matching Hypothesis, as it assumes a universal focus on attractiveness, yet the importance of looks varies significantly depending on gender and sexual orientation. The theory appears to be more applicable to gay men, who tend to match on physical attractiveness, but less so for lesbians, who may prioritise other attributes. This also raises questions about how socialisation and gender roles influence mate selection, as men—regardless of sexual orientation—are generally more likely to emphasise physical traits. In contrast, women are often socialised to value emotional depth and long-term stability.

Additionally, the Matching Hypothesis assumes that attractiveness remains a stable factor in relationships, yet in both heterosexual and same-sex relationships, desirability can shift over time. A couple may start as an equal match in attractiveness or status, but changes such as ageing, weight gain, financial success, or career shifts can create disparities over time. Someone initially seen as desirable due to wealth may lose financial stability, or a once physically attractive partner may experience health-related changes. This suggests that while matching may explain initial attraction, it does not necessarily predict long-term compatibility.

Finally, the theory does not fully consider how relationships form in different social contexts. In same-sex dating, proximity, community size, and partner availability can shape mate selection in ways that differ from heterosexual dating. For example, in smaller LGBTQ+ communities, individuals may have fewer options to choose from, making matching based on attractiveness or social status less relevant than shared values and mutual understanding.

Ultimately, while the matching hypothesis can be applied to same-sex relationships, modifications are required to account for differences in mate selection priorities. In particular, the theory should be expanded beyond just attractiveness to reflect the role of emotional connection, long-term compatibility, and changing desirability over time.

THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS AND RELATIONSHIP PRIORITIES

A key limitation of the Matching Hypothesis is that partner selection priorities change depending on whether an individual seeks a short-term or long-term relationship. While physical attractiveness is often central to initial attraction, it is not always the most critical factor in sustaining a long-term relationship.

Individuals tend to prioritise attractiveness for short-term dating, as these relationships are often based on immediate appeal rather than deeper compatibility. This aligns with the Matching Hypothesis, as people usually seek the most physically desirable partner they can attract. However, other traits such as kindness, emotional stability, and shared values become more important in long-term relationships. Research suggests that similarity in personality and life goals plays a more significant role in relationship satisfaction.

Some individuals also have different priorities for different types of relationships. They may seek an attractive partner for casual dating but prioritise emotional depth and reliability in a long-term partner. This suggests that matching is not solely based on attractiveness but on shifting priorities.

Furthermore, kindness, emotional intelligence, and compatibility influence relationship longevity. While the Matching Hypothesis explains initial attraction, it does not fully account for why some physically mismatched couples stay together while others who initially appeared well-matched eventually separate.

This suggests that while the Matching Hypothesis provides insight into early attraction, it overlooks the changing nature of mate selection and the role of personal attributes in long-term relationship success.