THE HALO EFFECT

SPECIFICATION: Factors affecting attraction in romantic relationships: physical attractiveness and the matching hypothesis – the impact of physical appearance on attraction and the tendency for individuals to seek partners with a similar level of attractiveness.

INTRODUCTION

Humans are an undeniably vain species. Whether we admit it or not, much of our daily effort revolves around appearance, social desirability, and the pursuit of attraction. We like to believe that self-care is a deeply personal endeavour. We have never even seen our real face in the flesh, and we never will! We only know what we look like in 2D because mirrors and selfies do not tell us the truth. Strangely, almost everyone we meet knows our faces better than we do. Despite this "face blindness," we are unspeakably vain.

Our investment in beauty, fitness, and self-presentation is rarely just for ourselves. Instead, it is often driven by how we wish to be perceived by others because we recognise that our appearance is highly marketable in attracting romantic partners.

SOME STATISTICS ON OUR VANITY:

People spend 1–2 hours grooming, showering, dressing, and personal care daily. Over a lifetime, this adds up to several years spent on appearance.

The global cosmetic industry exceeded £400 billion as of 2023.

15.1 million people had cosmetic procedures worldwide 2020, showing that many actively alter their looks to enhance attractiveness.

Over 40% of adults in the UK and US attempted to lose weight through dieting in 2020, often for aesthetic reasons.

Billions of selfies are uploaded daily, with many being digitally altered or filtered to enhance attractiveness before being shared online.

£8 billion was spent on beauty product advertising in 2019, reinforcing how much effort people put into looking attractive.

DO WE DRESS FOR OURSELVES OR OTHERS? LOCKDOWN REVEALED THE TRUTH

If attraction were indeed about self-satisfaction, people would not spend so much time and money improving their looks for the outside world. Our obsession with filters, plastic surgery, and fashion all indicate that appearance plays a significant role in romantic attraction.A considerable test of whether we present ourselves for others or ourselves happened during the Covid-19 lockdowns. With no social engagements, office environments, or public appearances, our collective effort toward attractiveness collapsed overnight.

Sales of makeup, perfume, and high heels plummeted while sales of tracksuits and pyjamas surged.

People stopped styling their hair, shaving, or wearing makeup because there was no external audience.

The rise of "Zoom dressing" showed how people prioritised looking good only for what was visible on a screen while wearing tracksuit bottoms and slippers outside the camera’s view.

This shift was not a rejection of attractiveness but proof that we only invest in appearance when there is someone to impress. The moment social settings disappeared, so did the motivation to dress up or groom excessively. This demonstrates that attractiveness is socially driven rather than purely personal.

CONCLUSION

However, what exactly determines who we find attractive and why? Psychological and evolutionary theories have sought to explain the patterns behind romantic attraction, revealing that our choices are not as spontaneous as we might think.

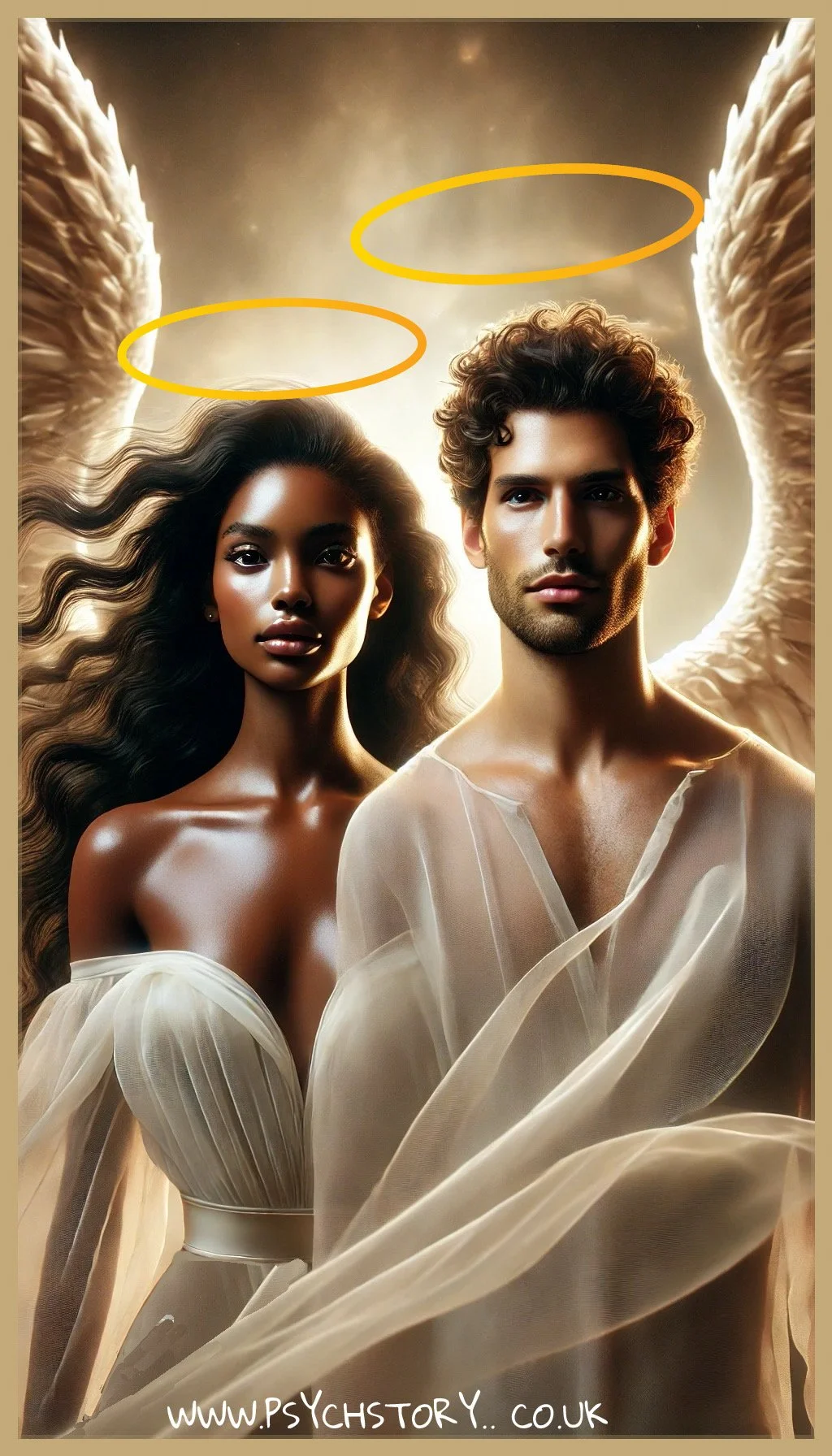

The halo effect demonstrates how attractiveness distorts perceptions, leading people to assume that physically appealing individuals also possess desirable personality traits.

Sexual selection theory explores how evolutionary pressures have shaped mate preferences, favouring traits that signal reproductive fitness and social advantage.

Finally, the matching hypothesis suggests that people are driven by their ideal preferences and a pragmatic understanding of their attractiveness, leading them to pursue partners of similar social desirability.

These theories provide a scientific framework for understanding attraction, offering insight into the hidden mechanisms that shape romantic relationships. Whether driven by perception biases, evolutionary instincts, or social negotiation, attraction is far from random—it follows predictable patterns that can be examined, tested, and understood. Let’s explore them in more detail now.

THE HALO EFFECT

DEFINITION AND ORIGIN

The halo effect called the halo error, is a cognitive bias where an individual's overall impression of a person, company, product, or brand in one area influences their perception of unrelated traits. Depending on the initial impression, this can lead to an overly optimistic or negative assessment. The term was first introduced by Edward Thorndike in his 1920 study "A Constant Error in Psychological Ratings," in which he observed that military officers tended to rate their subordinates positively across multiple unrelated traits simply because they had a favourable perception of one characteristic, such as physical appearance or intelligence.

This bias can cause distorted judgment in various contexts, including personal relationships, business, marketing, education, and the legal system. A classic example of the halo effect occurs when someone perceives a physically attractive person as more intelligent, competent, and trustworthy, even without any evidence for these qualities.

HOW THE HALO EFFECT WORKS

The halo effect operates through a mental shortcut where people fill in missing information about an individual or entity based on a single known trait. This simplifies decision-making but often leads to errors in judgment. It is an unconscious bias where one positive characteristic, such as attractiveness or charisma, shapes a person's perception of various unrelated traits.

FOR EXAMPLE:

If someone sees a well-dressed, physically attractive individual, they may assume that the person is intelligent, kind, and successful.

Conversely, if someone looks dishevelled or unkempt, they might be perceived as lazy or untrustworthy, even if there is no basis for such assumptions.

This mental shortcut reflects an individual’s preferences, prejudices, ideology, and social perception, making the halo effect a powerful yet often inaccurate tool in human judgment.

THE HORN EFFECT – THE OPPOSITE OF THE HALO EFFECT

The horn effect is the negative counterpart to the halo effect. While the halo effect causes individuals to overestimate someone's positive traits, the horn effect leads people to assume negative qualities based on a single undesirable characteristic.

FOR EXAMPLE:

People with messy hair and poor posture may be perceived as lazy or incompetent, even if they are highly skilled.

If a company releases a single flawed product, consumers may lose trust in the entire brand, even if their other products are high quality.

Both the halo and horn effects demonstrate how cognitive biases shape our perceptions, leading us to make snap judgments rather than evaluating situations objectively.

APPLICATIONS AND CONTEXTS

PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIAL PERCEPTION

In psychology, the halo effect is considered a perception distortion, meaning that people interpret new information about someone through the lens of their initial impression. This can lead to confirmation bias, where individuals actively seek evidence supporting their pre-existing beliefs while ignoring contradictory information.

For example, suppose someone initially perceives a politician as charismatic and competent. In that case, they may be less likely to believe accusations of corruption against them, dismissing such claims as exaggerations or misunderstandings.

Similarly, in interpersonal relationships, if a person has a positive first impression of someone, they may overlook negative traits such as dishonesty or arrogance.

THE HALO EFFECT IN EDUCATION

Teachers and educators are not immune to the halo effect. Research suggests that teachers may rate more attractive students as more intelligent or capable, even when there is no difference in academic performance. This can lead to grade inflation or biased assessments, where physically attractive students receive higher marks or more favourable evaluations.

For example:

A teacher may assume that a well-groomed and confident student is more intelligent and hardworking, leading them to overlook mistakes or give them the benefit of the doubt in grading.

Conversely, a dishevelled or socially awkward student may be perceived as less competent, even if their academic performance is strong.

THE HALO EFFECT IN MARKETING AND ADVERTISING

The halo effect is widely used in marketing and branding, where companies create positive associations between their products and attractive individuals, celebrities, or desirable qualities.

For example:

Apple’s sleek design and branding create a halo effect, leading consumers to perceive Apple products as superior in functionality, even if competitors offer similar or better technology.

Celebrity endorsements rely on the halo effect, as consumers assume that if a popular or attractive celebrity uses a product, it must be high quality.

This bias influences consumer decisions, making people more likely to purchase, trust, and remain loyal to brands they associate with positive traits.

THE HALO EFFECT IN THE WORKPLACE

The halo effect is prevalent in hiring and promotions. Employers may unconsciously favour job candidates who are well-dressed, confident, or attractive, assuming that they are also more competent, reliable, and skilled.

For example:

A good-looking and confident applicant may receive better job offers, even if their qualifications are equal to or less than another candidate's.

Employees who make a strong first impression are often promoted more quickly, as they are seen as more capable than their peers.

This can lead to inequality in hiring practices, with less attractive but highly competent individuals being overlooked.

THE HALO EFFECT IN THE LEGAL SYSTEM

Studies have shown that the halo effect can impact legal judgments and jury decisions.

For example:

Attractive defendants are more likely to receive lighter sentences as they are perceived as less dangerous or more trustworthy.

Physically attractive victims may receive more sympathy, leading to harsher punishments for their attackers.

Unattractive individuals, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, are often judged more harshly in court, reinforcing social biases.

This highlights how the halo effect can contribute to unfair legal outcomes, with appearance influencing perceptions of guilt and innocence.

SUPPORTING RESEARCH

DION, BERSCHEID, AND WALSTER (1972) – ORIGINAL STUDY ON THE HALO EFFECT

AIM

To investigate whether physical attractiveness influences perceptions of personality traits and social competence.

PROCEDURE

Participants were shown photographs of three individuals (strangers) and asked to rate them across various categories, including personality traits such as happiness, career success, and intelligence.

The ratings were compared to an attractiveness rating assigned to each photograph based on evaluations from 100 students.

FINDINGS

Individuals rated as more physically attractive were also perceived as possessing more positive traits, including higher intelligence, greater social competence, and increased overall happiness.

The less attractive individuals were rated lower on these positive characteristics despite no factual basis for this judgement.

CONCLUSION

The study provided strong evidence for the halo effect, demonstrating that people unconsciously attribute positive personality traits to individuals based solely on their physical appearance.

This cognitive bias suggests that attractiveness can influence social perception, potentially affecting job recruitment, legal judgments, and romantic attraction.

LANDY AND ARONSON (1969) – THE HALO EFFECT IN A LEGAL CONTEXT

Landy and Aronson found that attractiveness affects legal outcomes, particularly in criminal trials. Their study showed that more attractive victims led to harsher punishments for defendants, whereas attractive defendants were treated more leniently by mock jurors. This suggests that the halo effect extends beyond social and romantic contexts, influencing legal judgments and moral perceptions.

FEINGOLD (1988) – META-ANALYSIS OF THE HALO EFFECT IN RELATIONSHIPS

Feingold conducted a meta-analysis of 17 studies examining the link between attractiveness and perceived personality traits in real-life relationships. He found that the halo effect persisted across various settings, reinforcing that physical appearance significantly influences how people are evaluated in personal and professional interactions.

CRITICISMS AND LIMITATIONS OF THE HALO EFFECT

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

The traits perceived as attractive and desirable vary across cultures.

For example, in Western cultures, tanned skin is often seen as attractive, whereas in some Asian cultures, pale skin is preferred.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

Not everyone is equally susceptible to the halo effect. Some individuals make more objective assessments, especially when trained to focus on specific criteria, such as hiring managers trained in unbiased recruitment.

SITUATIONAL FACTORS

The halo effect is not absolute and can be overridden by substantial evidence.

For instance, if a beautiful individual is repeatedly caught cheating or lying, their positive image may eventually be reversed.

CONCLUSION

The halo effect is a widespread cognitive bias that influences judgments in personal relationships, education, business, marketing, and the legal system. While it can sometimes lead to beneficial assumptions, it also reinforces social inequality, allowing specific individuals to gain unjust advantages while disadvantaging others.

Understanding the halo effect is crucial for making more objective evaluations and reducing bias in decision-making. By being aware of this tendency, individuals and organisations can take steps to challenge assumptions, focus on factual evidence, and create fairer, more balanced assessments of people, products, and situations.

PHYSICAL ATTRACTION AS AN INDICATOR OF GENETIC FITNESS

THE ROLE OF SEXUAL SELECTION IN PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS

Sexual selection explains why humans have evolved preferences for specific physical traits that signal genetic fitness, health, and reproductive viability. If a trait makes an individual more attractive to the opposite sex, it increases their chances of securing a mate and passing on their genes. Over generations, these traits become exaggerated and widespread.

While other factors such as wealth, status, and dominance can influence mate choice, this discussion focuses purely on physical appearance—what we look like and why certain features are attractive.

NATURAL SELECTION VS. SEXUAL SELECTION

Natural selection ensures survival by favouring traits that help individuals stay alive and reproduce.

Sexual selection focuses on attraction, favouring traits that make an individual more desirable to potential mates, even if they do not directly aid survival.

PLEASE NOTE: While other factors such as wealth, status, and dominance can influence mate choice, this discussion focuses purely on physical appearance—what we look like and why certain features are attractive. For a discussion on non-physical traits such as power and resources, see the topic on sexual selection.

PHYSICAL TRAITS PREFERRED IN WOMEN

FACIAL SYMMETRY

Research suggests symmetrical faces are more attractive because symmetry indicates developmental stability. If a person develops symmetrically, it suggests they have not been significantly affected by genetic mutations, disease, or environmental stressors during growth. Asymmetry, on the other hand, can indicate poor health or genetic defects.

HIP-TO-WAIST RATIO (0.7, HOURGLASS FIGURE)

A waist-to-hip ratio of 0.7 is widely recognised as an indicator of fertility and good health. This proportion is linked to higher fertility due to optimal oestrogen levels, a lower risk of diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions, and an evolutionary advantage in childbirth, as broader hips facilitate labour.

This preference may also function as a natural deterrent against prepubescent females, ensuring men direct reproductive efforts towards women of childbearing age.

YOUTHFUL FEATURES

Signs of youth indicate higher reproductive potential, making them desirable. These include:

clear skin, free from blemishes, wrinkles, or visible signs of ageing, suggesting good health and high oestrogen levels

long, thick hair, associated with youth and fertility, as hair naturally thins with age

bright, white teeth, indicating good health, strong genetics, and proper nutrition

NEONATAL FACIAL FEATURES

Women with big eyes, a small nose, and full lips are often perceived as more attractive because these features are linked to high oestrogen levels and fertility. They also create a more youthful appearance, reinforcing their desirability.

LARGE BREASTS AND FULL BUTTOCKS

Larger breasts and rounded buttocks are often considered attractive because they signal reproductive health and fertility. These features are linked to higher fat stores, which are necessary for pregnancy and lactation, and DHA storage, an essential fatty acid crucial for foetal brain development.

PHYSICAL TRAITS PREFERRED IN MEN

FACIAL SYMMETRY

Just as in women, symmetrical male faces are preferred because they signal genetic stability and resistance to disease.

HEIGHT

A taller stature is generally more attractive in men, potentially because it suggests physical strength and protection, reflects good genetic health and developmental stability and aligns with sexual dimorphism, where males are larger than females in many species.

BROAD SHOULDERS AND V-SHAPED TORSO

Men with broad shoulders and a narrow waist (inverted triangle shape) are often seen as more attractive because this body structure is linked to high testosterone levels, physical strength, and the ability to compete successfully for resources.

STRONG JAWLINE AND PROMINENT BROW RIDGE

Testosterone influences the development of strong facial features, such as a defined jawline and pronounced brow ridge. These traits are associated with high testosterone levels, strong immune function, and good genetics, contributing to masculine attractiveness.

LOW BODY FAT AND MUSCLE DEFINITION

A lean, muscular build is considered attractive as it signals good physical health, lower risk of metabolic diseases, high testosterone levels linked to muscle growth and strength, and the ability to compete successfully in physical confrontations.

PENIS SIZE

Some research suggests that penis size may play a role in physical attraction. A larger size may enhance perceived masculinity, though it is unlikely to have played a significant role in evolutionary fitness beyond a visual cue of virility.

PHYSICAL TRAITS BOTH SEXES FIND ATTRACTIVE

Certain physical traits are universally appealing, indicating genetic health and overall fitness. These include:

Symmetrical body and face, which signal stable development and strong genetics

Clear, smooth skin, which suggests youth, strong immunity, and high reproductive potential

Healthy teeth, which reflect good nutrition and strong genetics

Shiny, well-maintained hair, which is a sign of overall vitality

As studies suggest, genetic dissimilarity results from our being drawn to partners with different immune system genes, which enhances offspring survival. This is detected through scent, particularly during sexual arousal.

WHY PHYSICAL ATTRACTION MATTERS

Physical attraction is not just about aesthetics—it is an evolutionary mechanism that helps individuals identify healthy, fertile, and genetically fit mates.

While modern social factors like status and wealth influence attraction, biological instincts still drive a preference for physical traits that historically increased reproductive success. These preferences, shaped over thousands of generations, continue to influence how we perceive beauty today.

RESEARCH STUDIES

Here are key research studies that support the role of physical attractiveness in sexual selection theory:

FACIAL SYMMETRY AND ATTRACTIVENESS

Little, A. C., Jones, B. C., & DeBruine, L. M. (2011) – This study found that facial symmetry is consistently rated as more attractive across cultures. Symmetry is believed to signal developmental stability, meaning fewer genetic mutations or environmental stressors impacted growth.

Thornhill, R., & Gangestad, S. W. (1999) – Their research on facial symmetry showed that women prefer more symmetrical male faces, particularly at peak fertility in their menstrual cycle. This supports the idea that symmetrical features indicate genetic fitness and enhance reproductive success.

HIP-TO-WAIST RATIO AND FEMALE ATTRACTIVENESS

Singh, D. (1993, 2002) – Singh's studies confirmed that a waist-to-hip ratio of 0.7 is consistently perceived as more attractive in women across different cultures. This preference is linked to fertility and health, reflecting optimal oestrogen levels and lower risks of obesity-related diseases.

Zaadstra et al. (1993) – Found that women with a lower waist-to-hip ratio have higher fertility and a greater likelihood of conception, supporting the evolutionary basis for this preference.

HEIGHT AND MALE ATTRACTIVENESS

Pawlowski, B., Dunbar, R. I. M., & Lipowicz, A. (2000) – Found that women overwhelmingly preferred taller men as romantic partners. The study suggested that height correlates with social status and perceived genetic fitness, making it a desirable trait in mate selection.

Stulp, G., Buunk, A. P., Pollet, T. V., Nettle, D., & Verhulst, S. (2013) – Examined over 10,000 couples and found that taller men had higher reproductive success, reinforcing the evolutionary importance of height in male attractiveness.

STRONG JAWLINES, MASCULINE FEATURES, AND TESTOSTERONE

Johnston, V. S., Hagel, R., Franklin, M., Fink, B., & Grammer, K. (2001) – Found that men with strong jawlines and prominent brow ridges were rated more attractive. These features are linked to higher testosterone levels, which may indicate genetic strength and immune system competence.

Penton-Voak, I. S., & Perrett, D. I. (2000) – showed that women prefer more masculine faces when ovulating but shift towards less masculine faces at other times, suggesting that testosterone-linked features signal short-term genetic benefits rather than long-term parental investment.

NEONATAL FEATURES IN FEMALE ATTRACTIVENESS

Perrett, D. I., Lee, K. J., Penton-Voak, I., Rowland, D., & Yoshikawa, S. (1998) – Found that big eyes, full lips, and small noses were universally rated more attractive in women. These features signal high oestrogen levels and fertility.

MUSCULARITY AND MALE ATTRACTIVENESS

Frederick, D. A., & Haselton, M. G. (2007) – Found that women rated muscular men as more attractive for short-term relationships, suggesting that muscle mass signals good genes and physical dominance, advantageous in ancestral environments.

PENIS SIZE AND PERCEIVED ATTRACTIVENESS

Dixson, B. J., Grimshaw, G. M., Linklater, W. L., & Dixson, A. F. (2013) – Found that larger penis size was associated with increased attractiveness, particularly when paired with taller height and broad shoulders, supporting the idea that secondary sexual characteristics contribute to mate selection.

UNIVERSAL ATTRACTIVENESS OF SYMMETRY AND CLEAR SKIN

Grammer, K., Fink, B., Møller, A. P., & Thornhill, R. (2003) – Found that clear skin, facial symmetry, and healthy hair are universally preferred traits because they indicate good health and genetic quality.

FEMALES SPEND TIME ON THEIR APPEARANCE TO ATTRACT A MALE

Research on intra-sexual selection, particularly regarding females investing time in their appearance to attract a mate, provides valuable insights into mating strategies and behaviours. Several studies have explored this phenomenon:

Feingold (1990) conducted a meta-analysis examining gender differences in physical attractiveness. The study found that women generally place a higher emphasis on their physical appearance compared to men. This suggests that females invest time and effort in enhancing their attractiveness to attract potential mates.

Buss (1989) carried out a cross-cultural study on mate preferences, finding that physical attractiveness was consistently rated as a highly desirable trait in potential mates across different cultures. This suggests that women may invest time in their appearance to increase their attractiveness and reproductive success.

Cash et al. (1985) researched body image and self-esteem, focusing on how individuals perceive their physical appearance. The study found that women often engage in grooming and cosmetic practices to enhance their physical attractiveness, which may be driven by intrasexual competition and the desire to attract potential mates.

Townsend and Wasserman (2011) investigated mate selection strategies in a speed-dating setting. The study found that women tended to spend more time grooming and dressing up before the speed-dating event than men. This suggests that females may prioritise their appearance as part of intrasexual competition to attract desirable mates.

Hill and Durante (2011) explored how ovulation influences women's mating preferences and behaviours. Their research found that women tend to dress more provocatively and exhibit greater interest in appearance-enhancing behaviours during the ovulatory phase of their menstrual cycle. This suggests that females may strategically invest time in their appearance during peak fertility to attract potential mates.

The significant spending in the beauty and fashion industries also offers strong evidence of mate attraction and selection behaviours.

BEAUTY INDUSTRY

The global beauty industry was valued at approximately $532 billion in 2019, with consumers in the United States alone spending over $80 billion on cosmetics and personal care products in 2020 (Statista).

This industry encompasses various products and services, including skincare, makeup, haircare, fragrances, and spa treatments, catering to both men and women and reflecting a diverse consumer base.

FASHION INDUSTRY

The global fashion industry is valued at over $2.5 trillion, as reported by McKinsey & Company, with consumers in the United States spending approximately $380 billion on apparel and footwear in 2019 (Statista).

This industry encompasses clothing, accessories, footwear, and textiles, spanning a wide range of segments from luxury brands to fast-fashion retailers, catering to different consumer preferences and budgets.

SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE SUPPORTING SEXUAL SELECTION THEORY IN PHYSICAL ATTRACTION

Symmetry signals genetic fitness and resistance to disease (Little et al., 2011; Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999).

A waist-to-hip ratio of 0.7 is linked to female fertility (Singh, 1993, 2002; Zaadstra et al., 1993).

Height in men correlates with reproductive success (Pawlowski et al., 2000; Stulp et al., 2013).

Masculine features signal high testosterone and genetic strength (Johnston et al., 2001; Penton-Voak & Perrett, 2000).

Neonatal features in women indicate high oestrogen levels (Perrett et al., 1998).

Muscularity in men signals physical strength and genetic quality (Frederick & Haselton, 2007).

Penis size may contribute to perceived virility (Dixson et al., 2013).

Clear skin and symmetrical features are universally attractive (Grammer et al., 2003).

This research provides strong empirical evidence that physical attraction is an evolutionary signal of genetic health, fertility, and reproductive success.

CRITIQUES OF SEXUAL SELECTION THEORY APPLIED TO PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS

While sexual selection theory provides a strong evolutionary explanation for physical attraction, it is not without its criticisms. Several challenges arise when applying this framework to human mate preferences:

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL INFLUENCES

One major critique is that cultural and social factors heavily shape perceptions of attractiveness, challenging the idea that preferences are purely evolutionary. For instance:

Historical variations in beauty standards: Fuller-figured women were considered highly attractive in the Renaissance, contrasting with modern preferences for a slimmer figure. This suggests that attractiveness is not entirely biologically fixed.

Media influence: The modern beauty and fashion industries, mainly through advertising and social media, may reinforce and exaggerate specific beauty standards rather than reflect innate preferences.

Research by Swami and Tovée (2005) found that socioeconomic factors influence preferences for body shape. Men from poorer environments prefer larger body sizes, contradicting the universal appeal of a low waist-to-hip ratio.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION

Sexual selection theory assumes a one-size-fits-all model of attraction, often overlooking:

Variability in preferences: Some men may prefer different body shapes, facial features, or ages based on personal experience, culture, or environmental influences.

Same-sex attraction: Much of the research focuses on heterosexual attraction, ignoring mate preferences in same-sex relationships. If attraction were purely driven by reproduction, the existence of stable, long-term same-sex relationships would be difficult to explain within this framework.

OVERSIMPLIFICATION OF PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS

Sexual selection theory tends to oversimplify the role of physical attractiveness, often neglecting the impact of:

Personality and intelligence: While physical attractiveness is important, many prioritise qualities like kindness, humour, and intelligence when selecting a long-term partner. Buss and Barnes (1986) found that in mate selection, personality traits ranked higher than physical appearance for both men and women.

Non-visual factors: Preferences are influenced by voice tone, body language, and scent, which are not accounted for in most physical attractiveness research.

EVOLUTIONARY MISMATCH

Modern environments differ drastically from the ancestral environments in which these mate preferences allegedly evolved:

Contraception and medical advancements: Fertility cues like a youthful appearance may no longer be as crucial, as reproductive success is now controlled by medical technology rather than mate choice.

Shifts in gender roles: In societies where women have financial independence, mate preferences may be shifting. Eagly and Wood (1999) found that as gender equality increases, the importance of physical traits in mate selection decreases, suggesting that evolved preferences are not as rigid as sexual selection theory implies.

LACK OF DIRECT CAUSATION

Many studies show correlations rather than causation when linking attractiveness to reproductive success. Just because men prefer symmetrical faces or a low WHR does not mean these traits enhance survival or reproduction.

For example, Pawlowski et al. (2000) found that while taller men are preferred, height does not always correlate with greater reproductive success in modern populations. Similarly, Buss (1989) found a preference for younger women, but lifestyle choices than age-based fertility cues more influence modern birth rates.

CHEATING EVOLUTION THROUGH PLASTIC SURGERY

One significant challenge to the evolutionary perspective on physical attraction is the ability to "cheat" biological signals through plastic surgery and cosmetic enhancements. If physical traits are meant to signal genetic fitness, youth, and fertility, then modern medical advancements allow individuals to artificially mimic these desirable features without possessing the underlying biological advantages.

Breast implants, lip fillers, and Botox create features associated with youth and fertility but do not enhance reproductive potential.

Liposuction and body sculpting can artificially create a low waist-to-hip ratio, bypassing natural fat distribution patterns.

Facial symmetry can be surgically enhanced, undermining the idea that it naturally signals genetic stability.

Research by Russell et al. (2019) found that men rated surgically enhanced faces as more attractive than natural faces, suggesting that attraction is based more on perceived cues than actual biological fitness.

Additionally, modern cosmetic interventions may distort natural mate selection. If individuals select partners based on artificially enhanced traits, this could reduce the evolutionary pressure that originally shaped these preferences. This suggests that, in an era of widespread cosmetic surgery, sexual selection theory may not function as effectively as it did in ancestral environments.

THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

The matching hypothesis suggests that people are more likely to form and maintain relationships with partners of similar physical attractiveness. Rather than always aiming for the most attractive person, individuals pursue partners within their attractiveness range, often to reduce the likelihood of rejection and ensure a more stable, reciprocal relationship.

HOW IT WORKS

The core idea is that people make realistic choices when selecting a romantic partner. While initial attraction may lead individuals to seek desirable partners, long-term relationships usually balance desirability and attainability. If someone continually aims for a partner who is much more beautiful than they are, they are more likely to experience rejection, leading them to adjust their preferences over time.

. In simple terms, if everyone were rated on a scale from 1 to 10 in terms of attractiveness, the theory suggests that:

A 1 is more likely to date another 1

A 5 is more likely to date another 5

A 10 is more likely to date another 10

This happens because people aim for the most attractive partner they can get but also consider the likelihood of rejection. A 5 might be attracted to a 10, but if they consistently get rejected by people at that level, they will eventually focus on partners within their own range.

CONNECTION TO SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

The matching hypothesis links closely to social exchange theory, which explains relationships in terms of rewards and costs. According to this perspective, individuals seek relationships with the most significant benefits and the lowest risks. Matching in terms of attractiveness provides a balanced exchange where neither partner feels significantly disadvantaged. If one person is much more attractive, there could be an imbalance in perceived power, leading to insecurity or dissatisfaction in the relationship.

People also consider other factors, such as status, personality, and financial stability, when assessing compatibility, but physical attractiveness is often the initial basis for matching. Ultimately, the matching hypothesis reflects a practical approach to relationship formation, where people balance their desires with realistic expectations to form attainable and mutually beneficial relationships.

RESEARCH STUDIES

WALSTER ET AL. (1966) – THE COMPUTER MATCH DANCE STUDY

Walster et al. (1966) conducted the famous Computer Match Dance study to test the matching hypothesis. They recruited 752 student participants, rated on physical attractiveness by four independent judges, to measure their social desirability. Participants were then told they would be matched with a partner based on a questionnaire assessing similarity. However, the pairings were random (except that no man was paired with a taller woman).

During the dance, participants interacted with their assigned partners, and at an intermission, they were asked to evaluate their date. Findings revealed that physical attractiveness was the primary factor influencing enjoyment of the date, regardless of similarity in personality or intelligence. More physically attractive individuals judged their dates more harshly, and those with higher attractiveness levels reported lower satisfaction with their partners—even when they were similarly attractive. The results suggested that people prefer more handsome partners rather than automatically selecting someone of equal attractiveness, contradicting the matching hypothesis.

However, a follow-up study by Walster et al. found that couples were more likely to continue interacting if they were similarly attractive, offering some support for the hypothesis. One limitation noted by Walster was that the four judges only had brief interactions with participants, and longer exposure could have influenced ratings of attractiveness.

WALSTER AND WALSTER (1971) – FOLLOW-UP STUDY

Walster and Walster (1971) conducted a second study to improve ecological validity. This time, participants were allowed to meet beforehand and interact before deciding on a potential partner. The results differed from the original study, as participants expressed the most liking for partners who were similar in physical attractiveness, supporting the matching hypothesis.

MURSTEIN (1972) – PHOTOGRAPH RATING STUDY

Murstein (1972) provided strong empirical support for the matching hypothesis. He collected photographs of 197 real-life couples at various relationship stages (from casual dating to marriage) and had eight independent judges rate the attractiveness of each individual. The judges were unaware of which people were in a relationship together.

Findings showed that partners tended to be similar in attractiveness, supporting the idea that individuals are more likely to choose partners of comparable physical appeal. Murstein also found that self-perceptions and partner perceptions in the first round of the study were unrealistically high, with individuals rating themselves and their partners more positively. These measures were removed in later rounds to avoid biased results.

HUSTON (1973) – FEAR OF REJECTION

Huston (1973) argued that the matching hypothesis is not based on a preference for similarity but rather on a fear of rejection. In his study, participants were shown photographs of potential partners who had already indicated an interest in them. Participants chose the most attractive partner available, suggesting that people prioritise attractiveness over similarity when rejection is not a risk. However, this study lacked ecological validity, as real-life dating does not provide certainty about a partner’s interest in advance.

WHITE (1980) – REAL-LIFE DATING COUPLES

White (1980) conducted a study on 123 dating couples at UCLA, investigating the relationship between attractiveness and relationship satisfaction. The findings showed that partners with similar attractiveness levels reported higher satisfaction and stronger feelings of love, supporting the matching hypothesis.

The study also suggested that relationships function like a marketplace. If an individual has multiple attractive alternatives, they may devalue their current partner if they believe they can do better. However, if a relationship is strong, individuals may remain loyal, valuing their commitment over potential new options.

BROWN (1986) – LEARNED EXPECTATIONS AND THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

KEY ARGUMENT

Brown (1986) supported the matching hypothesis but provided an alternative explanation for why individuals tend to form relationships with partners of similar attractiveness. Rather than choosing partners based on a fear of rejection, he argued that people develop a learned sense of what is "fitting" for them in relationships.

Individuals adjust their expectations based on what they can offer in a relationship. This self-assessment is shaped over time by social experiences, interactions, and feedback from others. Instead of aiming for the most attractive partner possible and fearing rejection, people naturally select partners they believe are realistic choices based on their perceived attractiveness and desirability.

Brown suggested that people internalise social feedback about their attractiveness, influencing their perception of their romantic value. Those who receive consistent validation of their attractiveness tend to have higher expectations for partners. Conversely, individuals who receive less positive social reinforcement may adjust their expectations downward and seek partners they believe they can realistically attract.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

Brown’s theory shifts the explanation away from a simple fear of rejection and towards self-perception and social learning. This explanation aligns with social exchange theory, as individuals subconsciously evaluate their value and seek equitable relationships where they feel desirable and secure. It also accounts for individual differences, as some people may overestimate or underestimate their attractiveness based on subjective self-perception rather than objective reality.

CONCLUSION

Brown’s learned expectations model complements the matching hypothesis by explaining that individuals do not necessarily consciously seek partners of equal attractiveness out of fear of rejection. Instead, they internalise their perceived social desirability over time, leading them to naturally gravitate toward partners of similar attractiveness based on what they believe they can attain in a relationship.

GARCIA AND KHERSONSKY (1996) – PERCEPTIONS OF COUPLES

Garcia and Khersonsky (1996) examined how others perceive matching and non-matching couples. Participants viewed photos of couples who were either similar or different in attractiveness and completed a questionnaire rating their satisfaction, likelihood of breakup, and future marital success.

Findings indicated that:

Couples who were both highly attractive were perceived as more satisfied and more likely to have a successful marriage.

In mismatched couples, the less attractive male was rated more satisfied than the more attractive female.

The more attractive female was seen as less satisfied in non-matching couples.

These results suggest that people perceive equal attractiveness as a positive relationship factor.

SHAW TAYLOR ET AL. (2011) – ONLINE DATING STUDY

Shaw Taylor et al. (2011) investigated the matching hypothesis in online dating interactions. The study measured the attractiveness of 60 males and 60 females and tracked their messaging behaviour.

Results showed that people initially reached out to partners who were significantly more attractive than themselves. However, they were more likely to receive a response if they contacted someone closer to their attractiveness level, suggesting that matching occurs as a result of social dynamics rather than conscious preference.

BERSCHEID AND DION (1974) – EXPECTATIONS OF RELATIONSHIP OUTCOMES

Berscheid and Dion (1974) investigated how people perceive the relationships of couples with different levels of physical attractiveness. They hypothesised that individuals would expect relationships between partners of similar attractiveness to have better long-term outcomes than mismatched couples.

METHODOLOGY

Participants were shown photographs of couples who were either well-matched or discrepant (where one partner was significantly more attractive than the other).

They were then asked to rate the couples on several factors, including:

Relationship satisfaction (how happy they seemed)

Marital stability (how likely they were to stay together)

Parental quality (how good they would be as parents)

FINDINGS:

Equally attractive couples were perceived as happier and more likely to have stable, successful relationships.

Mismatched couples (where one partner was more attractive) were seen as less stable, with participants predicting a higher likelihood of break-up.

The study reinforced the matching hypothesis, suggesting that people assume that similarity in attractiveness leads to better relationship outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS:

These findings suggest that societal expectations about relationships favour equity in attractiveness, which may influence dating choices and partner selection. People may unconsciously seek similarly attractive partners due to social norms and a desire for stability.

BERSCHEID AND WALSTER ET AL. (1974) – REPLICATION OF MATCHING EFFECT

Berscheid and Walster et al. (1974) aimed to replicate and expand on previous findings, further investigating how physical attractiveness influences romantic selection.

METHODOLOGY:

Participants were presented with photographs of individuals of varying attractiveness.

They were asked to select a preferred partner for a romantic relationship.

The study also measured how attractiveness influenced expectations of personality traits, relationship satisfaction, and overall desirability.

FINDINGS

Attractiveness was the most influential factor in partner selection. Participants overwhelmingly chose the most physically attractive individuals as their ideal partners.

However, when asked to predict long-term relationship satisfaction, participants expected similarly attractive couples to have more successful relationships.

More attractive individuals were perceived to have better personalities, reinforcing the "halo effect"—the cognitive bias where people assume that physically attractive individuals have more positive traits.

CONCLUSIONS

This study further reinforced the importance of physical attractiveness in romantic selection, supporting both the matching hypothesis and the social desirability bias in relationships. It suggested that:

People are drawn to the most attractive partners but expect similarly attractive couples to have stronger relationships.

Attractiveness influences perceptions of personality, meaning physical appearance affects more than just romantic desirability.

These findings helped cement the role of physical attractiveness in relationship psychology, highlighting its influence on both partner choice and societal expectations of romantic success.

COYE CHESHIRE ET AL. (2011) – ONLINE DATING AND THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

BACKGROUND

Coye Cheshire and his team at UC Berkeley conducted a large-scale study on online dating to test the validity of the matching hypothesis in a modern digital context. Traditionally, the matching hypothesis suggests that individuals select romantic partners based on similar levels of social worth, which has often been equated with physical attractiveness. However, this research explored whether the hypothesis still holds when tested with real-world online dating data.

METHODOLOGY

The study used large-scale online dating data to examine whether people actively select partners of similar attractiveness or aim for more attractive partners. The research was divided into four key experiments:

EXPERIMENT ONE: Investigated whether an individual's feelings of self-worth correlated with the social desirability of the partners they sought.

EXPERIMENT TWO: Examined whether a person’s physical attractiveness correlated with the attractiveness of the people they contacted.

EXPERIMENT THREE: Looked at the popularity of online dating users (measured by unsolicited messages received) and whether it correlated with their perceptions of their partners’ desirability and popularity.

EXPERIMENT FOUR: Assessed whether more popular users chose and were chosen by partners of similar popularity.

FINDINGS

People frequently aimed higher than their level of attractiveness when initiating contact. Users generally reached out to people more attractive than themselves, challenging the idea that individuals instinctively seek partners of equal attractiveness.

Despite this tendency, responses were more likely from partners of similar attractiveness. This suggests that while people may try to date "out of their league," mutual attraction and reciprocation are still influenced by matching in social desirability.

Different measures of social worth led to varying conclusions. While some findings suggested people sought more attractive partners, the study also found that individuals voluntarily selected partners with similar desirability in other areas, such as intelligence or personality.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

The study challenged the traditional view of the matching hypothesis by showing that people often attempt to date more attractive partners rather than instinctively selecting those of similar attractiveness.

However, the findings partially supported the hypothesis, as individuals were ultimately more likely to match with partners of similar desirability once mutual selection was considered.

This research highlights how modern online dating offers a broader selection of potential partners. This may encourage aspirational dating behaviour, where individuals attempt to connect with those they perceive as more attractive.

CONCLUSION

Coye Cheshire’s study demonstrated that while people initially reach out to more attractive partners, they are more likely to form relationships with those of similar social desirability in the long run. This supports a revised version of the matching hypothesis, where individuals may aim higher but match based on mutual interest and compatibility. The study also underscores the complexity of attraction, showing that factors beyond physical attractiveness—such as personality and self-worth—play a significant role in partner selection.

SUMMARY OF RESEARCH FINDINGS

Early studies (Walster et al., 1966) challenged the matching hypothesis, showing that people prefer the most attractive partner possible.

Later studies (Walster & Walster, 1971; Murstein, 1972; White, 1980) supported the hypothesis, demonstrating that real-life couples tend to be similarly attractive.

Alternative explanations (Huston, 1973; Brown, 1986) suggest that fear of rejection or learned expectations contribute to matching rather than deliberate selection.

Recent studies (Shaw Taylor et al., 2011) indicate that people aim high but match based on realistic social interactions.

These findings highlight the complexity of attraction, with social, psychological, and evolutionary factors all playing a role in relationship formation.

CRITIQUES OF THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

LIMITATIONS OF PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS AS THE MAIN FACTOR

One of the main criticisms of the matching hypothesis is that it places too much emphasis on physical attractiveness as the basis for relationship formation. In reality, relationships are influenced by multiple factors, including personality, intelligence, shared values, and social background. While physical attractiveness may play a role in initial attraction, long-term compatibility often depends on other qualities.

EXCEPTIONS TO THE RULE

There are many examples of relationships where partners do not appear to be evenly matched in attractiveness. It is common to see one partner who is significantly more attractive than the other. This suggests that factors such as wealth, social status, humour, or emotional connection can compensate for differences in physical appeal. Some argue that the matching hypothesis oversimplifies relationship dynamics by assuming attractiveness is the main criterion for partner selection.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL INFLUENCES

The hypothesis assumes that attraction operates relatively universally, but cultural and societal norms can shape relationship choices. Factors like family influence, arranged marriages or financial security may outweigh physical attractiveness in some cultures. Additionally, attractiveness standards differ across cultures and periods, making the concept of "matching" subjective and variable rather than a fixed rule.

THE ROLE OF INDIVIDUAL PREFERENCES

Not everyone values attractiveness to the same extent. Some people prioritise emotional compatibility, intelligence, or shared interests overlooks. The hypothesis assumes people will naturally settle for someone at their attractiveness level, but individual preferences can lead to pairings that do not fit the expected pattern.

CHALLENGES FROM ONLINE DATING

Modern dating challenges the matching hypothesis, primarily through apps and social media. People often pursue partners based on idealised images rather than realistic assessments of attainability. Online dating allows individuals to connect beyond their immediate social circles, increasing opportunities for people of varying attractiveness levels to interact. This can lead to relationships where traditional matching based on looks is less relevant.

POWER IMBALANCES IN RELATIONSHIPS

The hypothesis assumes that partners have equal agency in choosing a mate, but social and economic power dynamics often shape real-world relationships. Sometimes, a less attractive partner may compensate with other resources, such as financial stability or social connections. This contradicts the idea that relationships are purely based on mutual attractiveness.

Social exchange theory suggests that relationships are formed based on a cost-benefit analysis, where individuals weigh the rewards and drawbacks of a potential partner. In this context, women may be more likely to choose less physically attractive men if those men offer higher social status, financial security, or resources that contribute to long-term stability. This aligns with evolutionary theory, which argues that men and women have different reproductive strategies, with women prioritising resource acquisition due to the higher biological investment in offspring.

However, this raises the issue of alpha bias, as the theory assumes women are primarily motivated by a partner’s status while men are driven by physical attractiveness. This reflects a traditional, gendered view of relationships that may not account for modern social dynamics. At the same time, social exchange theory is also beta-biased, as it often assumes relationship formation works similarly for both sexes without fully considering gender-specific preferences. Despite this, evolutionary theory suggests that these patterns may be more relevant to men, as they historically competed for high-status positions to attract mates. This perspective reinforces the idea that attractiveness and status function differently for each gender in mate selection.

LACK OF CONSISTENT EVIDENCE

While some studies support the matching hypothesis, others suggest people do not always pair up based on attractiveness alone. Some findings indicate that individuals are willing to "trade" different qualities, meaning that attractiveness may be balanced against other desirable traits rather than being the sole determining factor in partner selection.