EYE WITNESS TESTIMONY AND RECONTRUCTIVE MEMORY

INTRODUCTION TO EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY

Eyewitness testimony serves as a real-world application of theories on reconstructive memory and schemas, drawing directly from the foundational work of Bartlett and Bransford and Johnson. These theories have shown that memory is not a perfect recording of events but a reconstructive process shaped by prior knowledge, context, and post-event influences. In the context of eyewitness testimony, this means that what witnesses recall is not merely a replay of what they observed but a combination of their perceptions, subsequent experiences, and the cognitive frameworks they use to make sense of the event.

While schemas and reconstructive memory explain how individuals process and retrieve memories, eyewitness testimony also introduces additional complexities, such as the influence of post-event discussions, leading questions, emotional states, and biases. These factors further illustrate how memory is shaped, distorted, or fabricated, underscoring its dynamic and fallible nature.

OTHER FACTORS INFLUENCING LONG-TERM MEMORY

POST-EVENT DISCUSSION

The post-event discussion demonstrates the malleability of memory by showing how new information encountered after an event can merge with the original memory. For example, a witness to a crime may engage in conversations with others, read media reports, or answer interview questions that unintentionally introduce inaccuracies. These external details become interwoven with the original memory, creating what is known as “memory contamination.”

In legal contexts, this phenomenon can have dire consequences. Witnesses who encounter misleading information may recall events differently, misidentify suspects, or even report details that never occurred. This underscores the importance of limiting external influences on witnesses to preserve the integrity of their testimony.

LEADING QUESTIONS

The way questions are phrased during memory retrieval has a profound effect on accuracy. Leading questions that imply a specific answer can introduce distortions by embedding false details into the memory. For instance, asking, “Did the suspect have a red shirt?” might lead a witness to “remember” the shirt as red, even if they never noticed its colour.

In legal settings, poorly constructed questions in police interviews or courtrooms can shape the witness’s memory, leading to inaccuracies that jeopardise justice. Neutral, open-ended questioning is crucial to avoid contaminating eyewitness accounts.

EMOTIONAL STATE AT THE TIME OF THE EVENT

Strong emotions are pivotal in how memories are encoded and later reconstructed. During a traumatic event, fear might narrow attention to a specific detail, such as a weapon, while causing peripheral information, like the environment or other individuals, to be overlooked. Conversely, positive emotions can enhance certain aspects of memory, often leading to an idealised recollection.

Although emotions can enhance the vividness of memories, they also introduce selective biases, influencing what is remembered and how it is recalled. This dual effect complicates the reliability of emotional eyewitness accounts.

CONFIRMATION BIAS

Confirmation bias can distort memory by reinforcing pre-existing beliefs or assumptions. For instance, a witness who believes a suspect looks “shifty” might later recall behaviours that confirm this view, even if those behaviours were benign. This bias skews memory accuracy, as individuals unconsciously prioritise details that align with their expectations while ignoring contradictory evidence.

RUMINATION

Repeatedly revisiting an event, whether through rumination or re-exposure, can reshape the memory over time. A witness who dwells on a specific detail, such as an assailant’s actions, may amplify its importance or distort its accuracy. Similarly, reliving an emotional memory may heighten certain aspects while diminishing others.

IMPLICATIONS FOR EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY

Applying reconstructive memory and schemas to eyewitness testimony reveals a critical truth: memory is not infallible. Instead, it is a dynamic process influenced by cognitive frameworks, external factors, and emotional states. While eyewitness testimony remains a valuable tool in the justice system, its limitations must be acknowledged to mitigate the risk of errors. Understanding these factors allows for a more rigorous evaluation of testimony, ensuring its role in decision-making is balanced with an awareness of its inherent vulnerabilities.

.EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY

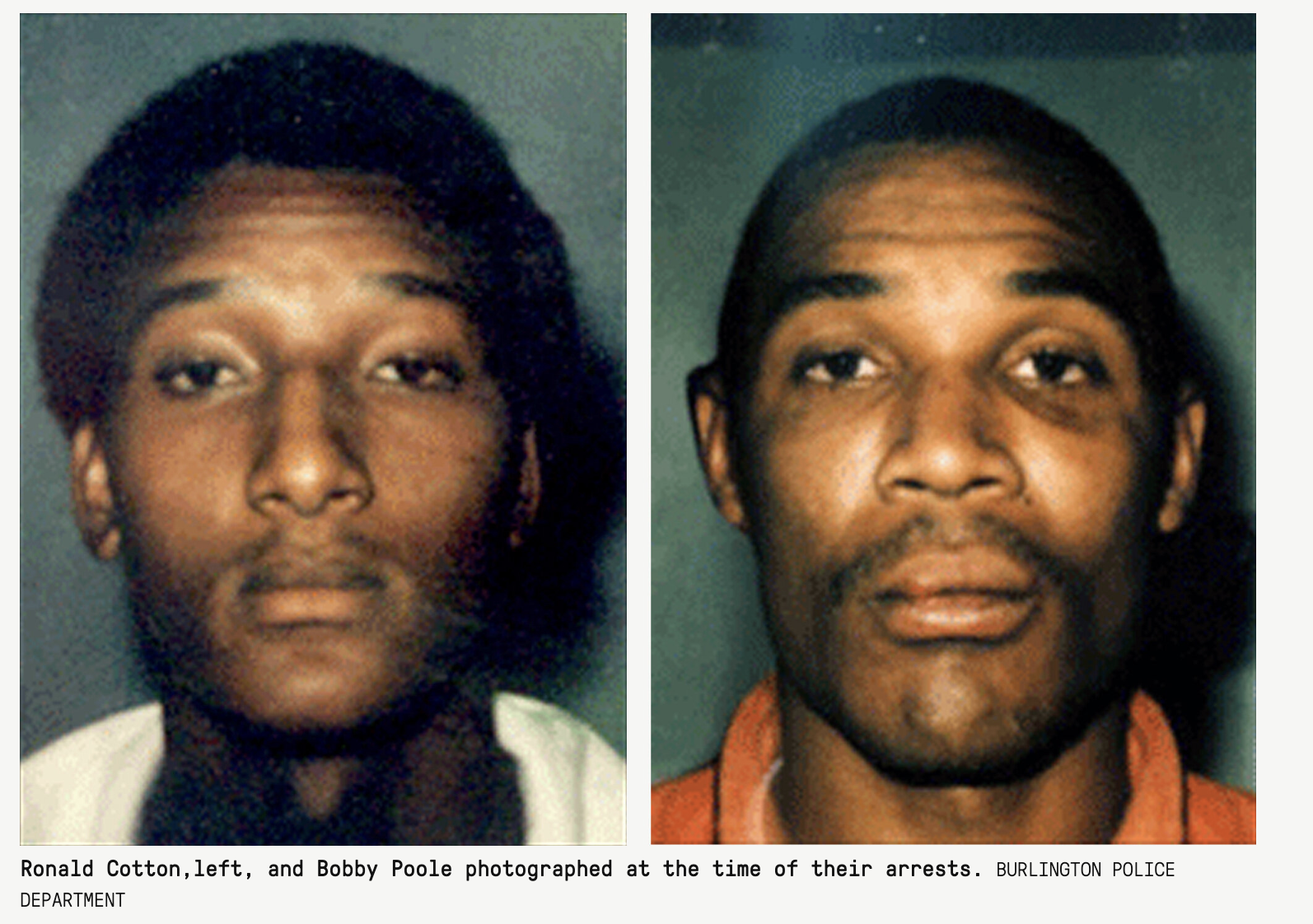

In 1985, a young woman named Jennifer Thompson identified Ronald Cotton, a restaurant worker, in a North Carolina courtroom as the man who had invaded her home and assaulted her at knifepoint the previous year. Thompson’s assured identification was a decisive factor in the jury’s decision to convict Cotton, who received a life sentence plus 50 years. However, while incarcerated, Cotton encountered a man named Bobby Poole, who bore such a striking resemblance to him that they were frequently confused for each other. Poole let slip to another inmate that he was the actual perpetrator of the crime against Thompson. After a decade in prison, Cotton had his conviction overturned when DNA testing confirmed Poole as the assailant.

The man on the left, Ron Cotton, who spent 11 years in prison for the rape of Jennifer Thompson. The man on the right is the rapist. During the assault, Thompson made careful effort to remember her rapist's facial features. Nonetheless she generated a composite and then picked out from a police lineup innocent man. Her memory of the perpetrator's face was changed by these activities without her awareness. She was confident that she was identifying the person who raped her

ELIAZABETH LOFTUS

Elizabeth Loftus is a prominent American cognitive psychologist and expert on human memory, best known for her extensive research on the malleability of human memory and the phenomenon of false memories. Her work has had a profound impact on the fields of psychology, law, and forensic science, particularly in understanding how memories can be influenced by suggestion, misinformation, and misremembering.

Loftus' research has demonstrated that eyewitness testimonies, which are often considered highly reliable in courtrooms, can be surprisingly inaccurate. Through various experiments, she has shown that people's memories of events can be altered by introducing misleading information post-event, a process known as the misinformation effect. This effect has significant implications for the legal system, highlighting the potential for false memories to be created by suggestive questioning, leading to wrongful convictions.

One of her most famous studies involved participants watching footage of a car accident and then answering questions about what they saw. By changing just one word in the questions (e.g., "hit" to "smashed"), Loftus found that participants' recollections of the accident, including the speed of the cars and whether there was broken glass on the scene, could be significantly altered.

Beyond her work on memory suggestibility, Loftus has also explored the phenomenon of false memories, where individuals remember events that never actually happened. Her research in this area has shown that it's possible to implant entirely fabricated memories in some individuals' minds, such as being lost in a shopping mall as a child.

Loftus has faced both acclaim and controversy for her work, especially from those who argue that her findings could be used to discredit genuine victims' testimonies. Despite this, her contributions to psychology have been widely recognized, making her one of the most cited psychologists of the 20th century. Her work continues to influence how legal systems around the world consider and evaluate eyewitness testimonies and memory evidence

FACTORS AFFECTING THE ACCURACY OF EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY:

MISLEADING INFORMATION, INCLUDING LEADING QUESTIONS AND POST-EVENT DISCUSSION; ANXIETY.

Misleading information and leading questions are related concepts often discussed in the context of memory and eyewitness testimony, but they target different aspects of how external inputs can influence recall.

MISLEADING INFORMATION

Misleading information encompasses a broad spectrum of incorrect or deceptive inputs that can significantly influence an individual's recall of events. This term covers phenomena such as schemas, leading questions, the emotional state at the time of memory formation, and post-event discussions. Misleading information can be introduced through various channels, including conversations, media exposure, or documentation that presents inaccuracies about an event. The consequences of misleading information are profound, as it can foster false memories, modify existing recollections, or skew the accuracy of memory recall. Such distortions hold considerable implications in several domains, notably in legal settings where eyewitness testimony can sway judicial decisions and personal and societal contexts where they can shape beliefs and behaviours.

LEADING QUESTIONS

Leading questions are queries that suggest a particular answer or contain information that the questioner is aiming to have confirmed. These questions are phrased to guide the respondent towards a specific response, often by including assumptions or specific details within the question itself. For example, imagine a teacher trying to determine if a student cheated on a test. Instead of asking an open-ended question, the teacher asks, "You copied the answers from your classmate during the test, didn't you?" This question presupposes guilt and leads the student towards admitting to cheating, regardless of whether or not it happened. The way the question is phrased contains an assumption about the student's actions, potentially influencing the student's response and altering their recollection of the event.

RESEARCH MISLEADING QUESTIONS

ELIZABETH LOFTUS AND JOHN PALMER (1974)

These researchers conducted various experiments measuring how leading information affected recall. Forty-five students were shown films of road traffic incidents and then given a questionnaire to describe the accident and answer a series of questions about their observations. One critical question varied between conditions, with one group asking how fast the vehicles were going when they “hit” each other. In contrast, other groups had verbs implying different degrees of a collision, such as “bumped, smashed, contacted, collided”. Results found the words that implied a more vigorous collision resulted in more significant average estimates of speeds from participants. Those exposed to “smashed” gave the highest estimates (41mph), while “contacted” resulted in the lowest speed estimate (30mph), demonstrating how leading questions could influence memory recall.

The experiment was recreated with another group with the verbs “smashed” and “hit”, while a control group was not exposed to such leading questions. They were questioned one week later and asked a series of questions, with one critical question being whether they had witnessed any broken glass. There was no broken glass in the film; however, results found that those who were exposed to the “smashed” condition and thus led to believe the car was travelling faster were more likely to report seeing broken glass, with the control group being the least likely. This highlighted how misleading information post-event can change how information is stored or recalled.

LOFTUS AND ZANNI BROKEN HEADLIGHT EXPERIMENT (1975)

Loftus and Zanni examined the effect of definite articles in questions on memory recall. After viewing a film of a car accident, participants were asked either, "Did you see a broken headlight?" or "Did you see the broken headlight?" The use of "the" implied the existence of a broken headlight, leading more participants to incorrectly report seeing one, highlighting how subtle language cues can create false memories.

LOFTUS (1975) - STOP SIGN EXPERIMENT

Loftus conducted an experiment where participants viewed slides of a car approaching a stop sign, later suggested to some as a yield sign through questioning. The misleading information led participants to misremember the sign they saw, showcasing how suggestive questioning can distort memory.

CESI et al. (1994b) The study by Stephen Ceci involved querying children about everyday events and events that never actually occurred. For example, children were asked to recall a fictional event, such as getting a finger caught in a mousetrap and needing to go to the hospital to remove the trap. They were instructed to think profoundly and attempt to visualise the event periodically over ten-week intervals.

In this research, children were repeatedly asked about events that never occurred, and with each interview, more children began to agree that these false events had happened. Interestingly, even after 11 interview sessions, when the children were informed that some of the events they had described were imagined and did not occur, many persisted in their false statements.

After ten weeks, it was found that approximately half of the children had developed memories of one of the fabricated events, complete with elaboration and detailed descriptions. For instance, some children provided vivid accounts of how their brother attempted to take a blowtorch from them, resulting in a struggle that led to their fingers being caught in a mouse trap. They elaborated on the experience, describing the trip to the hospital with their parents and brother in the family van and the subsequent medical treatment for their injured finger.

This study highlights children's susceptibility to suggestion and the potential for creating false memories through repeated questioning and visualization exercises. It underscores the importance of critically evaluating the reliability of children's memories, mainly when they are influenced by suggestive techniques or misinformation. The study Ceci and his colleagues conducted explored the phenomenon of children's increasing assent to false events over multiple interviews.

NICHOLAS SPANOS et al. (1995) Nicholas Spanos and his colleagues investigated the creation of false memories by leading participants to believe they possessed specific skills based on false information about their infancy. In this study, participants were falsely informed that the hospital in which they were born had placed coloured mobiles over their cribs, which supposedly enhanced their eye movements and visual exploration skills. Half of the participants were hypnotized, while the other half were encouraged to construct mental images of their experiences. The results showed that participants in both groups were highly susceptible to suggestion, with 46% of hypnotized participants and 56% of those encouraged to construct mental images, developing false memories of having well-coordinated eye movements and visual exploration skills due to the coloured mobiles. Furthermore, some participants later "recalled" additional events from their time at the hospital, demonstrating the potential for memory contamination and the creation of false memories through suggestion. This study underscores the ease with which false memories can be implanted, mainly when individuals are provided with suggestive information about their past experiences. It highlights the importance of critically evaluating the reliability of memories, especially those influenced by external suggestions or misinformation.

LOFTUS AND PICKRELL (1995) conducted this study to examine the phenomenon of false memories, specifically how suggestions can create memories of events that never actually occurred. Twenty-four participants aged 18-53 were given narratives of four childhood events. Three of these narratives described actual events that had happened to the subjects as children, as confirmed by a relative. The fourth narrative described a false event—the participant supposedly being lost in a shopping mall at five. This event was plausible but did not happen, which was also confirmed by a relative. Participants were then asked questions on whether they recalled these stories.

Despite the false event never occurring, when the subjects were asked to recall these childhood events, a significant portion of them—29%—reported some memory of the false event. They remembered details such as being lost, crying, being aided by an elderly woman, and eventually reuniting with their family.

This result of 29% of subjects recalling a false memory, compared to the 68% recall of true memories, demonstrates the susceptibility of human memory to suggestion and the creation of false memories. This has profound implications for areas such as eyewitness testimony, where the reliability of memory can be crucial to the outcome of legal proceedings. The study by Loftus and Pickrell is often cited to argue external factors can influence that memory and that confidence in one's memories may not always correspond with their accuracy.

HYMAN ET AL. (1995) Hyman and his colleagues conducted their study on the creation of false memories in 1995” In this study, participants were presented with a list of events from their childhood, including both actual events confirmed by family members and one false event—specifically, being hospitalized overnight for a high fever and possible ear infection.

Participants were interviewed twice, with some time between interviews. During the initial interview, no participants recalled the false event. However, during the second interview, some participants began to recall elements of the false event after exposure to suggestive questioning or other information. Approximately 20% of participants reported remembering something related to the false event during the second interview.

For example, one participant recalled details such as a male doctor, a female nurse, and a friend from church visiting them at the hospital—details that were entirely fabricated as part of the false event. This study demonstrated how suggestion and misinformation can create false memories, even for events that never actually occurred.

SAUL M KASSIN, (1997) A confederate falsely accused students of damaging a computer by pressing the wrong key, took place in 1997. Many students implicated in the false accusation signed confessions, indicating their internalized guilt over the alleged wrongdoing. Some of these students also confabulated additional details related to the false event, further illustrating the impact of suggestive questioning and social pressure on memory recall and fabrication. This study underscores the potential for coerced confessions and the creation of false memories in individuals subjected to suggestive interrogation techniques.

EVALUATION FOR LEADING QUESTIONS

SUGGESTIBILITY AND LEADING QUESTIONS

In situations where the memory of an event is vague, incomplete, or not confidently encoded, suggestibility and the influence of leading questions become significant concerns. Witnesses who were not sure about specific details,, to begin with, are more susceptible to having their memories altered by suggestive questioning. This can lead to the incorporation of false information into their recollections, not because they have "forgotten" the crime but because their initial encoding of the event was not comprehensive or because their memory has been distorted over time.

In summary, while paying attention during a crime might help encode the event into memory, various factors can influence the accuracy and completeness of that memory. This underscores the importance of careful and sensitive interviewing techniques, such as the cognitive interview, designed to minimise suggestibility and aid in retrieving memories.

MISLEADING INFORMATION: POST EVENT DISCUSSION

Post-event discussion refers to the conversations that occur after an event, which can influence and potentially alter individuals' memories. This phenomenon is significant because, during such discussions, people can be exposed to new information, perspectives, or interpretations they did not personally experience. As a result, this additional information can become integrated into their memory of the event, leading to changes in how they recall specific details.

For example, suppose two witnesses discuss their observations after witnessing a crime. In that case, one witness might mention seeing a blue car fleeing the scene, a detail the other witness did not initially notice. This new information might be incorporated into the second witness's memory, leading them to believe they also saw the blue car, even if they did not. This process illustrates how post-event discussions can contribute to creating false memories or alter existing ones, emphasizing the reconstructive nature of memory and its susceptibility to external influences.

How an event is remembered can also be altered or contaminated by repeatedly discussing events with others and/or being questioned.

RESEARCH

SHAW AND GARVAN (1993): In this study, participants witnessed a staged event and then engaged in either a collaborative recall session with other witnesses or an individual recall session. The researchers found that participants who engaged in collaborative recall were more likely to report incorrect details suggested by co-witnesses. This study highlighted the impact of social influence during post-event discussions on memory accuracy.

GARRY et al. (1996): This study examined the impact of post-event discussion on the creation of false memories. Participants viewed a series of slides depicting a fictitious event and then engaged in group discussions. The researchers found that participants were more likely to report false details about the event suggested during the group discussion, even if they had not initially seen those details in the slides. This study demonstrated how post-event debate can lead to the formation of false memories through the incorporation of misinformation from others.

GABBERT ET AL. (2003)

This study by Fiona Gabbert and her colleagues focused on memory conformity following post-event discussion. Participants watched a crime video from different angles and then discussed it. The findings revealed that 71% of participants recalled details they could not have seen, adopting information from the discussion, indicating how leading discussions can alter individual memories.

WRIGHT ET AL. (2000): This study investigated the impact of post-event discussion on eyewitness memory accuracy in a real-world context. Participants witnessed a staged event and then discussed what they had seen with other witnesses. The results showed that participants who engaged in post-event discussions were more likely to incorporate misinformation into their recollections compared to those who did not engage in discussion.

CLARK AND WELLS (2008): This study examined the effects of post-event discussion on eyewitness memory in children. The researchers found that children who engaged in conversation with co-witnesses were more likely to incorporate misinformation into their memories compared to those who did not engage in conversation. Additionally, a dominant co-witness in the discussion further increased the likelihood of memory contamination.

EVALUATION OF POST-EVENT INFORMATION

IS MEMORY FOR POST-EVENT DISCUSSION RELIABLE - CONFLICTING EVIDENCE?

Memon et al. (2006): This study found that post-event discussions may not always lead to memory contamination. In their research, participants watched a crime video and then discussed it with co-witnesses who provided either accurate or inaccurate information about the event. Contrary to expectations, participants exposed to erroneous information during the discussion did not show a significant increase in memory distortion compared to those who received accurate information. This suggests that the impact of post-event discussions on memory recall may depend on various factors, such as the nature of the misinformation and individual differences in susceptibility to suggestion.

Paterson et al. (2019): In this study, researchers investigated the role of social conformity in post-event discussions. Participants witnessed a simulated crime and then discussed it with co-witnesses who provided conflicting information about it. The researchers found that while the misinformation supplied by co-witnesses influenced participants, they could also resist conformity and maintain accurate memories in some cases. This suggests that individuals may not always succumb to social pressure during post-event discussions and may retain accurate memories despite exposure to misinformation.

Wright et al. (2019): This study explored the impact of post-event discussions on children's memory recall. Contrary to expectations, the researchers found that post-event discussions did not always lead to memory distortion in children. In some cases, children could accurately recall details of an event even after engaging in conversations with co-witnesses who provided misleading information. This suggests children may be less susceptible to memory contamination from post-event discussions than previously thought.

ANXIETY AND EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY

Being anxious can significantly affect eyewitness testimony (EWT) through both physical and psychological mechanisms:

Physical Effects

Increased Heart Rate and Blood Pressure: Anxiety triggers the body's fight-or-flight response, leading to elevated heart rate and blood pressure. This can sharpen focus in the short term but may impair the ability to recall details accurately later.

Adrenaline Rush: The adrenaline rush associated with anxiety can enhance memory of the central aspects of an event (due to heightened attention) but detrimentally affect recall of peripheral details.

Sensory Overload: High anxiety can lead to sensory overload, where the brain is bombarded with information. This can make it difficult to focus on specific details, leading to gaps in memory.

Psychological Effects

Narrowed Attention: Anxiety can cause a narrowing of attention, focusing on the source of threat or anxiety. While this might improve memory of certain central details, it often comes at the expense of peripheral details.

Memory Distortion: Anxiety can lead to the distortion of memories. The stress and fear associated with anxiety can alter how memories are encoded, stored, and retrieved, making them less accurate.

Confirmation Bias: Anxious individuals may be more susceptible to confirmation bias, where they are more likely to remember and report details that confirm their anxious feelings or beliefs about the event, potentially ignoring or misremembering conflicting information.

Rumination: Anxious individuals may ruminate over the event, which can alter their memory. Repeatedly thinking about the event can change how it is remembered, often embellishing or diminishing certain aspects of the memory.

RESEARCH ON ANXIETY

THE YERKES DODSON LAW

The Yerkes-Dodson law, formulated by psychologists Robert M. Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson in 1908, describes the relationship between arousal (or stress) and performance. According to this law, performance increases with physiological or mental arousal up to a certain point, after which further arousal decreases performance. In simpler terms, moderate arousal levels can enhance performance, but excessive or insufficient arousal can lead to a decline in performance.

The Yerkes-Dodson curve illustrates this relationship graphically. It typically takes the form of an inverted U-shaped curve, with arousal levels plotted on the x-axis and performance levels plotted on the y-axis. As arousal increases from low to moderate levels, performance also increases. However, beyond the optimal level of arousal, performance begins to decline, eventually reaching a point where it drops below baseline levels.

Here is a description of the key features of the Yerkes-Dodson curve:

Low Arousal: At very low levels of arousal, performance tends to be suboptimal. This is because there is insufficient activation of cognitive or physiological processes necessary for effective task performance.

Moderate Arousal (Optimal Arousal): As arousal increases from low to moderate levels, performance improves. This is the peak of the curve, where individuals are in an optimal state of alertness and arousal, leading to enhanced cognitive functioning and task performance.

High Arousal: Beyond the optimal level of arousal, further increases in arousal lead to a decline in performance. This can be attributed to factors such as increased stress, distraction, or the narrowing of attentional focus, which impede cognitive processes and impair task performance.

Individual Differences: It's important to note that the optimal level of arousal varies between individuals and tasks. Some people may perform best under conditions of high arousal, while others may excel under lower levels of arousal. Additionally, the nature of the task itself can influence the optimal arousal level required for peak performance.

Deffenbacher reviewed 21 studies finding the stress-performance relationship followed an inverted U as proposed by the Yerkes-Dodson Curve. This means that the efficiency of eyewitness testimony depended on the level of stress/anxiety with low and high amounts of anxiety resulting in poorer recall while moderate levels of anxiety yielded the best and most optimum level of recall and performance. The practical application here is that establishing eyewitnesses level of arousal/anxiety may be key in court evidence to determine the validity of their account. However, this in itself is likely to be difficult and purely based on a subjective measure in itself.

CONTRADICTORY FINDINGS

Christianson (1993) et al. found contradicting evidence. When witnesses to real bank robberies were tested on recall, they found that increased anxiety led to improvements in the accuracy of recall. This suggests high levels of anxiety in situations do not always divert attention away from what is happening.

WEAPON FOCUS AND ANXIETY

Weapon focus refers to the phenomenon where individuals focus their attention on a weapon during a criminal act, often at the expense of other details. This concept has been studied extensively in the field of psychology and criminology. When a weapon is present, witnesses or victims may be more likely to remember details about the weapon itself rather than other aspects of the situation or the perpetrator.

Weapon focus and anxiety can interact in several ways:

Enhanced Attention to the Weapon: When individuals experience anxiety in a threatening situation, their attention may become heightened and more narrowly focused on the perceived threat, which in this case could be the weapon. This heightened state of arousal can amplify the weapon focus effect, making individuals more likely to fixate on the weapon and less likely to notice other details in their surroundings.

Impaired Cognitive Processing: Anxiety can impair cognitive processing and memory encoding. When individuals are anxious, their cognitive resources may be diverted toward managing their emotional state, leaving fewer resources available for encoding peripheral details of the event. This can exacerbate the weapon focus effect by reducing the individual's ability to remember aspects of the situation beyond the weapon itself.

Increased Perceived Threat: Anxiety can increase the perceived threat level of a situation. In the presence of a weapon, individuals experiencing anxiety may perceive the situation as more dangerous and therefore focus their attention more intensely on the weapon as a means of assessing the threat and formulating a response. This heightened sense of threat can further exacerbate the weapon focus effect.

Memory Retrieval Interference: Anxiety can interfere with memory retrieval processes. Even if individuals initially encode details of the event, anxiety at the time of recall can disrupt their ability to retrieve those memories accurately. This can lead to difficulties in recalling details beyond the weapon, contributing to the weapon focus effect during testimony or when providing descriptions to law enforcement.

Loftus et al found similar findings when two groups in different conditions observed a violent and non-violent event. In condition 1, a man exited a discussion holding a pen, while in condition 2, I saw a man exiting holding a paper knife covered in blood after a loud altercation. The group who observed the pen were more accurate (49%) than the group observing the violent situation (33%). A possible explanation is the weapon may have distracted their attention from everything else happening and may explain why some witnesses struggle for other details in violent crimes as their focus switches to the weapon itself.

Clifford and Scott found that people who saw a film of a violent attack remembered less than people in a control group who saw a less stressful version. They concluded that witnessing stressful situations in real life will be far more stressful than observing a film and memory accuracy may well be more affected in real life with poorer recall. However, Christianson (1993) et al. found contradicting evidence. When witnesses to real bank robberies were tested on recall, they found increased anxiety led to improvements in the accuracy of recall. This suggests high levels of anxiety in situations do not always divert attention away from what is happening.

Weapon Focus and Cognitive Load (1995, Steblay et al.): This study examined the role of cognitive load on weapon focus. Participants watched a video of a simulated theft, with some asked to memorize a digit while watching. Results indicated that those under cognitive load showed a greater weapon focus effect, suggesting that cognitive resources play a role in determining the extent of weapon focus.

Weapon Focus and Anxiety (2001, Christianson & Hubinette): This study investigated the relationship between anxiety and weapon focus. Results suggested that eyewitnesses with higher levels of anxiety exhibited a stronger weapon focus effect, indicating that anxiety exacerbates the tendency to focus on the weapon rather than other details of the crime scene.

Real-World Applications: Research has also examined the practical implications of weapon focus in forensic investigations. Understanding the dynamics of weapon focus has led to recommendations for law enforcement to minimize distractions during witness interviews, use open-ended questioning techniques, and consider the role of anxiety in eyewitness testimony

EVALUATION OF RESEARCH ON ANXIETY

Due to the ease of replication, other studies have found similar findings showing the findings of Deffenbacher and Loftus are reliable. However, the replicated studies tend to be within artificial settings, which could affect results and lack external validity and wider generalisation to real-world situations, which is again limited.

Yuille & Cutshall’s study contradicts laboratory findings, highlighting the importance of stress in eyewitness testimony. Witnesses to a real-life violent crime such as a gun shooting were found to have remarkable memories of the stressful situation even after observing the gunman be killed. Even those re-interviewed five months later were found to have accurate recall with even misleading questions which were inserted into the questioning having no effect. One thing to note, however, was the witnesses who experienced the most stress were closest to the event, and this may have aided their accurate recall. Therefore, proximity to events itself may be a confounding variable in such research studies. This study illustrated that in instances of real-life stressful situations recall may be accurate even months later. Also, misleading questions, as illustrated, tended to have less of an effect in real-life situations compared to Loftus & Palmer’s laboratory study on misleading questions and stress may be a stronger mitigating factor in recall.

Studies that have subsequently found stress/anxiety to aid recall were likely to have experienced the first increasing levels of stress in the Yerkes-Dodson curve while those suffering from poor recall may be due to them being within the second part with over-arousal resulting in poor recall performance. Such studies involving violence (Loftus/ Clifford) to heighten anxiety levels also raise ethical concerns due to the possible psychological harm they can cause from observing such events. Other research suggests age is also a mitigating factor which could be a confounding variable beyond simply anxiety and this needs to be considered also.

There is also research evidence to suggest the Yerkes-Dodson curve is far too simplified to explain how anxiety affects eyewitness accounts. Fazey & Hardy (1988) proposed Catastrophe theory which may better explain the conflicting findings of how anxiety affects EWT on a 3- dimensional scale. This includes performance, physiological arousal and also cognitive anxiety too. This model proposes that as physiological arousal increases beyond the moderate optimum level, unlike the Yerkes-Dodson curve where there is a steady decline, they observed a drastic drop in performance which they proposed is caused by increased mental anxiety and worry. However, trying to distinguish whether a person felt anxiety or stress in itself would be difficult and subjective.

OVERALL EVALUATION

The weakness here is that such studies are laboratory studies and, therefore, mundane realism and ecological validity.

In real-life scenarios, eyewitnesses to crimes often experience intense emotions such as fear, anxiety, or shock. These emotions can significantly impact the encoding and retrieval of memories related to the event. For example, during a robbery, a witness may be in a state of fear, focusing primarily on the threat rather than details of the perpetrator's appearance. Similarly, a witness to a car accident may feel anxious or distressed, affecting their ability to accurately recall specific details of the event.

Moreover, the motivation and significance attached to the event play a crucial role in eyewitness testimony. In a real crime situation, witnesses understand the gravity of their testimony and the potential consequences it may have on the outcome of legal proceedings. The fear of misidentifying a suspect or providing inaccurate information can heighten the witness's attention and motivation to recall details accurately.

Moreover, in experimental settings where participants watch videos or engage in simulated scenarios, the level of emotional arousal and motivation may not fully mirror that of real-life situations. Participants may lack the same sense of urgency, fear, or personal stake in the outcome, leading to differences in attention, encoding, and retrieval of information.

More interestingly, real-life studies outside the laboratory setting by Yuille and Cutshall have found that witnesses to real events tended to have accurate recall even many months after witnessing events, with misleading questions having little effect, suggesting previous findings by Loftus into leading questions may be limited to laboratory settings. This may be explained due to highly motivated participants displaying demand characteristics that may not indicate real witnesses. In real situations, arousal, stress, anxiety, or concentration may be a stronger factor in recall than leading questions.

FOSTER ET AL, (1995) found supporting evidence for motivation in one study where participants who thought they were watching a real-life robbery and believed their responses would impact an upcoming trial actually be more accurate in their recall.

In 1994, a team of researchers led by Foster and including Libkuman, Schooler, and Loftus embarked on a study to explore how much the perceived importance of identifying someone in a police lineup affects how accurately witnesses can do so. They were curious whether feeling that your identification could really change the outcome of a trial—essentially making a big difference in someone's life—would make people more or less accurate in picking the correct person from a lineup.

To test this, they set up experiments where participants were led to believe either that their identification was crucial (high stakes) or not important at all (low stakes). Surprisingly, the results showed that people who thought their role was critical didn’t necessarily perform any worse than those who believed their identification was of little consequence. This finding challenges the common belief that the added pressure of high stakes might make people less reliable in identifying suspects.

Moreover, the study shed light on the intricate mental processes involved when witnesses are asked to identify someone, especially under different levels of perceived importance. This insight is particularly valuable for the legal system, highlighting the need to consider how eyewitnesses perceive their role and the conditions under which they make identifications.

POPULATION VALIDITY The use of students in the study could introduce confounding variables, potentially limiting the generalisability of the findings. Since students may not represent the full spectrum of ages and backgrounds found in the wider population, the study may lack population validity. Additionally, age has been shown to influence susceptibility to leading questions, with younger individuals generally being more vulnerable to suggestion. Therefore, focusing solely on students may not accurately capture how leading questions affect different age groups, potentially compromising the study's internal validity.

Moreover, the use of questionnaires in data collection presents its own set of challenges. Ambiguities in question wording or response options could lead to participant misunderstandings or misinterpretations, affecting the reliability of the data. Furthermore, researchers' interpretations of participants' responses may introduce bias or misinterpretation, further undermining the study's internal validity.

Critiques of these of lab studies often highlight that the studies are conducted in laboratory environments, where participants, being motivated and eager to participate, may not accurately reflect the demeanor of real-life witnesses. This heightened motivation could serve as a confounding variable, potentially skewing the results. Consequently, the risk of demand characteristics—where participants form an interpretation of the experiment's purpose and subconsciously change their behavior to fit that interpretation—is significantly increased in such controlled settings

On the plus side, experimental studies offer clear advantages in understanding the impact of leading questions and misinformation on memory recall. Unlike field studies, experiments conducted in laboratory settings enable researchers to control for extraneous variables, ensuring a clearer link between leading questions and recall. Additionally, the controlled environment facilitates result verification through replication, establishing reliable outcomes. Furthermore, experimental designs allow for the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships, shedding light on how leading questions influence memory recall—a feat challenging to achieve in real-world settings. Consistent findings across repeat studies bolster the understanding that leading questions and misinformation can indeed affect recall.

ETHICAL CONCERNS: The process of implanting false memories or exposing participants to misleading information raises ethical issues, involving temporary deception of participants, which could have unforeseen psychological impacts.

VARIABILITY IN INDIVIDUAL SUSCEPTIBILITY: There is significant variability in individuals' susceptibility to misleading information. Factors such as age, cognitive abilities, and stress levels can influence the effect of misleading information on memory recall, making it challenging to predict the reliability of eyewitness testimony based solely on the presence of misleading information.

FREUD AND MEMORY

Sigmund Freud, a prominent figure in psychoanalysis, also explored aspects of memory, although his theories differ from contemporary cognitive perspectives. Freud introduced the concept of repressed memories, suggesting that traumatic experiences could be pushed into the unconscious mind as a defence mechanism. According to Freud, these memories could later resurface, impacting an individual's mental health.

Freud's emphasis on the unconscious and the role of early childhood experiences in shaping adult behaviour contributed to his ideas about memory. He proposed that memories could be distorted, suppressed, or repressed, influencing not only individual psychology but also therapeutic approaches.

While Freudian theories have had a significant impact on the field of psychology, it's important to note that many aspects of his work, including the idea of repressed memories, have faced criticism and scepticism. The validity of repressed memories and the potential for false memories to emerge during therapeutic processes are areas of ongoing debate within the psychological community. Contemporary research, influenced by cognitive psychology and neuroscience, has provided alternative explanations for memory phenomena.

FALSE MEMORY SYNDROME: The social epidemic of the 1990s revolved around the phenomenon of recovered memories of childhood abuse, including allegations of satanic rituals. This trend was fueled by the use of suggestion in therapy sessions, where therapists employed special techniques to purportedly bring forward repressed memories. The justification behind this practice was the belief that memories of repeated abuse could be repressed and only unearthed through specialized methods.

However, objections were raised regarding the lack of empirical evidence supporting the idea that memories of such traumatic events could be repressed. Critics pointed out that repetition typically enhances memory rather than suppresses it, and the absence of dissociative disorders associated with repression further undermined the validity of these claims.

A poignant example of false memories influencing legal proceedings is the case of Eileen Franklin, who claimed to have recovered memories of witnessing her father murder her friend, Susan Nason, in 1969. Despite George Franklin's conviction for the crime, subsequent DNA tests proved his innocence. It was revealed that Eileen's memories surfaced through various means, including dreams, hypnosis during therapy sessions (which was initially denied but later admitted), and even while looking at her own daughter.

Many of the details Eileen provided matched newspaper accounts of the incident, suggesting that exposure to external information may have influenced the construction of false memories. This highlights the concept of constructive memory and the potential for memories to be distorted or fabricated, impacting personal identity and legal proceedings alike.

These findings underscore the complexity of memory and the need to critically evaluate the reliability of recollections, especially in cases involving traumatic events and suggestive therapeutic practices. The revelation that memories can be constructed, and sometimes false, raises significant implications for our understanding of personal identity and the reliability of memory as a tool for justice.

IS MEMORY RELIABLE- CONFLICTING EVIDENCE.

To understand the reliability of memory, consider two pivotal studies: Yuille and Cutshall (1986) and Bahrick et al (1975). These studies provide insights into how memory can be reliable, and they offer interesting comparisons to the research by Loftus and Palmer, Neisser and Harsch, Loftus and Pickerell, and Shaw et al.

Study I: Yuille and Cutshall (1986) Aim: To assess if leading questions influence eyewitness memory in a real crime scenario. This mirrors the objective of Loftus & Palmer (1974), but with actual crime witnesses.

Methodology: The study centred around a robbery and shooting at a Vancouver gun shop. Eyewitnesses (21 initially, 13 participated in the study) were interviewed four months post-event. They were asked to recount the incident and answer two leading questions about specific, incorrect details (a broken headlight and a yellow panel on the getaway car).

Findings: Eyewitnesses proved remarkably reliable, recalling many accurate details corroborated by police reports. They generally weren’t swayed by the leading questions, with most either correctly denying the false details or stating they didn’t notice them. Accuracy was rated between 79% and 84%.

Study II: Bahrick et al (1975) Aim: To investigate long-term autobiographical memory reliability, focusing on remembering names and faces from school.

Methodology: The study involved 392 participants, aged 17 to 74, who had graduated from high school between 2 weeks to 57 years prior. They underwent various tests, including free recall of classmates, photo recognition, name recognition, matching tests, and picture cueing.

Findings: The study found high accuracy in memory, with about 90% correctness in identifying names and faces within 15 years of graduation, reducing slightly to 80% for names and 70% for faces after 48 years. However, free recall was less accurate, dropping from 60% after 15 years to 30% after 48 years.

Comparative Analysis Compared to Loftus and Palmer, who focused on memory distortion through leading questions in artificial scenarios, Yuille and Cutshall showed that real-life, emotionally charged events could enhance memory reliability. Similarly, while Neisser and Harsch, Loftus and Pickerell, and Shaw et al highlighted the malleability and fallibility of memory, Bahrick et al demonstrated long-term memory reliability, particularly in recognition tasks, in everyday, autobiographical contexts.

Overall, these studies suggest that while memory can be influenced and distorted, especially in artificial or less emotionally charged contexts, it also has the capacity to be remarkably reliable, particularly in situations with strong emotional impacts or when it involves long-term autobiographical details

When exploring the extent to which memory is reliable, it's crucial to consider evidence supporting its reliability alongside evidence suggesting otherwise. This approach provides a balanced view, particularly in light of abundant research questioning the trustworthiness of eyewitness testimony.

OUTCOMES ON THE LEGAL SYSTEM IN LIGHT OF EWT

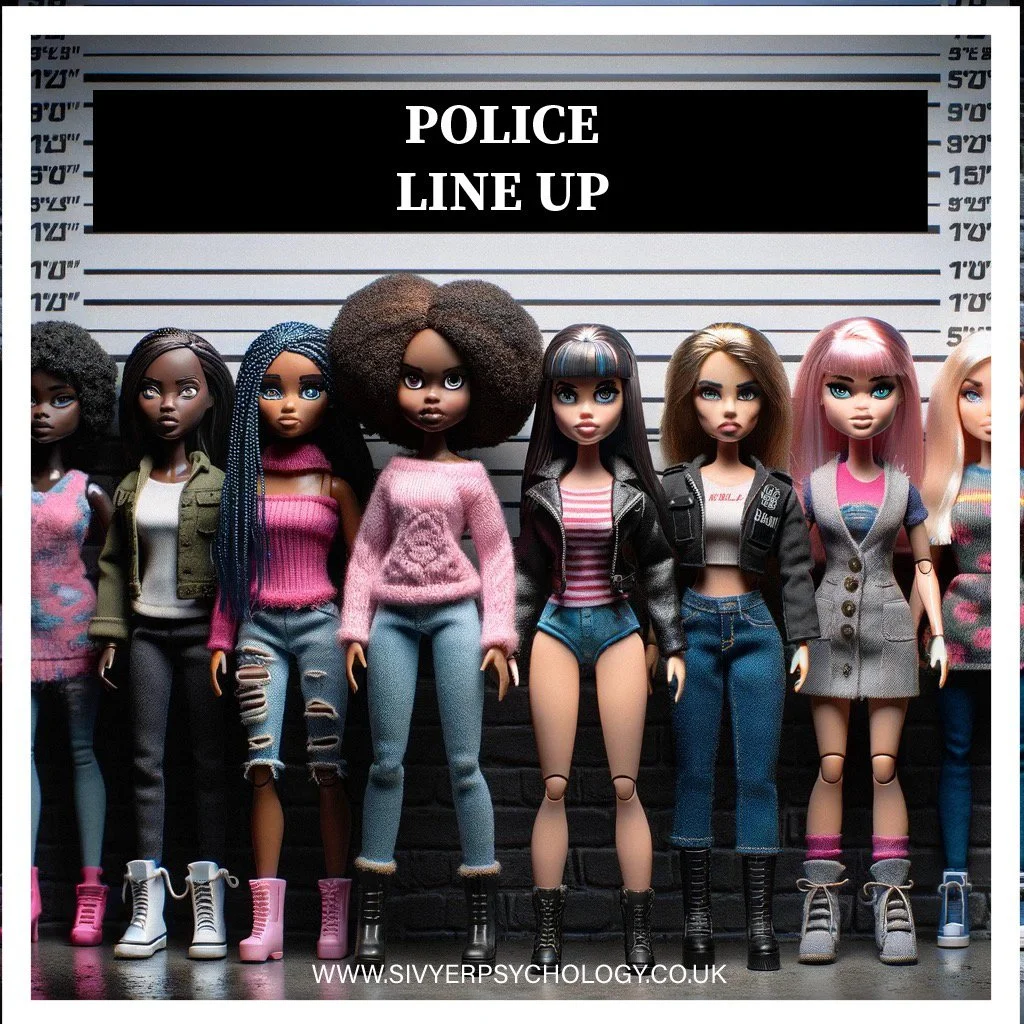

Witness Line-up Adjustments: Studies have shown that witnesses tend to identify suspects based on clothing rather than physical features. To address this, individuals in line-ups are now dressed identically, and their attire is different from the description provided at the crime scene. This approach minimizes the influence of clothing on identification.

Line-up Presentation and Instructions: There's a common presumption that the suspect is included in the line-up, which can skew a witness's choice. To counter this, line-ups are composed of individuals who closely resemble each other. Witnesses are also informed that the suspect might not be present in the line-up. Sequential line-ups, as suggested by Culter & Penrod, where suspects are presented one at a time and a decision is made immediately, have shown improved accuracy in identifications. Additionally, witnesses are not given feedback post-identification to avoid confirmation bias.

Cognitive Interview Technique: In collecting witness statements, a narrative style known as the Cognitive Interview is employed. This method starts with an open-ended question like, "Can you describe what you recall about the night of the incident?" This allows the witness to speak freely with minimal interruptions, reducing the risk of memory distortion through leading questions.

a.Context Reinstatement: Based on Tulving & Thomson's Encoding Specificity Hypothesis (1973), the cognitive interview begins by helping the witness recreate the context of the event. This involves considering the environment, emotional state, and other contextual factors present during the incident to enhance memory recall.

b. Perspective and Order Alteration: The interview includes techniques like changing the perspective (e.g., "What might the bank teller have seen?") and altering the sequence of events (asking to recall events forwards and backwards). These strategies disrupt the influence of pre-existing schemas and help in retrieving more detailed and accurate information.

POSSIBLE EXAM QUESTIONS FOR EYE WITNESS TESTIMONY

Explain how anxiety might affect the accuracy of eyewitness testimony (3 marks)

Describe one research study related to the effect of anxiety on eyewitness testimony (5 marks)

Discuss research on the effect of anxiety on eyewitness testimony (12 marks AS, 16 marks A-level).

Explain what is meant by a ‘leading question’. (3 marks)

Explain how post-event discussion might create inaccuracy in eyewitness testimony (3 marks)

Describe one research study on the effect misleading information has on eyewitness testimony (5 marks)

Outline and evaluate research into how misleading questions affect eyewitness testimony (12 marks AS and 16 marks A-level)