BEHAVIOURAL APPROACH

Learning approaches: the behaviourist approach, including classical conditioning and Pavlov’s research, operant conditioning, types of reinforcement and Skinner’s research

THE BEHAVIOURIST APPROACH - LEARNING THEORY

HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND TERMINOLOGY

Behaviourism emerged in the early 20th century as a reaction against introspection and psychoanalysis. It was pioneered in the United States by John B. Watson, who argued that psychology should be a science of observable behaviour, not unobservable mental states.

In the UK, the term "learning theory" became more commonly used, particularly in applied fields like developmental and educational psychology, to describe specific mechanisms of learning (e.g. attachment formation or phobia acquisition). Over time, "behaviourism" came to represent the theoretical foundation, while "learning theory" referred to its applied models.

CORE ASSUMPTIONS AND PRINCIPLES

BEHAVIOUR IS ENVIRONMENTALLY DETERMINED

Behaviourists adopt a radical environmentalist position, arguing that all behaviour is shaped by experience. The individual is born as a blank slate (tabula rasa), and every action is the product of interaction with the environment. Internal factors such as instincts, genetics, temperament, or biological predisposition are dismissed as irrelevant. This stance reflects strong determinism: behaviour is not chosen, but conditioned by prior exposure to stimuli and reinforcement.

ALL BEHAVIOUR IS LEARNED THROUGH CONDITIONING

Behaviour is acquired through two main types of learning: classical conditioning, which involves forming associations between stimuli and reflexive responses, and operant conditioning, which links voluntary actions to consequences. These processes are automatic, cumulative, and unconscious. Individuals do not think their way into behaviour—they learn it through repetition, reinforcement, and exposure. Complex actions are understood as chains of conditioned responses built up over time.

THE MIND IS A BLACK BOX AND SHOULD BE IGNORED

Behaviourists do not deny that internal mental states exist, but argue they are unobservable, unmeasurable, and scientifically irrelevant. Since thoughts, emotions, and intentions cannot be seen or tested, they are excluded from analysis. The mind is treated as a “black box”: psychology should not concern itself with what happens inside, only with the inputs (stimuli) and outputs (behaviour) that can be objectively recorded.

THE BRAIN IS IRRELEVANT TO PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPLANATION

While modern neuroscience investigates brain structures and processes, behaviourism rejects the brain as a necessary or useful part of psychological theory. The focus is on environmental contingencies, not internal mechanisms. The brain may mediate behaviour, but it does not explain it. For behaviourists, locating behaviour in neural pathways is as pointless as explaining grammar by dissecting the tongue.

PSYCHOLOGY SHOULD BE A PURELY OBJECTIVE SCIENCE

Behaviourism redefined psychology as a natural science, comparable to physics or chemistry. Its goal is the prediction and control of behaviour using empirical methods. Subjective approaches like introspection were rejected for being unverifiable. Instead, behaviourists favoured controlled experiments, measurable outcomes, and falsifiable theories. Even human reasoning is considered irrelevant unless it manifests in observable behaviour. If it cannot be seen, measured, or replicated, it does not belong in science.

LEARNING LAWS ARE UNIVERSAL AND CONTEXT-INDEPENDENT

Behaviourism assumes that the same principles of learning apply across species and settings. Whether conditioning a rat in a lab or a child in a classroom, the same rules of reinforcement and association are believed to operate. Contextual or cultural differences are seen as variations in environmental exposure—not in the underlying mechanisms of learning. The aim is to identify general laws that apply regardless of time, place, or species.

BEHAVIOUR IS PREDICTABLE AND CONTROLLABLE

Behaviourism is not just descriptive—it is interventionist. If behaviour is learned, then it can also be modified. By manipulating the environment—changing the rewards, punishments, and triggers—it is possible to shape future behaviour. This assumption underpins behaviour modification techniques in education, therapy, and even political systems. According to Watson, the ultimate goal of psychology is not understanding but control.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL LEARNING ARE ESSENTIALLY THE SAME

There is no qualitative distinction between human and animal learning. Because behaviour is viewed as a mechanistic, unconscious process, there is no need to invoke human consciousness or reasoning. What applies to a pigeon pecking at a disc applies to a person responding to social cues. Animal studies are not merely useful—they are foundational. The use of rats, dogs, and pigeons in early behaviourist research reflects the belief that their learning processes mirror our own

THERE ARE TWO TYPES OF BEHAVIOURISM

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING (Pavlov)

OPERANT CONDITIONING (Skinner)

KEY FIGURES

Ivan Pavlov: Discovered classical conditioning through his work with dogs.

Edward Thorndike: Proposed the Law of Effect – behaviours followed by satisfying outcomes are more likely to be repeated.

John B. Watson: Founder of behaviourism; emphasised environmental control of behaviour. Famous for the Little Albert experiment.

B.F. Skinner: Developed operant conditioning using Skinner boxes; emphasised reinforcement over punishment.

DIFFERENT SCHOOLS WITHIN BEHAVIOURISM

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

METHODOLOGICAL BEHAVIOURISM

NEOBEHAVIOURISM / PURPOSIVE (TELEOLOGICAL) BEHAVIOURISM

RADICAL BEHAVIOURISM

SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY (NOT STRICTLY BEHAVIOURIST)

SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY IS NOT STRICTLY A BEHAVIOURIST THEORY

Social Learning Theory (Bandura) challenges core behaviourist assumptions by:

Incorporating cognitive processes (e.g. attention, memory, motivation).

Arguing that observation and imitation can lead to learning even without direct reinforcement.

Emphasising vicarious reinforcement (learning through others’ experiences).

Recognising the active role of the learner, rather than seeing them as a passive responder to stimuli.

Thus, while SLT is informed by behaviourism, it is more interactionist and cognitive in orientation.

INTRODUCTION

Behaviourism emerged in the early 20th century as a reaction against earlier psychological approaches that relied heavily on introspection and untestable theories. Structuralism, led by Wilhelm Wundt, focused on breaking consciousness into basic elements through self-report. Functionalism, associated with William James, explored the purpose of mental processes, while Freud’s psychoanalytic theory delved into unconscious drives. To behaviourists, these schools lacked scientific credibility because their methods could not be observed or measured directly.

In contrast, behaviourists—most notably John B. Watson and later B.F. Skinner—argued that psychology should concern itself only with observable behaviour and the environmental stimuli that shape it. They believed true scientific objectivity could only be achieved by studying what organisms do, not what they think or feel. Observation—not introspection—was seen as the cornerstone of science.

In 1913, John Watson published an article entitled Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It, which laid out the foundational assumptions of this new approach:

“Psychology, as the behaviourist views it, is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behaviour. Introspection forms no essential part of its methods, nor is the scientific value of its data dependent upon the readiness to lend themselves to interpretation in terms of consciousness... The behaviour of man, with all of its refinement and complexity, forms only a part of the behaviourist's total scheme of investigation.” — Watson, 1913

Watson wanted psychology to be taken seriously as a science. To achieve this, he aligned it with disciplines such as physics and chemistry, insisting on clear, replicable methods and experimentally testable hypotheses. By using controlled experiments and gathering objective data, Watson believed psychology could deliver reliable, scientific explanations of behaviour. The ultimate goal was to make behaviour predictable, measurable, and subject to empirical verification—just like the natural sciences.

The behaviourists' lack of emphasis on the brain was, in part, a practical necessity. In the early 1900s, no reliable tools existed for investigating brain function. As a result, behaviourists dismissed the study of internal mental processes as speculative and inaccessible. They instead focused on external behaviours that could be measured under controlled conditions.

Behaviourism also built on earlier experimental work. In the 1890s, Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov unintentionally discovered what would later be termed classical conditioning while studying salivation in dogs. Although Pavlov did not conceptualise this as a psychological theory, John Watson adopted his findings to demonstrate that behaviour could be learned through association. Around the same time, Edward Thorndike, working more directly within psychology, developed the Law of Effect—the principle that behaviours followed by satisfying consequences are more likely to be repeated. This idea laid the groundwork for operant conditioning and reinforced behaviourism’s focus on consequences and observable learning.

THE BLACKBOX BLACKBOX PROBLEM

The denial of conscious experience

Behaviourism fundamentally rejects the relevance of internal mental states—such as thoughts, emotions, and intentions—in explaining behaviour. This approach treats the mind as a “black box”: inaccessible, unknowable, and scientifically untestable. B.F. Skinner famously argued that what goes on inside a person’s head is not important for psychology, stating, “What is important is the relation between the behaviour and its consequences.” According to this view, internal processes like memory, attention, and language are by-products of learned associations rather than causes of behaviour. The individual is seen as a passive product of environmental conditioning, with behaviour shaped from infancy by reinforcement histories and external stimuli. Conscious awareness, in this framework, is not dismissed outright but considered irrelevant to scientific analysis because it cannot be directly observed or measured

BEHAVIOUR IS THE RESULT OF STIMULUS-RESPONSE CONDITIONING

Because behaviourists regard internal mental processes as both unobservable and scientifically unreliable, they exclude them from their analysis. Introspection, emotion, and conscious thought are seen as speculative and unnecessary. Instead, behaviourists argue that human and animal behaviour can be fully understood by manipulating external stimuli and observing the resulting responses. From this perspective, the organism is a reactive system: what it has learned is revealed through its behaviour, not its thoughts. All actions, no matter how complex, are viewed as chains of learned associations—stimulus-response pairings formed through conditioning. As John Watson put it, “The goal of psychology is to predict, given the stimulus, what reaction will take place; or, given the reaction, to state what the stimulus is that has caused the reaction.”

THERE IS LITTLE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE LEARNING THAT TAKES PLACE IN HUMANS AND THAT IN OTHER ANIMALS

Behaviourists see no fundamental qualitative difference between human and animal behaviour, since both are viewed as products of stimulus–response conditioning, with internal mental states considered irrelevant. From this perspective, if the 'black box' is ignored, a rat pressing a lever, a lion stalking prey, or a person navigating social life all follow the same basic principles of learning. This assumption underpins the extensive use of animals in behaviourist research. Species such as rats and pigeons became standard subjects, not due to their similarity to humans, but because their environments and behaviours could be easily manipulated and controlled. Comparative psychology thus flourished under behaviourism, with findings from animal studies routinely extrapolated to explain human learning and behavioural patterns

ALL BEHAVIOUR IS LEARNED FROM THE ENVIRONMENT

PEOPLE ARE BORN BLANK SLATES; IT'S ALL NURTURE AND NO NATURE

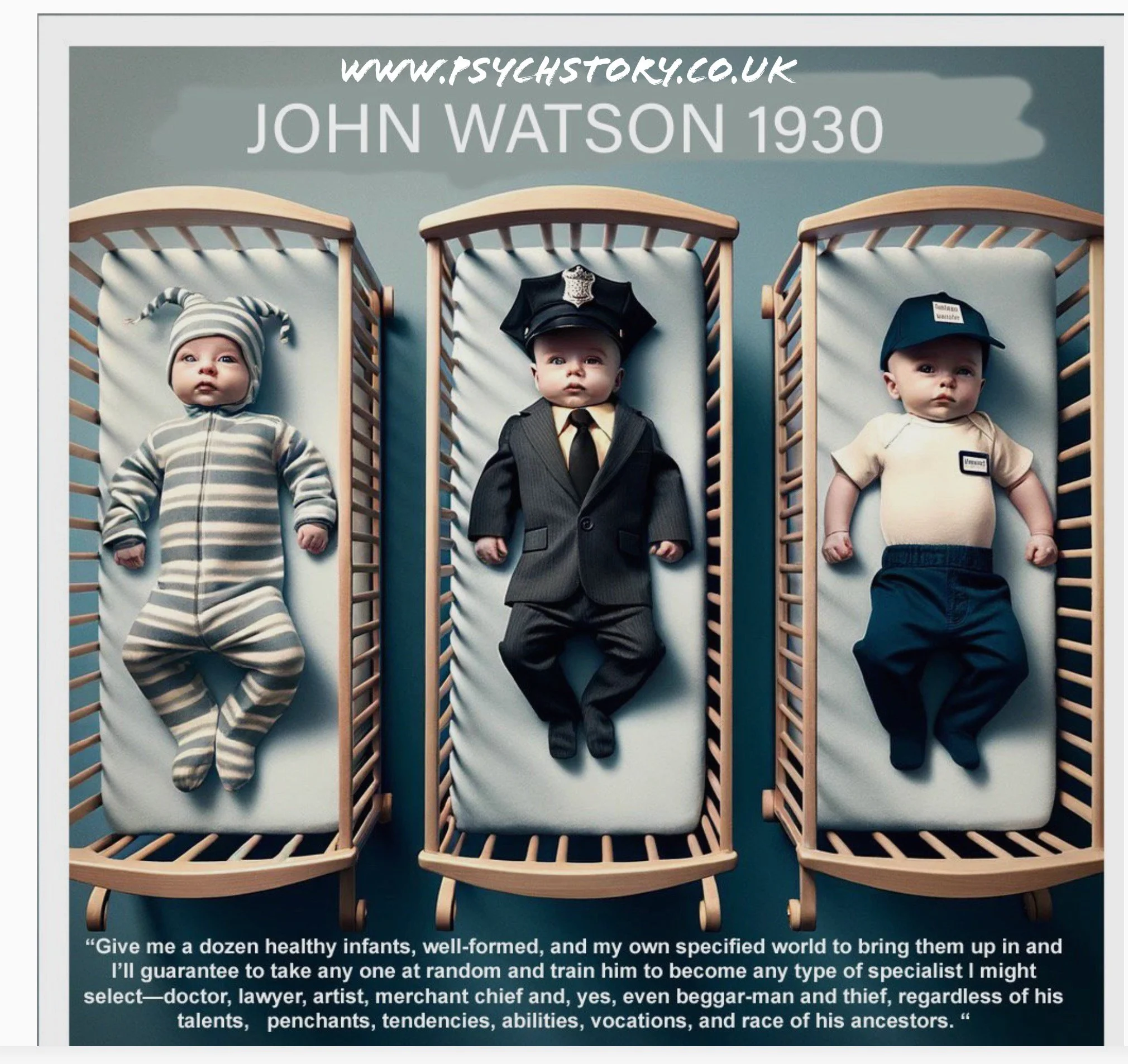

Behaviourists argue that all human behaviour arises from interaction with the environment, not from innate qualities. According to this view, individuals are born as tabula rasa—blank slates—onto which experience writes. Early behaviourists dismissed the influence of biological factors such as genetics, hormones, and evolutionary predispositions, instead asserting that behaviour is wholly shaped by external stimuli and reinforcement histories.

This radical environmentalism is epitomised by John B. Watson’s famous claim:

“Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in, and I’ll guarantee to take anyone at random and train him to become any specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors” (Watson, 1930).

This quote encapsulates the extreme nurture stance that defined early behaviourist thinking, prioritising learning and environment over any role for innate characteristics or inherited traits.

SCHOOLS OF BEHAVIOURISM

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

Ivan Pavlov (1890s)

Although not a behaviourist himself, Pavlov discovered the principles of classical conditioning while studying salivation in dogs. He demonstrated that behaviour could be learned through association between a neutral stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus. His work strongly influenced behaviourist thinking, though he remained focused on physiological reflexes rather than psychology per se.

View on Nature/Nurture: Pavlov did not deny biological predispositions but focused on how reflexes could be modified through learning.

METHODOLOGICAL BEHAVIOURISM

John B. Watson (1913)

Watson rejected introspection and mental states as unscientific, arguing that psychology should only study observable behaviour and environmental stimuli. He adopted Pavlov’s work as proof that all human behaviour is learned. He famously declared that given a dozen infants, he could train any one of them to become anything—emphasising total environmental shaping.

View on Nature/Nurture: Strongly pro-nurture; Watson dismissed genetic or biological influence and believed all behaviour is shaped by the environment.

NEOBEHAVIOURISM / PURPOSIVE (TELEOLOGICAL) BEHAVIOURISM

Clark Hull & Edward C. Tolman (1930s–1950s)

Hull introduced intervening variables (like habit strength and drive) to explain learning mechanisms while retaining a stimulus–response framework.

Tolman proposed purposive behaviourism, suggesting organisms are goal-directed and form internal cognitive maps to navigate environments.

View on Nature/Nurture: Both recognised some biological or cognitive constraints, but saw learning as primarily shaped by experience. Tolman, in particular, acknowledged mental representations.

RADICAL BEHAVIOURISM

B.F. Skinner (1938 onward)

Skinner developed operant conditioning, focusing on how consequences (reinforcements and punishments) shape voluntary behaviour. He rejected introspection but did not deny internal states—instead, he treated thoughts and feelings as behaviours influenced by environmental contingencies.

View on Nature/Nurture: Mainly nurture, but Skinner accepted that innate behaviours exist and that learning depends on prior biological capacities.

SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY (NOT STRICTLY BEHAVIOURIST)

Albert Bandura (1960s onward)

Bandura diverged from traditional behaviourism by incorporating cognition. His theory of observational learning(learning by watching others) included internal processes like attention, retention, and motivation. While influenced by behaviourist ideas, SLT is not considered part of the behaviourist school because it relies on unobservable mental events.

View on Nature/Nurture: Bandura argued for an interactionist model—learning is shaped by both environment and internal (cognitive) processes.

THE TWO TYPES OF BEHAVIOURISM.

There are two types of behaviourism: classical and operant conditioning. Both of these are types of associative learning. i.e., learning that takes place because of conditioning. Learning by association is classical conditioning and learning by consequence is operant conditioning.

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

Classical conditioning is learning through association, a concept discovered by Pavlov, a Russian physiologist. In this form of learning, a conditioned stimulus (CS) becomes linked with an unrelated unconditioned stimulus (US) to produce a behavioural response known as a conditioned response (CR). In simple terms, two stimuli are paired to create a newly learned reaction in a person or animal. Many people know that Pavlov’s 1927 experiment with dogs is a classic example, but it’s essential to understand that classical conditioning involves automatic, reflexive responses rather than voluntary actions. This means that the reactions, such as salivation, nausea, changes in heart rate, pupil dilation or constriction, or even a reflexive motor reaction (like recoiling from a painful stimulus), occur naturally and without conscious control.

Classical conditioning is learning through association, a concept discovered by Pavlov, a Russian physiologist. In this form of learning, a conditioned stimulus (CS) becomes linked with an unrelated unconditioned stimulus (US) to produce a behavioural response known as a conditioned response (CR). In simple terms, two stimuli are paired to create a newly learned reaction in a person or animal. Many people know that Pavlov’s 1927 experiment with dogs is a classic example, but it’s essential to understand that classical conditioning involves automatic, reflexive responses rather than voluntary actions. This means that the reactions, such as salivation, nausea, changes in heart rate, pupil dilation or constriction, or even a reflexive motor reaction (like recoiling from a painful stimulus), occur naturally and without conscious control.

NEUTRAL STIMULUS (NS): A neutral stimulus evokes no reaction. It’s a person, place or thing that has no particular, personal backstory to the individual. Thus, If you don’t smoke, seeing a box of matches might go unnoticed. If you are a puppy and somebody rings a bell, it’s just random noise.

AN UNCONDITIONED STIMULUS (UCS): A stimulus you innately react to, such as seeing food, hearing loud noises, smelling fire, touching heat, seeing vampires, etc.

AN UNCONDITIONED RESPONSE (UCR): A response you innately (naturally) give, such as salivating over food, getting anxious after hearing a loud noise, or cowering when faced with ninjas. This is not conditioned it happens naturally.

A CONDITIONED STIMULUS (CS): A conditioned stimulus evokes a learned reaction to a person, place or thing. The object or concept has a particular, personal backstory to the individual. Thus, If you do smoke, you will notice the box of matches, because you always light your cigarettes with matches. If you are a puppy of Pavlov, then you will notice that bell ring. In other words, the reaction to the previously neutral stimulus has now become conditioned, and the unconditioned response has become conditioned.

A CONDITIONED RESPONSE (CR): Because the object/concept now has a particular, personal backstory to the individual. There will be learned reactions to it. . These are called conditioned responses. For example, as you now smoking, regularly, matches are no longer meaningless. Matches now remind you of a nicotine hit, and you physically need a cigarette. If you are the puppy, you now salivate when you hear a bell as you have learned an association between the bell ringing and food, so you now expect dinner. Or if you get stuck in a lift, the sight of the lift evokes fear because the lift has become a conditioned stimulus and the fear a conditioned response.

KEY STUDY

LITTLE ALBERT BY JOHN B. WATSON AND ROSALIE RAYNER (1920), JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

AIMS : Demonstrate that emotional reactions, specifically fear, can be acquired through classical conditioning.

Test whether pairing a neutral stimulus with an aversive one can produce a learned fear response in a human subject.

DESIGN

A single-case study using a 9-month-old infant (Little Albert) as the participant.

Baseline observations confirmed the absence of initial fear towards the neutral stimulus.

Repeated pairings of a neutral stimulus with an aversive stimulus were implemented to establish conditioning.

METHOD

Initially, Little Albert was exposed to various stimuli (including a white rat) to record his natural reactions, which showed no fear.

The neutral stimulus (white rat) was repeatedly paired with an unconditioned stimulus (a loud, startling noise produced by striking a metal bar).

After several pairings, the infant exhibited a fear response (crying, withdrawal) to the white rat alone.

The conditioned fear response is generalised to other similar stimuli, such as other furry objects.

CONCLUSIONS

The experiment showed that emotional responses like fear can be conditioned in humans, supporting the behaviourist view that emotions are learned through association.

It provided early evidence that learned fear can generalise to similar stimuli, not just the specific conditioned stimulus.

The findings laid the groundwork for further research into classical conditioning and its applications in understanding human behaviour.

Ethically, today’s standards consider the Little Albert experiment highly problematic. In 1920, when the experiment was conducted, ethical guidelines were not as stringent as they are now. Little Albert was subjected to repeated fear conditioning without any debriefing or measures taken to reverse the conditioned fear, which raises concerns about potential long-term harm. Although his parents did give consent at the time, there is little evidence to suggest that they were fully informed about the nature of the experiment or its potential consequences.

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING APPLIED TO DRUG ADDICTION

Classical conditioning plays a significant role in the development and persistence of drug addiction. Dopamine activity in addicts is not limited to the moment of drug consumption. For example, cocaine users exhibit activation of the brain’s reward system not only when taking the drug, but also in response to associated cues—being offered the drug, watching videos of its use, or viewing images such as white powder on a mirror. Similar patterns are observed in smokers and gamblers, whose brains respond to cues like lighters, cigarette packaging, or fruit machines.

According to Claridge and Davis (2003), these findings indicate that environmental stimuli present during drug use become associated with the drug experience through classical conditioning. During early drug use, a range of environmental cues—people, places, objects—are initially neutral stimuli (NS). However, because they are repeatedly present when the drug is taken, they become associated with the unconditioned stimulus (UCS)—the drug itself. The drug naturally produces intense pleasure or euphoria (the unconditioned response, UCR). Over time, the neutral cues become conditioned stimuli (CS) that, even in the absence of the drug, begin to trigger conditioned responses (CR) such as craving, physiological arousal, and drug-seeking behaviour. These learned responses become deeply ingrained and automatic, meaning the addict no longer needs the drug present to feel its pull—the cues alone are enough to provoke relapse.

ADDICTS REACT TO THINGS ASSOCIATED WITH THEIR ADDICTION IN A SIMILAR WAY TO THE ACTUAL ADDICTION ITSELF

In classical conditioning, a stimulus that precedes or co-occurs as a learned stimulus (such as a drug) may become a secondary reinforcer, deriving its influence only by association. Addicts react to things associated with their addiction in a similar way to actual addiction itself.

NEUTRAL A STIMULUS TO CONDITIONED STIMULUS

SMOKING CUES

Matches, Lighters, Cigarette Boxes, Ashtrays: These objects, initially neutral, become associated with the act of smoking. Smokers may experience cravings or a conditioned response when they see or handle these items.

Smoking Buddies: People with whom an individual often smokes become associated with smoking behaviour. Simply being around these friends can trigger cravings or the desire to smoke.

Feeling Stressed Areas: Specific environments or situations where an individual typically smokes, especially when feeling stressed, become powerful cues. Being in these areas can lead to cravings.

GAMBLING CUES

Betting Slips/Shops, Gambling Odds in Newspapers, Casinos: These locations and materials become associated with gambling activities. Seeing a betting slip or being in a casino can trigger the urge to gamble.

Adverts: Advertisements related to gambling, whether on TV, online, or in print, serve as cues. They can lead individuals to think about gambling and may even prompt them to engage in the behaviour.

Playing Cards: Objects like playing cards are associated with gambling games. Handling playing cards can evoke thoughts of gambling and the desire to gamble.

These cues, once they have become conditioned stimuli (CS), have the power to elicit conditioned responses, such as cravings or the urge to engage in addictive behaviours, even when the actual addictive behaviour is not occurring. This phenomenon highlights the role of learned associations and classical conditioning in addiction, where cues in the environment become powerful triggers for addictive behaviours.

OPERANT CONDITIONING

Operant conditioning is a method of learning that occurs through positive and negative reinforcement and punishment of behaviour. Through operant conditioning, an individual associates a particular behaviour and a consequence (Skinner, 1938). While classical conditioning is a form of learning that binds external stimuli to reflexive, involuntary responses, operant conditioning involves voluntary behaviours. It is maintained over time by the consequences that follow those behaviours.

The tools used in operant conditioning are positive and negative reinforcement and positive and negative punishment.

Let’s break them down.

POSITIVE: means to add something, as in mathematics, it means addition, +

NEGATIVE means to minus or withdraw something, as in mathematics, it means subtraction, -

REINFORCEMENT: Means to encourage a behaviour to continue by reinforcing it

PUNISHMENT Means to discourage or stop a behaviour from continuing by punishing it

Individuals change their behaviour in response to rewards and punishments. These rewards (proper name - reinforcement) and punishments can bring mood and material changes (e.g. money).

Reinforcement: when behaviour leads to pleasant consequences, it is more likely to be repeated.

Reinforcement can be positive + and negative) –

The terminology surrounding reinforcement and punishment can be counterintuitive. In behavioural psychology, positiveand negative do not refer to good or bad, but to the addition or removal of a stimulus. Reinforcement—whether positive (adding a reward) or negative (removing an unpleasant stimulus)—increases the likelihood of a behaviour recurring. In contrast, punishment—either by introducing something unpleasant (positive punishment) or taking away something desirable (negative punishment)—aims to reduce or eliminate a behaviour.

If a stimulus is pleasing or rewarding, your psych textbooks might call it "appetitive." If the stimulus is unrewarding or unwanted, it might be called "aversive."Positive reinforcement and negative punishment involve appetitive stimuli. Positive punishment and negative reinforcement involve aversive stimuli.

REINFORCEMENT

Reinforcement in psychology means any consequence that strengthens or increases the likelihood of a behaviour being repeated

POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT –gaining something pleasant increases the behaviour: When behaviour leads to pleasant consequences, it is more likely to be repeated. For example, smoking may give you a cool reputation and get you accepted into certain social groups you see as trendy and desirable. Or it may be winning a tenner on a fruit machine.

NEGATIVE REINFORCEMENT – losing something unpleasant increases the behaviour: When behaviour stops something undesirable, the behaviour is more likely to be repeated. e.g. if a teenager notices that people in the ‘in-crowd” stop ignoring her when she starts smoking, she will be more likely to smoke again. This is what we mean by negative reinforcement. It increases the behaviour because we remove something unpleasant, e.g., being ignored.

Reinforcement can be continuous, e.g. a reward given every time a behaviour happens or intermittent a reward is only given sometimes. Variable ratio schedule rewards are an example of intermittent rewards, such as when you go fishing or gambling. You never know when you are going to hit the big one!

REINFORCEMENT: when behaviour leads to negative consequences, it is less likely to be repeated.

PUNISHMENT: Can be positive + and negative)

PUNISHMENT

Punishment in psychology refers to any consequence that decreases the likelihood of a behaviour being repeated.

POSITIVE PUNISHMENT - when behaviour leads to unpleasant consequences, it is less likely to be repeated. Suppose an individual behaves in an undesirable way. In that case, you present or add an unpleasant thing, such as giving chores, giving lines, phoning parents, smacking, insulting, giving detention, giving fines, giving prison sentences, executing, expelling, suspending, barring, hurting, ignoring, firing. You have made it less likely that the individual will behave that way again. This is called positive punishment.

NEGATIVE PUNISHMENT Losing something pleasant due to engaging in certain behaviours means the behaviour is less likely to be repeated. Suppose an individual behaves in an undesirable way. In that case, a valuable thing can be removed to extinguish the conduct., e.g., taking away confectionery and privileges, removing smartphones, PlayStation, TVs, liberty, toys, sex, affection, etc. You will then have made it less likely that the individual will behave that way again. This is a negative punishment. I used to remove my daughter’s lightbulb if she was naughty!

It’s worth noting that Skinner argued that reinforcement is more effective than punishment in modifying behaviour.

SUMMIN UP

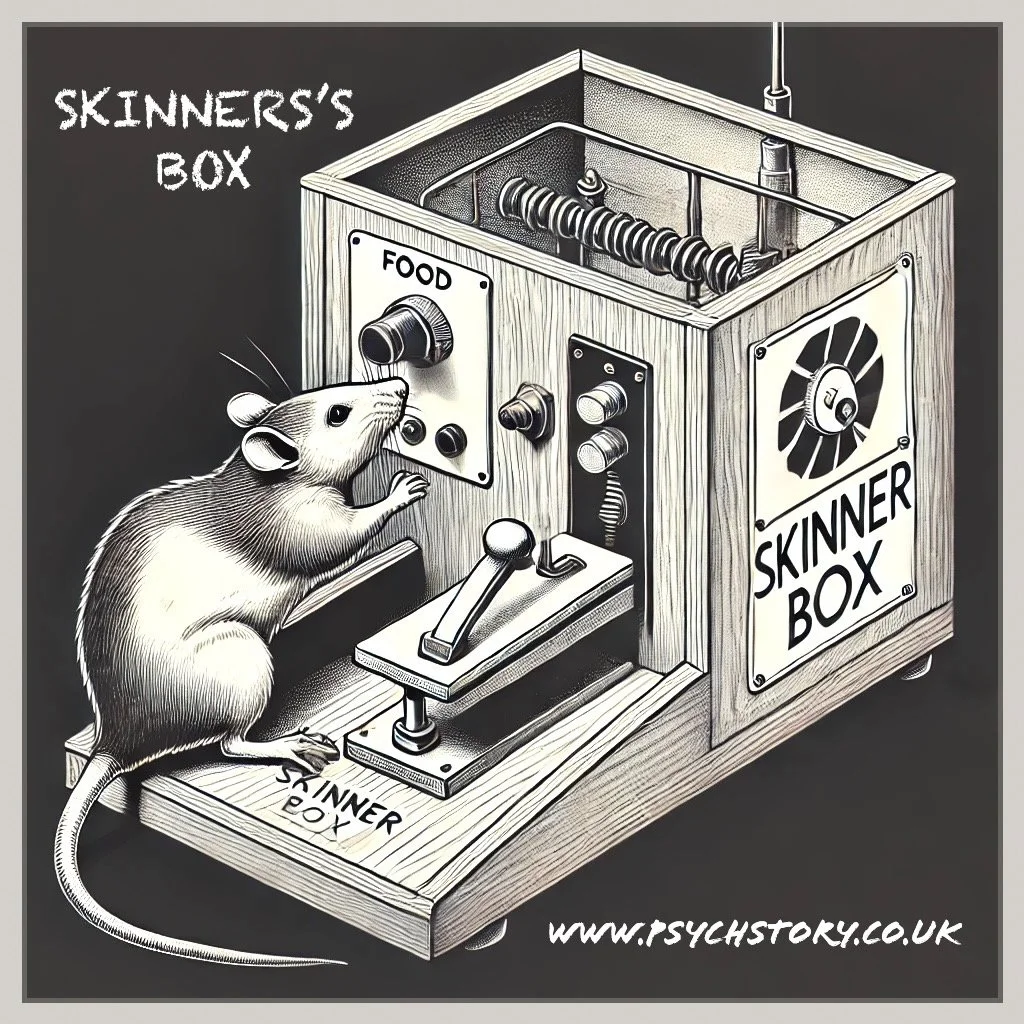

SKINNERS BOX

In one experiment, Skinner placed rats individually into experimental chambers (sometimes referred to as "Skinner boxes") that were designed to deliver food rewards at systematic intervals. He found that by rewarding a rat after it displayed the desired behaviour, he could motivate the rat to increase the frequency of that particular behaviour.

WHAT IT IS AND WHAT IT REVEALED

The Skinner Box (or operant conditioning chamber) was a device created by B.F. Skinner to study how behaviour is shaped by its consequences. It typically contained a lever (for rats) or a pecking disk (for pigeons), which the animal could operate to receive a reward (like a food pellet) or avoid a punishment (such as a mild electric shock). Crucially, the box allowed the environment to be tightly controlled, meaning researchers could manipulate exactly when and how reinforcement occurred.

Skinner used this setup to demonstrate that behaviour is determined by reinforcement, not willpower or conscious choice. He observed that behaviour could be increased, decreased, or extinguished entirely based on the schedule and type of reinforcement used.

But beyond simply proving the principles of operant conditioning, the Skinner Box led to profound discoveries about addiction, compulsion, and behavioural persistence.

SOME OF THE THINGS DISCOVERED USING THE SKINNER BOX

Addiction and self-destructive behaviour: Rats and monkeys would press levers thousands of times to receive doses of cocaine or heroin, even enduring electric shocks to obtain the drug (Bozarth & Wise, 1985). This showed that the brain’s reward system can override survival instincts, laying the groundwork for biological models of addiction.

Stimulation of the brain’s reward centre: Olds & Milner (1954) implanted electrodes into rats’ nucleus accumbens (a key reward area). The rats could self-stimulate by pressing a lever, and many did so repeatedly—ignoring food, rest, and mates—until exhaustion or death. This revealed the sheer power of reinforcement, suggesting that pleasure, not reason, drives behaviour.

Compulsion under variable reinforcement: When pigeons were given food on a variable ratio schedule—rewards delivered after an unpredictable number of pecks—they developed highly persistent behaviour, continuing even when the reward stopped. This is the same schedule used in gambling machines and later, video game mechanics. It demonstrated that unpredictable rewards produce the most addictive behaviours.

Superstitious behaviour: Skinner found that if reinforcement was delivered at regular intervals regardless of the animal’s actions, pigeons would develop irrational routines, like turning in circles or pecking randomly, believing these actions had caused the reward. This suggested that superstition and compulsive rituals could emerge from misattributed reinforcement.

Reinforcement outweighs punishment: In some studies, rats would continue lever-pressing for drug rewards despite being punished with foot shocks, indicating that a powerful reinforcer (e.g. opioids) can override deterrents. This challenged the assumption that punishment is enough to stop harmful behaviour, and helped inform modern addiction treatmen

REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULES IN OPERANT CONDITIONING

Reinforcement schedules in operant conditioning determine when and how often a behaviour is reinforced or rewarded. There are several types of reinforcement schedules, each with its effects on behaviour.

CONTINUOUS REINFORCEMENT

Reinforcement is given every time the behaviour occurs.

Example: A dog is given a treat every time it sits.

Effect: Rapid learning, but behaviour is quickly extinguished when reinforcement stops.

FIXED RATIO (FR)

Reinforcement is given after a set number of responses.

Example: A worker is paid after producing 10 items.

Effect: High rate of response with a pause after each reward.

VARIABLE RATIO (VR)

Reinforcement is given after a varying number of responses, based on an average.

Example: Slot machines pay out after an unpredictable number of plays.

Effect: Very high and persistent responding; highly resistant to extinction.

FIXED INTERVAL (FI)

Reinforcement is given after a fixed amount of time, regardless of how many responses occurred.

Example: Receiving a monthly salary.

Effect: Responses increase as the reward time approaches, creating a “scalloped” pattern.

VARIABLE INTERVAL (VI)

Reinforcement is given after unpredictable time intervals.

Example: Waiting for a fish to bite while fishing.

Effect: Produces slow but steady response rates, resistant to extinction

CRITICAL EVALUATION OF BEHAVIORISM

THE PROBLEM WITH THE BLACKBOX

THE PROBLEM OF EXCLUDING THE MIND

Behaviourism dominated psychology throughout the early twentieth century but began to decline with the rise of cognitive psychology in the 1960s. One significant criticism of behaviourism is its focus on observable behaviour to the exclusion of subjective experiences such as thoughts, feelings, and intentions. Treating the mind as a “black box”—irrelevant and unknowable—behaviourism dismissed internal processes as unscientific, while cognitive psychology insisted that mechanisms like perception, memory, and attention are crucial to understanding behaviour. A well-known joke captures the flaw in behaviourist thinking: two behaviourists spend a passionate night together, and in the morning one asks, “It was good for you—how was it for me?” The humour lies in the absurdity of denying self-awareness, as if humans cannot reflect on their own experience.

To some extent, this exclusion was understandable. When behaviourism emerged, technologies such as fMRI and PET scans did not exist to explore the brain’s inner workings. Yet even as neuroscience advanced, many behaviourists resisted revisiting the mental realm, continuing to treat internal states as irrelevant. Behaviourism viewed individuals as passive responders to environmental stimuli, but cognitive and social learning theories introduced concepts like self-efficacy, mediational processes, and agency—offering explanations for why two people might react differently to the same stimulus. In ignoring the processes between stimulus and response, behaviourism offered a reductive and incomplete view of human action, particularly in domains such as memory, perception, language, and decision-making.

Moreover, the behaviourist insistence on direct observation as a scientific requirement is itself flawed. Observation is not a purely objective act; it is filtered through human interpretation, language, and expectation. Other sciences, such as physics, routinely study entities and forces that cannot be observed directly—gravity, for instance, is inferred through its effects, not seen. Its scientific legitimacy is not questioned simply because it is invisible. This undermines the behaviourist claim that only observable behaviour is valid data.

Paradoxically, however, findings in cognitive neuroscience have, in some respects, vindicated elements of behaviourist thinking. Libet’s famous studies revealed that unconscious brain activity can precede conscious decision-making by up to ten seconds. Neuroimaging allowed researchers to predict participants’ choices before they reported awareness of deciding. This suggests that some human behaviour may be more automatic—and less consciously governed—than cognitive psychology originally assumed. In this sense, behaviourists may have underestimated the mind, but not necessarily the mechanistic nature of decision-making itself.

BEHAVIOURISM AND PARSIMONY

Behaviourism is rooted in parsimony — the idea that the simplest explanation is often the best (also known as Occam’s Razor). Instead of speculating about thoughts, emotions, or unconscious processes, behaviourists argue we should focus only on what we can observe and measure: actions and the external stimuli that cause them.

By reducing behaviour to stimulus-response patterns and using conditioning to explain learning, behaviourism avoids untestable mental concepts. This makes its theories clear, focused, and easy to test in experiments.

However, this strength is also a weakness. Critics argue that behaviourism oversimplifies complex human behaviour. By ignoring internal mental processes like memory, reasoning, and emotion, it misses important parts of the picture—especially when applied to humans rather than animals.

In short: behaviourism offers clarity and scientific rigour, but sometimes at the cost of depth and realism

EXTERNAL VALIDITY

EXTRAPOLATING FROM ANIMALS TO HUMANS

A key criticism of behaviourism is its limited external validity, especially when findings from animal research are extrapolated to human behaviour. Behaviourists often studied rats or pigeons in tightly controlled lab settings, assuming that the same stimulus-response mechanisms would apply to humans. But while a rat may press a lever for food without hesitation, a human faced with a similar reward—say, sweets—may hesitate, worrying about weight gain, social judgement, or long-term health. Unlike animals, humans engage in self-reflection, anticipate future outcomes, and are shaped by language, culture, and complex cognition. This raises doubts about whether findings from non-human animals can truly inform our understanding of human behaviour, rather than simply offering a stripped-down model.

ECOLOGICAL VALIDITY

Even when behaviourist studies involve humans, they are often conducted in highly artificial settings—such as controlled trials using token economies. While these experiments provide precise control over variables, they rarely mirror the complexity of everyday human environments. In real life, behaviour is shaped by unpredictable social interactions, overlapping stimuli, and conflicting motivations. For instance, someone might be praised at work (positive reinforcement) but still feel undervalued due to emotional or relational factors. The sterile nature of lab conditions means that results may lack ecological validity, limiting our ability to generalise findings to naturalistic, day-to-day human behaviour

REDUCTIONISM

Behaviourism has also been criticised for its reductionism—the tendency to explain all behaviour in terms of conditioning while ignoring other influences. Human behaviour is rarely the product of just stimulus and response. Take moral decision-making: a behaviourist might explain honesty as the result of past rewards or punishments. But what about empathy, conscience, or neurological traits like heightened amygdala sensitivity to fear or guilt? By stripping behaviour down to reinforcement histories, behaviourism risks missing the messy interplay between biology, emotion, personal experience, and meaning.

DETERMINISM

Behaviourism has often been criticised for its deterministic stance—a form of environmental determinism that views all behaviours as products of past experiences, thereby ignoring free will. This perspective implies that when something happens, it is not a result of conscious decision-making but of pre-existing conditioning. For example, in Watson and Rayner's Little Albert study, the infant’s fear of a white rat was not a choice but a conditioned response. This deterministic view not only absolves individuals of personal responsibility—since their actions are seen as predetermined by their history—but it also tends to assign blame to the environmental factors that shaped them. In contrast, humanistic psychology asserts that humans possess free will and personal agency, enabling them to make independent choices rather than simply following deterministic laws.

NATURE VERSUS NURTURE

Critics of behaviourism argue that its emphasis on observable learning and environmental influences—focusing on nurture—neglect significant biological factors. Neuroscience has revealed that elements such as chromosomes, neurotransmitters, and hormones profoundly shape our behaviour, suggesting that many actions have an innate, organic basis. Biological psychologists point to factors like biological sex, the effects of drugs, disease, and accidental brain damage—elements that are often overlooked when behaviour is explained solely through conditioning and observable responses. Robert Plomin of King’s College London argues that much of what we consider environmental influence is an expression of genetics. For example, he proposes that a child growing up in squalor might do so because inherited traits, such as a lower IQ, predispose them to that environment rather than the deprivation causing the low IQ.

Over time, the traditional nature versus nurture debate has shifted from a binary opposition to a discussion about proportions. Even Skinner, a radical behaviourist, acknowledged that both genetic and environmental influences are important. Modern research suggests that genetic heritability accounts for roughly 50% of the psychological differences between individuals, with the remaining 50% attributed to environmental factors.

However, this perspective may underestimate the crucial role of learning in early brain development. Human infants are born with relatively few neural networks, and their brains develop rapidly in response to environmental stimuli during critical periods. Missing these key inputs can have lasting, detrimental effects on brain architecture. Thus, while genetics undoubtedly plays a significant role, early learning is essential in shaping who we become

PLASTICITY

Behaviourism remains vital because it is integral to understanding how the brain develops—specifically, how nurture impacts nature. Babies are born prematurely with around 100 billion neurons, but these neurons are not pre-connected. Instead, the brain undergoes significant development through environmental interactions, including developmental and structural plasticity. This is where nature and nurture intersect, as environmental factors shape the growth and organisation of neural connections. Moreover, there is evidence that associative learning—through operant and classical conditioning—creates and enhances neural networks in the brain. These networks undergo structural changes due to environmental influences, practice, and learning new skills. Over time, this neuroplasticity ensures that operant and classical conditioning effects are hardwired into the brain, creating lasting behavioural changes. In this way, the nature versus nurture debate is more of a conundrum solved, as nature and nurture are not separate but inextricably connected; each continually influences and shapes the other, illustrating how they are intertwined in the development of human behaviour.

PRACTICAL APPLICATION IN TRAINING

One of the major contributions of behaviourism is its lasting influence on training and learning techniques through methods such as positive reinforcement and chaining. These principles have been widely applied in both animal and human contexts, demonstrating the practical value of the behaviourist approach. Chaining, for example, involves breaking complex behaviours into smaller, manageable steps that are taught sequentially, with each step serving as a cue for the next. Reinforcement is typically provided only after the final step, and the technique is often taught in reverse (backward chaining) to ensure motivation is maintained through consistent rewards. These structured methods have proven highly effective in areas such as dog training, education, and behavioural therapy, showing that behaviourist principles can be used to teach even intricate behaviour patterns in a clear, goal-directed way.

BEHAVIOUR MODIFICATION AND SOCIAL ORDER

A major contribution of behaviourism is its practical application through behaviour modification—the systematic shaping of behaviour using techniques such as classical and operant conditioning. Central to this approach are principles of reinforcement and punishment, which underpin not only individual learning but also the broader functioning of society. Positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, and punishment are used in diverse settings to encourage or discourage behaviours, from clinical treatment to education and law enforcement. For example, token economies—used in psychiatric hospitals and prisons—reward desirable behaviours with tokens that can be exchanged for privileges, offering a structured system of reinforcement particularly effective for individuals who may struggle with insight or verbal reflection. Similarly, chaining techniques allow complex behaviours to be taught step-by-step, commonly used in animal training, behavioural therapy, and special education.

More broadly, these conditioning strategies form the psychological foundation of societal rules and laws. Without systems of reward and consequence, it is argued that cooperation would collapse, and social order would give way to anarchy. Everyday incentives—such as wages, school grades, legal penalties, and public praise—function as reinforcers to maintain discipline, compliance, and productivity. Behaviourist principles are thus embedded in the very fabric of institutions, shaping behaviour at both individual and collective levels. Contemporary examples include public health campaigns using reinforcement strategies to promote vaccination uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic—such as offering financial incentives or restricting access to venues for the unvaccinated. Likewise, social media platforms and digital advertisers use algorithmic reinforcement to keep users engaged, training behaviour through likes, shares, and targeted content.

However, this powerful influence also invites ethical scrutiny. Behaviour modification can be used not only to promote adaptive behaviours but also to exert social control. Governments, corporations, and institutions often employ behavioural strategies to manage populations, raising concerns about manipulation and autonomy. A stark historical example is the reported use of behaviourist methods on Soviet dissidents, aiming to suppress non-conforming behaviours under the guise of treatment. In modern contexts, behavioural nudging by governments and tech companies has raised questions about consent and transparency. This dual capacity—to enable learning and maintain order, or to enforce conformity and suppress dissent—reveals both the utility and controversy of behaviourist principles in modern life.

BEHAVIOURIST TACTICS IN DATING MANUALS

Behaviourist techniques are frequently repurposed in dating manuals such as The Game, which encourage men to create emotional associations through subtle physical cues. One example is the so-called “tie-touching technique,” in which the man lightly touches his tie while asking a woman, “Tell me something that makes you happy.” The woman’s recall of a pleasant memory produces a positive affective state—an unconditioned response. The simultaneous and seemingly meaningless gesture of touching the tie—formally a neutral stimulus—is repeatedly paired with this emotional state. Over time, the tie-touch becomes a conditioned stimulus, capable of subtly triggering warm feelings directed toward the date. The tactic is based on the assumption that even minor physical gestures can be used to manipulate emotional responses and foster attraction, bypassing critical awareness and treating intimacy as a trainable, controllable outcome

Behaviour modification in A Clockwork Orange

BEHAVIOURISM APPLIED TO ADVERTISING

The advertising industry frequently employs classical conditioning to influence consumer behaviour by creating emotional associations with products. A clear example is the Celebrations chocolate advert, which features a diverse group of people—of all ages, ethnicities, and religions—dancing joyfully in the street to the upbeat song “Celebrate” by Kool & the Gang. The imagery evokes a strong emotional reaction: happiness and a sense of communal joy, which function as unconditioned responses to the stimuli of music, dancing, and social connection. The neutral stimulus—the box of Celebrations chocolates—is repeatedly paired with this atmosphere of euphoria. Over time, this pairing conditions the viewer to associate the product with positive emotions. Eventually, just seeing the Celebrations box can trigger a conditioned response—a feeling of happiness or nostalgia—even outside the advert’s context.

This strategy reflects the behaviourist view of individuals as passive responders to environmental cues. Rather than persuading consumers through reason or product information, advertisers shape preferences through emotional conditioning, turning products into symbols of belonging, joy, or love. In doing so, advertising doesn’t simply reflect what people want—it engineers those desires through carefully crafted associations, reinforcing a culture in which behaviour is subtly shaped by conditioned emotional responses.

According to classical conditioning, if you consistently pair something that naturally evokes positive feelings—like seeing Brad Pitt, who is widely regarded as very handsome—with a Chanel perfume, you begin to associate those positive emotions with the fragrance

BEHAVIOURISM, AND GENDER

Behaviourism treats all individuals as fundamentally equal at birth, shaped entirely by environmental input. In this view, human differences—whether in intelligence, gender, personality, or morality—are not biologically innate but are learned through reinforcement, punishment, and conditioning. This perspective laid the groundwork for social constructionist ideas, which suggest that categories like gender, race, and intelligence are not fixed traits but outcomes of social shaping.

One of the most well-known attempts to apply this thinking was the case of Bruce Reimer, whose penis was accidentally destroyed during a failed circumcision. Under the guidance of psychologist John Money—whose work was rooted in behaviourist principles—Bruce was raised as Brenda, with the belief that gender identity could be conditioned through upbringing. The assumption was simple: if social cues and reinforcement consistently presented the child as a girl, a female gender identity would naturally develop.

However, despite being raised as Brenda, Reimer never identified as female and later reverted to living as a man. The failure of this experiment exposed the limitations of the behaviourist view that all behaviour and identity are environmentally programmed. While conditioning may influence surface-level gender roles, the deeper sense of gender identity may not be fully reducible to learned associations. The case suggests that behaviourism may oversimplify the role of biology in complex human traits

CONCLUSION: THE LEGACY AND LIMITS OF BEHAVIOURISM

Behaviourism remains one of the most influential approaches in psychology—not because it explains everything, but because it explains a great deal with clarity, discipline, and testable logic. It showed that behaviour could be predicted, modified, and replicated through controlled experiments. Conditioning—both classical and operant—clearly plays a powerful role in how humans and animals learn. The methods and principles developed by behaviourists have been used to improve education, therapy, addiction treatment, and behavioural interventions. At the same time, they have been misused in surveillance, social engineering, and manipulative systems of control. Its value is therefore not just in what it explains, but in how it demonstrates the potential—and danger—of applying psychological science to human behaviour.

However, behaviourism is not the full picture. It dismisses internal processes—cognition, language, memory, even the brain itself—as irrelevant. We now know this is overly reductionist. Cognitive functions and biological structures matter. Hormones influence behaviour. Neurons encode learning. Genetics and experience interact constantly. With developments in epigenetics, neuroplasticity, and experience-dependent brain development, psychology is moving toward a more integrated paradigm—one in which nature and nurture are not opposites, but partners. The rigid dichotomy is giving way to models that show how biology is shaped by environment, and vice versa.

Behaviourism’s lasting contribution lies in its demand for scientific discipline in a field once dominated by introspection and speculation. Reasoning may be useful when no tools exist to do better—but you cannot falsify a thought, and you cannot disprove intuition. Behaviourism insisted that claims must be tested, not believed. Its legacy is not just theoretical—it is methodological. It showed that psychology can be a science. What matters now is where we take it next